Every month, a deluge of new books comes flooding out from big publishers, indie houses, and self-publishing platforms. So every month, The A.V. Club narrows down the endless options to five of the books we’re most excited about.

At Night All Blood Is Black by David Diop (translated by Anna Moschovakis, November 10, Farrar, Straus & Giroux)

One could recommend this novella by its name alone. Fortunately, what its evocative and ominous title hints at—a dark story told in lyrical prose—is more than delivered on in David Diop’s rhythmic, enchanting fiction (expertly translated from the French by Anna Moschovakis). At Night All Blood Is Black tells the story of a Senegalese man, Alfa Ndiaye, who fights with the French in World War I. When his best friend, his “more-than-brother,” is fatally injured and begs the narrator to kill him in order to end his suffering, Alfa cannot. The book reads as Alfa’s monologue, delivered from a military hospital, tracing his descent into madness, which includes collecting the severed hands of the enemy soldiers he kills. Diop occasionally finds black humor within the undeniable darkness of the story (at first Alfa’s fellow soldiers find the dismembered hands amusing; it’s only when the narrator cuts off his seventh hand that they grow wary), but more than anything he shows just how slippery the self can be when individuals are placed within extraordinary, violent circumstances.

The Arrest by Jonathan Lethem (November 10, Ecco)

Jonathan Lethem’s latest joins other novels published this year whose plots are incited by a widespread failure in technology. But unlike Don DeLillo’s The Silence or Rumaan Alam’s Leave The World Behind, The Arrest follows the ramifications of the loss of television, the internet, and the world’s other communication systems deeper into its central apocalypse. The catastrophic event at the heart of The Arrest strands everyone in place, making localvores of the population. The protagonist, Hollywood writer Sandy Duplessis, becomes a butcher in Maine, where he’s holed up with his sister, and is soon joined by his old writing partner, who shakes things up in their homestead. Less doomsday speculation than social satire, according to early reviews, The Arrest takes a “kitchen sink” approach to the end of the world, with the Motherless Brooklyn author finding inspiration in everything from ’70s disaster films to ’80s yuppie comedies.

The Office Of Historical Corrections by Danielle Evans (November 10, Riverhead)

Danielle Evans’ debut short story collection, Before You Suffocate Your Own Fool Self, earned the writer a PEN American Prize and a 5 Under 35 designation from the National Book Foundation, among other prestigious honorifics. Ten years later, the writer returns with her second collection, The Office Of Historical Corrections, with stories that center around loss and loneliness and American Blackness, often as an undercurrent to the drama of any given piece. Race comes to the fore in the titular novella, in which a Black historian who works at a federal agency that seeks to correct the historical record is sent to the site of a 1937 lynching in Wisconsin. Lean and precisely crafted, Evans’ stories often interrogate her characters’ charged presents by way of their sorrowful pasts.

Alright, Alright, Alright: The Oral History Of Richard Linklater’s Dazed And Confused by Melissa Maerz (November 17, Harper)

The story of Dazed And Confused has been told before, but never with the depth, breadth, or remarkable reproduction of the film’s conversational rhythms found in Melissa Maerz’s new oral history, Alright, Alright, Alright. (Could there be any other title?) Like Linklater’s depiction of the last day of school circa 1976, Maerz’s book envelops readers in time and place. But while the movie’s more of a snapshot, Alright, Alright, Alright is a panorama, enriched by deep background on the high school experiences and classmates that shaped the film (including the ones who later sued for defamation) and an oral-history-within-the-oral-history about Linklater’s debut feature, Slacker. It’s a class reunion that doesn’t suck, attended by almost all of the living principals, whose stories provide a chance to vicariously attend both the onscreen party at the moon tower and its real-life equivalents at the downtown Austin hotel the cast commandeered for the length of the shoot.

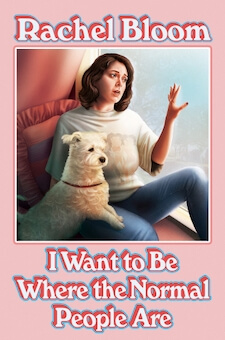

I Want To Be Where The Normal People Are by Rachel Bloom (November 17, Grand Central)

All comedians who “make it” (and even some who don’t) are contractually obligated at some point to write a book of humorous essays, musings, and odds and ends, and up next is Rachel Bloom. After wrapping up her wildly successful musical comedy-drama series, Crazy Ex-Girlfriend, last year and before agreeing to write a film about ’N Sync superfans last week, Bloom wrote I Want To Be Where The Normal People Are, a collection of “hilarious personal essays, poems, and even amusement park maps” on “insecurity, fame, anxiety, and much more.” Included in the collection is an essay, published in The Cut, about how she learned to orgasm and what it’s like to masturbate while pregnant. “When I masturbate, I pretend that she’s somehow gone to a place far far away,” Bloom writes. “Maybe to some sort of magical womb tree along with every other fetus whose mom is currently masturbating. They are safe in the tree, guarded by asexual fairies, until their moms cum, after which point the fetuses are free to reenter the womb.” Suffice it to say, this latest Rachel Bloom project is very Rachel Bloomy.

More in November: To Be A Man by Nicole Krauss (November 3, Harper); White Ivy by Susie Yang (November 3, Simon & Schuster); The Best Of Me by David Sedaris (November 3, Little, Brown); Collected Stories by Shirley Hazzard (November 3, Farrar, Straus & Giroux); Still Life by Zoë Wicomb (November 3, The New Press); Aphasia by Mauro Javier Cárdenas (November 3, Farrar, Straus & Giroux); Bring Me The Head Of Quentin Tarantino by Julián Herbert (November 3, Graywolf); An Onion In My Pocket: My Life With Vegetables by Deborah Madison (November 10, Knopf); Nobody Ever Asked About The Girls: Women, Music, And Fame by Lisa Robinson (November 10, Henry Holt); The Living Is Easy by Dorothy West (November 10, Feminist Press at CUNY); Martha Moody by Susan Stinson (November 10, Small Beer Press); The Care Of Strangers by Ellen Michaelson (November 10, Melville); Kraft by Jonas Lüscher (November 10, Farrar, Straus & Giroux); Prefecture D by Hideo Yokoyama (November 10, MCD x FSG Originals); Answers In The Form Of Questions: A Definitive History And Insider’s Guide To Jeopardy! by Claire McNear (November 10, Twelve); One Night Two Souls Went Walking by Ellen Cooney (November 10, Coffee House); Little Threats by Emily Schultz (November 10, G.P. Putnam’s Sons); The Sun Collective by Charles Baxter (November 17, Pantheon); Nights When Nothing Happened by Simon Han (November 17, Riverhead); The Power Of Adrienne Rich by Hilary Holladay (November 17, Nan A. Talese); Eartheater by Dolores Reyes (November 17, HarperVia); The Orchard by David Hopen (November 17, Ecco); A Promised Land by Barack Obama (November 17, Crown); No Time Like The Future by Michael J. Fox (November 17, Flatiron); The Recognitions by William Gaddis (November 24, NYRB Classics); Ready Player Two by Ernest Cline (November 24, Ballantine); The Freezer Door by Mattilda Bernstein Sycamore (November 24, Semiotexte)

8 Comments

Look, off-topic, or maybe the only topic, but here we are:Biden wins this, *kakow*, Trump is gone. Vamoose, arrivedercei.

Per the Tuskegee Institute, 6 people have ever been lynched in Wisconsin, all of them white. In 1937, 8 people (in the whole U.S) were lynched, all of them black. I don’t know if anyone was lynched in Wisconsin in 1937. The decade as a whole did have a lot more lynchings than the 1950s, which was why I found it somewhat curious that Lovecraft Country was set in the 50s instead of earlier (aside for one flashback). I guessed that perhaps the nadir of American race relations would have been TOO bleak & horrific for Matt Ruff (I admittedly haven’t read his book, only watched the series), which is a bit ironic for a work in the horror genre.

So you came into a list of books set to publish this month, which doesn’t include Lovecraft Country or its author, to make a complaint about how the tv adaptation of that book’s (which you haven’t read) choice of era rubbed you?Just making sure I understand correctly.

I had already looked up the numbers by year last week when I watched the show and wrote up my linked commentary, and recalled that there were also stats by state. So when I read above that “The Office of Historical Corrections” involved a 1937 Wisconsin lynching, I naturally thought to look that up. But, since I did watch the show later than some other people, I was hoping that someone else who watched it and/or read the book would reply with their thoughts.

Have you heard of reply guys? There’s a whole taxonomy of them, but one version is this. The guy who needs to reply to make sure the one minor error that has nothing to do with the actual point receives a lengthy and detailed treatment. Like the stereotype of the nerd who pushes up their glasses while saying “um, actually”. At least this one was sort of interesting.

That description may be the only thing that could interest me in another Letham book at this point. It’s not even set in New York!And yeah, I’ll be all over Alright, Alright, Alright. Also be giving that one as a gift to some friends this year.

I totally thought the Rachel Bloom book was a Judy Bloom book at first glance. Well done, artist/graphic designer.

She’s Judy Blume.