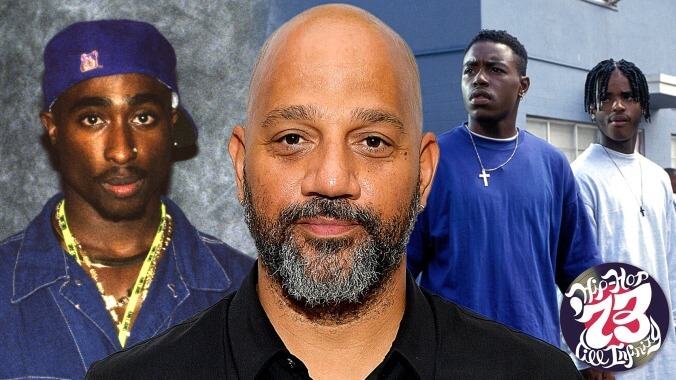

Director Allen Hughes on the power of hip-hop, Menace II Society, and forgiving Tupac

The younger of the Hughes Brothers directing duo discusses how hip-hop changed race relations in America and why Richard Pryor is "my greatest storyteller"

Music Features Menace II Society

This story is part of our new Hip-Hop: ’73 Till Infinity series, a celebration of the genre’s 50th anniversary.

Menace II Society, which celebrated the 30th anniversary of its theatrical release in May, was not the first urban drama to capture the nation’s attention in the late 1980s and 1990s, but it was among the best. On the heels of Colors (1988), Boyz N The Hood (1991), and South Central (1992), Menace II Society staked out turf where those venerable films (and others) dared not tread. It featured an unrelenting bleakness, an uncomfortable reality often referred to as “nihilistic,” according to co-director Allen Hughes. He credits that bleakness, in part, for the film’s success, but “biographical” is the word he prefers, referring to the actual people and places the fictional film represented.

Menace, which premiered to near-universal acclaim at the 1993 Cannes Film Festival, currently comprises a sizable and estimable portion of Allen Hughes’ legacy. His work with the late rapper and poet Tupac Shakur takes up another large slice and not always for the right reason. Allen, along with his brother, Albert, directed Shakur’s first two music videos, Trapped and Brenda’s Got A Baby. But their friendship seemingly ended in 1993 when Shakur was fired during pre-production on Menace II Society and the late rapper retaliated by brutally assaulting Hughes, which landed Shakur in jail for 15 days.

Thirty years later, in what can only be described as a poignant and magnanimous act of forgiveness and attempt at understanding, Hughes has directed Dear Mama, a five-part, Emmy-nominated documentary about Shakur and his mother, the Black Panther activist Afeni Shakur. The. A.V. Club spoke to Allen Hughes about Menace II Society, Tupac Shakur, and the crucial role that hip-hop played in bringing them together.

The A.V. Club: Congratulations on your Emmy nominations for Dear Mama.

ALLEN HUGHES: Oh, thank you. Thank you so much.

AVC: The A.V. Club is celebrating 50 years of hip-hop, it’s the 30th anniversary of your debut film Menace II Society, and you’re also marking the release of your documentary Dear Mama about Afeni and Tupac Shakur. I think I can find a throughline in all of that, but I wonder if you have one of your own.

AH: I’m not sitting in this interview without hip-hop. There is no Menace without hip-hop. There’s clearly no Tupac and Dear Mama without hip-hop. So the throughline is that thing we call hip-hop that has urgency and put punk rock out of business with its voice and its visceral nature. Two young Black boys from Detroit would have never been able to direct a movie at 20 years old without hip-hop being where it was in the culture at the time.

AVC: Talk about growing up with hip-hop as the soundtrack of your life.

AH: Well, it’s interesting because if you weren’t from New York in the early days, there was nothing. It was really ’83, ’84, ’85 when you started feeling hip-hop nationally. Run-DMC and L.L. Cool J were the first to punch through. But Slick Rick and Dougie Fresh, Eric B. & Rakim, the Beastie Boys, this is all stuff we weren’t getting on the West Coast or in the Midwest. So none of us knew about the first 15 years (of hip-hop) because we weren’t in New York.

AVC: There was a lag.

AH: Yeah, I remember from Run-DMC’s debut album all the way to My Adidas … then it very quickly started happening. By the time you get to 1988, just four years later, you’re looking at Straight Outta Compton. That’s light years from My Adidas. And that’s just four short years.

AVC: It seemed to go through a sort of puberty and then it grew up.

AH: When we look at punk rock, it was this little fringe thing that happened in white culture; then hip-hop immediately took over everywhere. Even the white communities back then—it was hip-hop. It wasn’t like white kids caught on later. Back then, 90 percent of the sales of those albums were white kids in suburbia. So I think that coming up in 1984, when we were 12, 13, 14 years old, just seeing what hip-hop did for race relations was the thing that struck me.

AVC: So the Beastie Boys were legit.

AH: Straight up. And what it did for self-possession is what struck me, too. Because you would have this attitude when you went around that you didn’t have before. You felt empowered. You felt like you were seeing representation that just didn’t exist before. It was everything for a young teenager to experience in real-time as it was being born and growing into what it would become.

AVC: As hip-hop made its way into film, it required movies about the community from which hip-hop sprung and about which hip-hop spoke.

AH: You have a whole wave of cinema and television that directly springs out of hip-hop. A whole generation of artists, writers, poets, and actors that would not be here if it weren’t for hip-hop first. So hip-hop as a vehicle has led more (Black and Brown) people to the promised land than any other genre known to history.

AVC: You and your brother Albert were doing music videos at the time, and some interesting stuff at Los Angeles Community College. Did that work connect you to the larger film industry?

AH: Yeah. And keep in mind the films we were making, the two shorts in particular, The Drive-By and Menace II Society [no relation to the feature film] had the DNA of hip-hop. And when we got into music videos, fortunately and unfortunately, we only were able to book hip-hop music videos. To get that big George Michael music video wasn’t going to happen. So it was hip-hop that gave us space to work as professional filmmakers.

AVC: Although the 1991 killing of Latasha Harlins, the Rodney King beating, and the riots after the King trial were still fresh, Menace II Society began with Caine’s (Tyrin Turner) parents’ generation, who lived through the Watts Riots in 1965. Why start there?

AH: I wanted to show what happened when that event decimated that community and what came out of it. The lack of resources and what it does to families and individuals so the audience would get a better understanding of what Caine was born into—hopelessness, basically. The reason why we made Menace was we knew Black people would enjoy the film and be struck by the film, but we were more trying to reach white people, to get them to understand that these children, these boys and girls, are not animals that you see in your evening news.

AVC: That was the narrative in the media. In politics, too.

AH: Yeah, no context. There’s a thing that happens when “someone” makes these decisions in a community, given the lack of opportunity, health care, education, all kinds of shit. And that’s why we wanted to start with Caine’s parents’ generation. What happened in the [Watts] riots was similar to what was going on then. Absurdly, we were witnessing the bookend in real-time with the ’92 riots.

AVC: Normally, you write the script, you shoot the movie, and then you add music later. Hip-hop informed cinema the other way around. The narratives are first told in the music, then comes images in music videos and movies.

AH: Spot on. Probably Ice Cube could sue me for saying this but he virtually ghostwrote Menace II Society. We probably wouldn’t want to make that story if it wasn’t for what was going on with N.W.A. and AmeriKKKa’s Most Wanted. That was influencing us. Because also, keep in mind, Colors had come out a couple of years before.

AVC: In 1988.

AH: And we liked the music in Colors, and it made a lot of money, but it felt fugazi [fake]; it didn’t feel authentic. And then Boyz N The Hood came along but it was another story …

AVC: It’s about Cuba Gooding’s character’s middle-class aspirations.

AH: Yeah. We based Menace on a real guy out of [the L.A. housing project] Jordan Downs. [Menace co-writer] Tyger Williams and I would interview this guy. So as much as I give Cube props for the inspiration, all those narratives in the film were based on a real individual. It’s actually a biography, really, of a kid who was 23 when we were interviewing him. Lifelong gangbanger, crack dealer, and known shooter.

AVC: The thing that separated Menace from Boyz, South Central, and other movies from the era was the depth of the characters. You’re telling me that’s because there’s a real human that you’re referencing there.

AH: Yeah. It’s like with anything; you won’t feel people until you know them. Richard Pryor is my greatest storyteller outside of Mark Twain; with Richard, you see a fully realized junkie, the wino, the prostitute, the cokehead, or pimp, whatever it was, because there was a human being in there that you could feel and touch and know. That’s what Richard did for me and my storytelling.

AVC: Before we talk about Dear Mama, Menace II Society’s ending is bleak. Why go in that direction?

AH: Because we didn’t think it would have any impact if the boys and girls were just going off to college at the end (like Tre in Boyz N The Hood). That film was the studio version. Sony put a lot into that film. (Director) John Singleton put a lot into that film. So that was an elevated version. We wanted ours to be film noir. We wanted ours to be edgy. We wanted ours to be real and hip-hop. And the only way you’re going to wake up the target audience we had in mind, which is the people that don’t live these lives, was to tear it down.

AVC: Anything could happen in Menace and it felt that way.

AH: When we did a test screening I knew we had something because in the front row was a bunch of gang bangers, about five or ten of them, and they were all hugging, crying, just breaking down. I’m like, shit—that’s not even our target audience. But these are the guys that lived that life, and they were crying. So I knew we had something special that would touch people’s hearts and open their minds.

AVC: Tupac was originally cast to play a supporting role in the film. How did that come about?

AH: Because we were friends. But New Line wanted a platinum artist in order to greenlight our film. Tupac wasn’t platinum by that time. But then Juice came out, and he was even better than a platinum artist in New Lines’ eyes—he was a rapper with the lead in a hit movie. So (Tupac) was helping us by attaching himself to Menace so we could get the green light. He did not want to star in the film, nor did we want him to star in the film. He was enamored with John [Singleton] and was starting production on Poetic Justice, and he didn’t want to star in anyone’s films but John. So we’re like, alright, here’s the role of Sharif.

AVC: Why did he leave the project and not play Sharif?

AH: He was starting to become erratic, and we were starting to butt heads. Even before that, he wasn’t being agreeable to anything. So we had to part ways.

AVC: And now 30 years later, you’ve directed, Dear Mama, about Tupac and his mother, Afeni. What led to the development of that series?

AH: I was reluctant to do it but there was a lot of unanswered questions and misunderstandings I had about Tupac. And I thought it would be great to understand him and his journey because I just couldn’t make sense of some of it. I didn’t realize it would be such a cathartic thing for me. I didn’t realize I had not forgiven Tupac. I didn’t realize I hadn’t had compassion for him until I made Dear Mama.

AVC: There have been other other other films about Tupac but this film is about Afeni and Tupac. How did you decide to root the film with his mother?

AH: I was raised by a feminist activist, a woman, a single mom. And I was like, what about the actions and thoughts of the single mother? How does that affect her children, particularly this young Black boy? I thought I would find Tupac through Afeni Shakur and her journey. And she was a mystery. She had all but been erased from history, even by some of her comrades. And boy, did I not realize what a revelation she would be. Anything we love about Tupac came from Afeni. People described them as twins in their intellect, their charisma, their ability to lead. She was also a poet and also went to a performing arts high school like Tupac. When you look at her representing herself in the Panther 21 trial [the 1971 trial and acquittal of 21 Black Panther members for, amongst other charges, conspiring to bomb police stations], and when you hear her words and see her actions, you go wow! This woman is light years ahead of her time, and it’s time we give her her flowers. So I was hoping she would be a revelation, and she was that times 100.

AVC: Afeni was needed to give the community Tupac who would create iconic hip-hop music, which would inform films 20 years later … It all seems very circular.

AH: The thing I love about what you’re saying is that you’re not looking at it and saying what it used to be. You are drawing those threads into modern times. It ain’t mumbo jumbo when you’re celebrating all of it and what it means to us. The themes of it all—the purpose of it all—and how it infused so many things. It’s a very vital conversation, I believe.

1 Comment

“The younger of the Hughes Brothers”? By, like, a couple of minutes maybe. They’re identical twins.