Welcome to Random Roles, wherein we talk to actors about the characters who defined their careers. The catch: They don’t know beforehand what roles we’ll ask them to talk about.

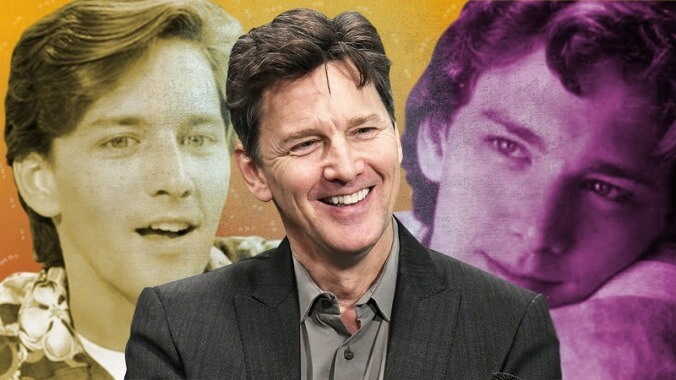

The actor: It can be a bit daunting to meet the movie crush you’ve had for 30 years; there’s a lot of pressure, and what if they disappoint after all that buildup? But no worries if the object of your cinematic affection happens to be Andrew McCarthy, who is somehow as delightful in person as he is onscreen in required teen viewing like Pretty In Pink. After a lifetime in film, in recent years, McCarthy has transformed a passion for travel into a career, penning the 2012 memoir The Longest Way Home: One Man’s Quest For The Courage To Settle Down. He’s also turned his attention to the small screen, directing episodes of dramas like Orange Is The New Black and The Blacklist, as well as starring as a controversial character in last season’s The Family on ABC, where he also directed.

McCarthy visited The A.V. Club while on tour for his new YA novel, Just Fly Away, and by the end of our half-hour interview, the entire office was swooning, confirming the soundness of that particular movie crush choice. There are a few video clips from that interview, but below is the edited transcript, where McCarthy delves into not only his best-known films and his literary career, but also gamely defends Mannequin, Weekend At Bernie’s, and even the Weekend At Bernie’s sequel.

Class (1983)—“Jonathan”

The A.V. Club: Where we are right now in The Onion office is mere blocks away from where your movie career started.

AM: Yeah, my first movie was in Chicago. 1983? I had sex with Jacqueline Bisset at the Water Tower there in a glass elevator. And nothing has ever been the same since.

That part I got because I had just been kicked out of college. I had just gone to college for two years and was asked to leave, because I didn’t go, really. Then a friend of mine called and said, “There’s an ad in the newspaper. They’re having an open call for a movie and wanted 18, vulnerable, and sensitive.” I was like, “Dude.” I went and auditioned with 500 other 18, vulnerable, sensitive kids, and 10 auditions later, I was in the elevator.

AVC: But you met Jacqueline Bisset before being cast?

AM: I did. I was flown out to Los Angeles to go to Jackie’s house and driven up into the canyons where she lived and brought to her living room to be presented to her and pass the Jackie test, which is terrifying.

But when I walked into her house, they said, “Sit down, wait here.” And then I heard the toilet flush, and then she came out. It relaxed me very much to hear the toilet flushing. I knew that, “Okay, she’s human.” Anyway, she was very gracious and lovely to me the whole time, and I was completely in love with her. And she knew it, and she enjoyed that I was completely in love with her, I think.

And I was brand-new to everything. I had never done anything before. It was a bit like winning the lottery.

AVC: Did you and Rob Lowe kind of bond on that movie? Because you were both pretty new?

AM: Yeah, sure. Rob had done a movie before, so he was an old pro, and I was just like, “Huh?” But it was a great experience. And then at the end of it, I kind of felt I’d never, ever do a job again and I’d never work again, so I was very depressed. And I didn’t work for about a year after that. I thought that was my one chance, and I blew it, and it’s all over.

AVC: John Cusack was on that set, too?

AM: He was! It was his first movie, too. Yeah. And Alan Ruck. And Virginia Madsen.

Jackie, basically, was Rob Lowe’s mother, and I had an affair with her and fell in love with her. For the movie. But that’s such a weird movie, because it would never be made now or again.

AVC: She would just be arrested.

AM: It was an R-rated movie, someone just told me yesterday, actually, which seemed odd. It was supposed to be a silly comedy, but then it’s really weird. This isn’t funny. You’re having an affair with your friend’s mother. It’s all very weird and kind of early ’80s kind of bizarre. I haven’t seen it in a million years. I don’t know if it actually would hold up in any way, or if it held up at the time.

I went to see the movie in a Times Square theater just because I had nothing to do. I was unemployed, right? I didn’t have any jobs. So I went to see it. There’s a line in it when Rob finds out, and he says, “You went back even after you knew who she was!” And somebody behind me, being a Time Square audience at the time, yelled, “Yeah! It was good. I’d go back, too. I don’t care whose mother it is.” I’ve remembered that all these years later.

Heaven Help Us (1985)—“Michael Dunn”

St. Elmo’s Fire (1985)—“Kevin Dolenz”

AVC: After that, you found some ensemble parts, like Heaven Help Us.

AM: I think that’s my favorite and/or the best movie I did in that whole era of those movies.

AVC: In St. Elmo’s Fire as Kevin Dolenz, you had all these great, witty lines. You’re smoking. You’re love-struck. You’re lovelorn.

AM: What’s not to like, right?

AVC: You put the cigarette ashes in the stir fry.

AM: That was my finest moment.

AVC: Was that an ad lib?

AM: Yeah! That part, I’d have to say of any of the parts I did, that has the most, sort of, my stamp on. Like, many parts—let’s face it, many people could play them, but that part was very much the way it was because of the way I did that part. It was very much me at the time and the way I felt about the world. That part would have been very different if someone else had played it at the time. Like the bongos and that kind of stupid [stuff]… that was my idea.

AVC: The coffin in the living room?

AM: That was not my idea.

AVC: Did you guys get tight while filming that because you were showing such a close friendship?

AM: No, I was pretty isolated in that movie. I was very much separate. They all lived there in Los Angeles, and I didn’t live there. I lived back in New York, so I was in a hotel. They were all home. I felt very isolated there, which I thought was just fine for the part, too.

The whole Brat Pack thing was this weird thing that just sort of happened. Because then, it was after the publicity for St. Elmo’s Fire, Emilio Estevez was doing an interview, and he had the brilliant idea to go get drunk with a reporter for New York Magazine. They went out with a couple of guys and got drunk with a reporter and behaved like young people do when they’re drunk in a bar. The guy clearly thought these guys were total little brats and wrote that and came up with this very witty name, which we were all appalled and aghast at at the time, and everyone else was thrown into this thing. At the time, it was this sort of, “Oh, my god, what’s this?” And then, as years have gone on, it’s become this iconic, affectionate term to capture that moment in our youth. So now the term is nice. It’s like a wine. The vinegar has turned to wine.

AVC: I think that movie holds up well.

AM: Does it? I haven’t seen it in a million years.

AVC: It captures how isolated people are after college, how lost they feel. And like you said, your character is probably the best example of that.

AM: I just remember doing it and thinking that I was way too young to play—and I was that age—I was 22, but I looked very young. I thought, “I’m not going to be believable as 22.” Because I had only played high school kids until then.

Pretty In Pink (1986)—“Blane”

AVC: Then you had to play a high school kid in your next movie.

AM: Yeah. That was a big thing. “Do I go back to carrying books?” That was a big decision to make.

AVC: That’s the bar? “If I’m carrying books in a movie…”

AM: That’s the bar at that point, yeah. At that point in life, in your career, that’s sort of the bar. It’s like when I heard Arnold Schwarzenegger, or like The Rock, when they’re in a movie and they go, “Well, I’m keeping my shirt on in this film.” I’m like, “That’s the next threshold that you get to. Then you’re an actor. You kept your shirt on, so now you’re an actor. You’re not a bodybuilder.” Anyway, so, I was kind of like that. I kept my shirt on in that film and carried books.

I had actually got the part in Pretty In Pink because I had just been in St. Elmo’s Fire, and then they said, “Well, this part, the part in Pretty In Pink, we’re shooting for this, like, hunky, you know, square-jawed quarterback type.” And I was young and sensitive. So, they said, “Well, you’re not really right for it, but you’ve just been in this St. Elmo’s film. You can audition. We’ll give you a courtesy audition.” So, I went and auditioned, and Molly was there reading with people. When I left, Molly said, “Now that’s the kind of guy. He’s all like pouty and dreamy that I’d fall for.” And John Hughes was like, “That wimp?” But he listened to her, and there I was.

AVC: Well, John Hughes did have kind of a jock complex.

AM: Totally, yeah. That’s what I was supposed to be.

AVC: You’ve said that if you—god forbid—drop dead tomorrow, you’d be remembered as Pretty In Pink actor Andrew McCarthy.

AM: That movie—whatever thing that captured, that will always be my thing that I carry around. Which is fine. It really did touch something for a generation of people, which I was shocked at. I thought at the time, “This is a movie about a girl making a dress and wanting to go to a dance. I mean, does this really have merit?” And it did. That’s what John Hughes did well. He took young people seriously, and their problems mattered, and their thoughts mattered, and the urgency of their things really mattered, and I don’t know that movies—those kind of movies—did that much before that.

So it taps into that moment when we’re all just waking up in life. And then, so you latch onto that and forever hold onto it, because we all have this wistful recollection of those moments when we were coming of age. We are yearning for this past that never was in a very certain way. And I represent that to a lot of people. Often they come up to me, and they’re always disappointed when a) disappointed that I’ve aged, and b) disappointed that it really has nothing to do with me. It has to do with them, and they’re projecting onto me this recollection of their youth. “You don’t understand what it was—” I’m like, “I understand, but it’s not me. You’re responding to your own youth in a very real way.”

AVC: It must be a weird thing to walk around with.

AM: It’s a lovely thing, actually. I’m happy to be the talisman for that.

AVC: What did you think about reshooting the ending?

AM: In the original end, she ended up with Jon Cryer, and my guy just sort of ditched her, and that was the end of it. And then the audience loved the movie until it got to there, and they were the test screening of 30 people in Orange County who decide the fate of movies [and they] decided, “Oh, my god, that can’t be.” So they decided to reshoot it where I come back and I say, “I love you,” and whatever it is I say. I was in New York at the time doing a play, and my head was shaved, and so I had to wear a wig. And the wig they got me was so bad and cheap because I think they thought the movie was just going to be a bomb and be gone in a week. I’ve always said that if they’d known we’d still be talking about it 30 years later, they’d have paid for a better wig. So it’s wig-acting basically at the end. I look so forlorn and sad with this really bad wig on while I’m telling her I love her. That wig does 90 percent of the work for me, because I just look… “Something is wrong with him. Look, it looks horrible.” And it’s just bad wig-acting.

Fresh Horses (1988)—“Matt Larkin”

AVC: You teamed up with Molly Ringwald again for Fresh Horses.

AM: Sure, I mean, I know that it worked. Then that movie came up, and I thought it was interesting. I suppose back then also there was no real great plan afoot. There was no, you know, the hands were not on the wheel. I was just a young guy doing the next job that came along in very real ways. I didn’t have the wherewithal or the savvy to plot and buy material and plan… I just didn’t come from that. It didn’t really even occur to me in a real way. So that job came up, and I’m thinking, “Oh, Molly. I like Molly. And we did well in the last movie. Sure.” I mean, it didn’t work out at all, that one.

AVC: Ben Stiller played your best friend.

AM: Ben was very funny. My memory of Ben is him doing these fantastic Tom Cruise imitations: “Wow, that’s really disturbing and good.”

AVC: That was going to kick off his whole career.

AM: There you go.

Weekend At Bernie’s (1989)—“Larry Wilson”

Weekend At Bernie’s II (1993)—“Larry Wilson”

AVC: One of the questions we received for you on Facebook: “What do two guys do if they find their boss dead?”

AM: Well, the only thing you can do is have a party, yeah. Of course. I mean, that movie was completely stupid and fantastic. It’s the stupidest movie. I love it. I love Bernie’s. My son—he’s 15—he saw Weekend. He’s never seen anything I’ve been in, my kids, but he saw Weekend At Bernie’s, and he said, “Dad, that movie is really stupid.” But I love Bernie. I think Bernie is great. I mean, it was ridiculous. We knew at the time it was ridiculous, and there was no top to go over. You can just do anything. Like, “Let’s just throw him over the rail.” “Yeah, yeah. Let’s throw him over the rail.” “What if the tide washes him out to sea?” “Yeah, let’s do that. Let’s do that. Have him wash out to sea.” You could just do anything with him. And Terry [Kiser, who played Bernie] was great. That was a lot of fun to do, which is not always the case, because often when you’re doing a comedy, it becomes an inside joke where we think it’s really funny, but to other people it’s just not that funny. But that movie has its own logic, and it’s itself.

AVC: On a percentage basis, how much was like a model of the dead guy, and how much was the actor pretending to be dead? How much did he actually have to be in?

AM: It was largely Terry. There was only a dummy when we were dragging him behind the boat. “Serpentine! Serpentine!” But pretty much everything else was Terry or a stuntman, because he fell somewhere and broke some ribs, and so he was on some kind of heavy medication there for a while, so he was really Bernie’d up. But we had a stuntman who was very good do some of it, but very little of it was a dummy. It was just, like, totally a homemade kind of thing.

AVC: For the sequel, you’re like, “Why not? That was fun.”

AM: I mean… no one was really thinking there, were they? [Laughs.] We just did it again, you know?

Year Of The Gun (1991)—“Michael Dunn”

AM: If there was ever one movie that I did that I would love to have had another chance at doing, it would have been that one. I was wrong for the part. I was too young, and I was not right for it. But I love that kind of political intrigue kind of movie. But they’re hard to do, and it didn’t work.

AVC: John Frankenheimer directed. What was that like?

AM: John was a tough man. John was a tough man.

AVC: What’s the toughest thing he did?

AM: “Cut. That sucks.” [Laughs.] “Right, okay. Good, John. Any thoughts?” Anyway, John was tough. Wonderful filmmaker. But we had a tough time together.

Mannequin (1987)—“Jonathan Switcher”

AM: Mannequin somehow survives it all. It’s like a cockroach in a certain way. But Mannequin is lovely. It has a very innocent, sweet heart, and there’s not a cynical bone in its body. I think it was the first movie I was ever offered.

AVC: That you didn’t have to audition for?

AM: Yeah. And so I read it, and was like, “Yeah, we can do this.” And then right before we started shooting, I read it again, and I was like, “What? What am I doing? This is a movie about a guy who falls in love with a mannequin.” I told [my agent], “I’ve got to get out of this movie.” They’re like, “You read it. It starts on Monday. You’re not getting out of it.” Anyway, it actually works out fine, because it’s a very sweet movie in many ways. It’s so uncynical, and so unhip and savvy. There’s something about it that’s very pure. It’s lovely.

AVC: Are you also pro the Starship song?

AM: I like the Airplane, not so much the Starship, but people love that song. People love it. But all those songs that come to represent—people say, “How about this song?” I’m like, “I don’t really know that that was the song.” “That was the song from Less Than Zero!” “Oh, oh great. Yeah, no. Great.” I didn’t take them to heart, all those songs, so much. But I do cringe a bit on the St. Elmo’s Fire song. I think that one’s not so great.

AVC: It was written for a guy in the wheelchair. It was written for the songwriter’s friend. That’s why it’s called “Man In Motion.”

AM: Oh, now I feel really bad. Really? It was written for… I didn’t know that. No, I love that song. I’ve always loved that song. Wow, yeah. I feel terrible now.

AVC: I’m sorry.

AM: That has nothing to do with the movie, though. Anyway, that, okay… next!

AVC: Mannequin also reunites you with James Spader, who is like your nemesis in both Less Than Zero and in Pretty In Pink.

AM: Oh, I love James. I mean, James is so ridiculous in that movie.

AVC: Did he sign up because you did?

AM: Yeah, it was kind of “James, come do this movie! It’s going to be great! Don’t worry, it’s going to be great!” And like, “You can do anything you want because it’s so silly.” But no, I love James. And now we work together a lot on The Blacklist. So that’s fun.

Less Than Zero (1987)—“Clay”

AVC: That must have been a tough shoot, because it seemed like Robert Downey Jr. must have been going through a lot at the time.

AM: Well, and the story is no fun, and it was not really a great barrel of monkeys, that show. No. And we reshot a lot of that movie to water it down a bit and make it more of a “just say no” movie, which is a Nancy Reagan-era of that kind of thing. It just didn’t work. It was a classic example of studio executives buying a hot book and never having read it. And so when we saw the movie, we were like, “What? We can’t… this is horrific. We can’t fix this.” So they fixed it into making a mess of it.

AVC: Had you read the book?

AM: Yeah. I don’t think there’s a line of the book in the movie.

AVC: It’s very bleak.

AM: Yeah, I think Robbie was at the beginning of having a hard time there, yeah. He’s landed on his feet. He’s all right.

The Longest Way Home (2012)—author

AVC: You’ve had this large volume of work as an actor, and then you decide to become a travel writer. Can you talk about that transition?

AM: That was all an accident. I traveled a lot. I found travel changed my life. I love what it did for me. And I read a lot of travel [writing], and none of it seemed to capture what was happening to me when I was on the road, so I was just writing about it. And I met an editor then. And he eventually let me write for his magazine, and I just started writing. And then I won an award at it, and like anything, you win an award, and suddenly you’re a genius. And so then people who wouldn’t return my emails, they’re suddenly asking for me to write for them. And I’m writing back, “If I have time…”

But it’s wonderful. I love travel. I love travel writing. I think travel is a really important thing. I think it changes people. It’s not entirely a joke when I say I think travel is the last best hope for the world, in many ways. I think if people leave their comfort zone and get out of their routine and go see the world, the world would be a very different place, particularly Americans. Mark Twain has that famous [quote] like, “Travel is fatal to prejudice, bigotry, and narrow-mindedness.” Anyway, that’s my soap box. But I think that’s very true. And Americans would benefit hugely from traveling. So I started writing about travel, and it became suddenly this thing that I was doing as well. And then I wrote a travel memoir, and there it goes.

AVC: The way that you look at travel, it reminds me a lot of Rick Steves. His friends would shame him, like, “You’re traveling all the time.” And he’s like, “You’re sitting on a $2,000 couch. I’m on a $20 couch and I’m traveling the world.”

AM: Yeah, well done, Rick. You’re going to be stoned a lot though, Rick. He smokes a lot of pot, which he’s very vocal about.

But I agree, and I also do think that people don’t travel because they’re afraid. I don’t care what you say. It’s not that I don’t have time and that I don’t have money. Nonsense. You can travel incredibly cheap, and I prefer to travel incredibly cheap, because the closer to the ground you travel, the more you encounter real life out there. You don’t want to go stay in a beautiful hotel and all you get to know is the concierge. I just don’t buy it. I’ve done the math, and I’ve convinced friends: “Save your money. You know where you’re going. You need an incredibly cheap plane ticket, and you go places and stay for dollars a day.”

So I think people don’t travel because of fear. I think people don’t do most things they want to do because they’re afraid. And then they justify it with all sorts of other reasons, but I think fear dominates us in a huge way. For me, that’s the thing that travel did. It helped me recognize fear in my life and then walk through it. It changed my life in the sense that it helped me recognize how fearful I was in the world and walked through it. When I walked across the Camino De Santiago in Spain, I had an experience there of recognizing that power of fear in my life, which seems odd, because I had done all these public things like we’ve been talking about. And yet somewhere I knew that fear was lurking, and it was so ever-present in my life that I was not even aware of its existence.

AVC: Do you also travel with your family?

AM: I have a 15-year-old boy, a 10-year-old daughter, and a 3-year-old boy. We travel a lot. My wife is Irish, so we go back to Ireland a lot. I think you should just take kids where you want to go. Disney World is great—my son loved Disney World—but he much preferred the Sahara desert.

I think we should just take kids where we want to go and not go, “Oh, let’s take the kids to here!” I think traveling with kids is great and exhausting, and you swear you’ll never do it again every time and all that kind of stuff, of course. But it’s great, because I go through security, and it’s like, “Dad! You beeped!” And everything is an adventure. And I think making little citizens of the world is one of the best things we can do for our kids.

AVC: What did he love in the Sahara desert?

AM: Oh, dude. Have you been?

AVC: Sadly, no.

AM: The sheer vastness of it, and the nothingness there. It’s really overpowering. And my son buried himself in sand, and he’d just lay in the hot, warm sand, and it soothed him.

Lipstick Jungle (2008-2009)—“Joe Bennett,” director

Orange Is The New Black (2013-2017)—Director

The Family (2016)—“Hank Asher,” director

AVC: So, you’re doing all that, you’re writing, and you also started directing for TV.

AM: Yeah, I’ve been directing for about 10 years now. I started directing a show I was on, for Lipstick Jungle, and then I did different shows. And I do a lot of that show Orange Is The New Black and Blacklist and various shows. I like it a lot. It’s an interesting job, because I have every actor neurosis that there is, right? So I understand what the actor is dealing with. I’ve been on a set my whole life. I just know how sets run. I know what is wasting time on a set. It’s just a job that I found when I started doing it: “Oh, I have an aptitude for this, and I can do this. And I really enjoy it.” Not being the center of attention—I’ve found it to be really satisfying.

AVC: You did one of my favorite Orange Is The New Black episodes, “The Chickening.”

AM: Oh, yeah. Well, what’s interesting about that episode is it’s pretty self-contained, where a lot of that show isn’t self-contained. That was the fifth episode of the show as a whole, and shows tend to find themselves at about five. They go whoomp, and they land. I have a friend who says, “Don’t do early episodes. Come in at five, and you’ll look like a hero.” And in a certain way, it’s true, because the show just becomes itself by the fifth episode. The writing is figuring itself out, the actors have gotten bonded. The crew just settles by then. And water seeks its level, and that’s where it’s going to be. And that was episode five of that first season, and it really worked. Suddenly, it worked. That show worked from the get-go and still works. It’s a lot of fun. It’s like herding cats, that show, though. It’s bedlam, and it’s great. It’s not something you can control in any way. You just pen it in a little bit and let them go crazy.

AVC: It ended on such an intense note this season.

AM: Yeah, I directed the first one for the next season. It’s coming out, I think, in June. And it starts on an intense note.

AVC: Can you tell us anything about that?

AM: That’s it, that’s it. We’d have to kill you, of course.

AVC: I was very impressed with your appearance on The Family, and that you directed some episodes of that as well.

AM: I hadn’t acted in a number of years. So, it was really fun, if you can call that character fun, to go back and act again. I was reminded how much I really enjoyed it, and how it’s like breathing to me. I really enjoyed that again, and I was surprised. I was like, “Wow, this is really fun.” And I was playing a pedophile, so how fun a role is it? But I really enjoyed it. I don’t know what that says. And he was really a complicated guy, sort of isolated. I like people that are isolated. I find them interesting to inhabit.

AVC: You actually made that character sympathetic somehow.

AM: Well, that’s one of the things is somehow you have sympathy for this person. You go, “No, wait a minute. I can’t have sympathy for him. He’s horrible.”

AVC: But he doesn’t want to be like that.

AM: Right, well that’s the thing. He’s so full of self-loathing, and I think a lot of people can identify with loathing aspects of themselves and just their nature, trying to run from their nature and/or an aspect of themselves. People are complicated, you know? He was a guy who felt a certain way, and he wrestled mightily against acting on it. So that was interesting to explore him. I thought it was a really interesting show, but it probably never should have been on a network to begin with.

AVC: That’s true. It might have done better elsewhere.

AM: It probably would have, and it could have taken its time a little bit more if it were not on network TV, which it probably would have benefited from.

AVC: It’s interesting how much TV is changing, like how Orange Is The New Black’s seasons can be contained to 13 episodes. You don’t need to go to 22. You don’t need to stretch it out.

AM: I think those days are largely behind us. When we were doing the first year of Orange Is The New Black, remember, everyone was just thinking, “Netflix… they mail DVDs. What’s this going to be on?” “Netflix.” “But what’s it going to be on?”

And then when they said, “Okay, it’s a streaming thing. Okay. And we’re going to do all the episodes in one day.” And we all thought, “Well, that’s the stupidest idea I have ever heard.” Everyone, without question, goes, “That’s just really stupid. Why would they do that? It doesn’t make any sense.” And so, clearly, we were right again on that front. But it’s changed the whole world in the way people—obviously the way people view, but also the way stories are now written. People are writing now a 10-part movie that they know they’re going to watch in two days as opposed to having to leave it at a certain point for next Tuesday at 8. It’s changed the way stories are being told, which I think is fantastic.

AVC: Are you thinking about writing for film or screen or directing?

AM: I’ve always kept them very separate because I’ve had so much baggage with my film and television career that I’ve had so many mixed feelings about it. I loved that the writing was so separate and a creative rebirth to me. No matter what—and there were no votes. My vote was the only vote there was, which there’s something satisfying about that. I love collaborating with people, but it’s also nice to be like, “This is what I’m doing. You don’t like it? It doesn’t matter. It’s mine.” So I’ve just started to go, “Well, maybe they could come together and be useful to each other.” We’ll see.

Just Fly Away (2017)—Author

AVC: To that end, your new novel, Just Fly Away, is a YA novel told from the perspective of a 15-year-old girl who finds out a devastating secret about her family. Again, it’s such an interesting turn for you. What inspired you to write it from that perspective?

AM: That was a complete mistake, all of it. I was writing a book about a guy who had a one-night affair and a child came out of it. Because I was interested in the notion of secrecy and he kept this secret from his family—secrecy and marriage and how it corrodes, just holding a secret for a long time corrodes any intimacy like water torture, just knowing it makes it over years—it builds a wall. So I was writing this book for literally seven, eight years, and I couldn’t crack it. My favorite character was always the 15-year-old daughter, and one day, I just started writing from her point of view. “My dad has this kid across town. What’s that about?”

So suddenly things I had been struggling with for seven or eight years just pivoted, and there it went. And that big, wonderful Great American Novel that I had been writing fell like a tree in the woods and became a nurse tree to this novel that sucked all the nutrients out of it. Nothing about the two books are the same except the inciting incident, which is this girl finds out that she has a brother living across town, that her father had been lying to them, and everything she thought about her life is now turned on its ear, and she has to go find answers. And I knew right away that I was suddenly writing from a YA point of view. I could have written a book from an adult point of view about a 15-year-old, but there was something about the emotional immediacy and urgency that I really liked in YA. And I think more than 50 percent of YA readers are adults. So, there’s just something about the directness that I really liked, and I knew that I was writing to my 15-year-old self, and from my 15-year-old self. So, I just sort of jumped into the YA pool.

AVC: Was your son a teenager at this time, too? Could you use him as a test audience?

AM: He was 13, but my son has not read the book. I asked him if he wanted to, and he said, “I’ll wait for the audiobook, Dad.” And the funny thing about that is the publishers sent me some tapes of, or audio files, of readers for possibly reading the audiobook. And I was listening, sort of not paying attention, listening—next, next, next. Then I heard one that I was like, “Oh, I like that voice. Who is that?” It turns out when my son was 2, 3, 4, 5, we had this young, aspiring actress/babysitter. And she would come a couple of times a week and babysit for us. And it was her that was on the audiotape. So she’s going to read the audiobook. That was very cool for my son: “Oh, I’m definitely waiting for the audiobook now, Dad. I’m not reading it.” My kids have not read it. But I think it’s great. My kids have no interest in it—I’m just their dad, as it should be. They don’t care about that stuff.

AVC: But your son is becoming an actor, too, right? And your daughter was onstage as Matilda?

AM: Yeah, yeah. Against my better judgement, my children are curious about acting. My son just did his first movie, and of course the irony of it all is that Molly Ringwald played his mother. My world is just getting smaller and smaller. And my daughter was Matilda on Broadway in the musical Matilda.

AVC: That’s such a wonderful show.

MA: It’s great. We took her to go see Matilda, and she said, “I want to be Matilda.” I’m like, “Okay, sweetheart. Sure.” My daughter had been the frog in a second-grade school play. That was her theatrical experience. But they were looking online about all things Matilda. Buy a T-shirt, get the album, and saw that there was an open call—much like I once went to an open call—for Matilda. And she went, and suddenly she was Matilda on Broadway, which was wonderful and wondrous and horrifying all at the same time.

AVC: The McCarthy legacy continues.

AM: [Laughs]. Yes. We like to call ourselves the Von Trapp family.