Anna Karenina will receive a modern-day makeover in Netflix's first Russian original series

TV Features Anna Karenina

Netflix’s first Russian original drama series is in motion. A modern adaptation of Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina, with the working title Anna K, will bring a contemporary take to the socialite’s affairs.

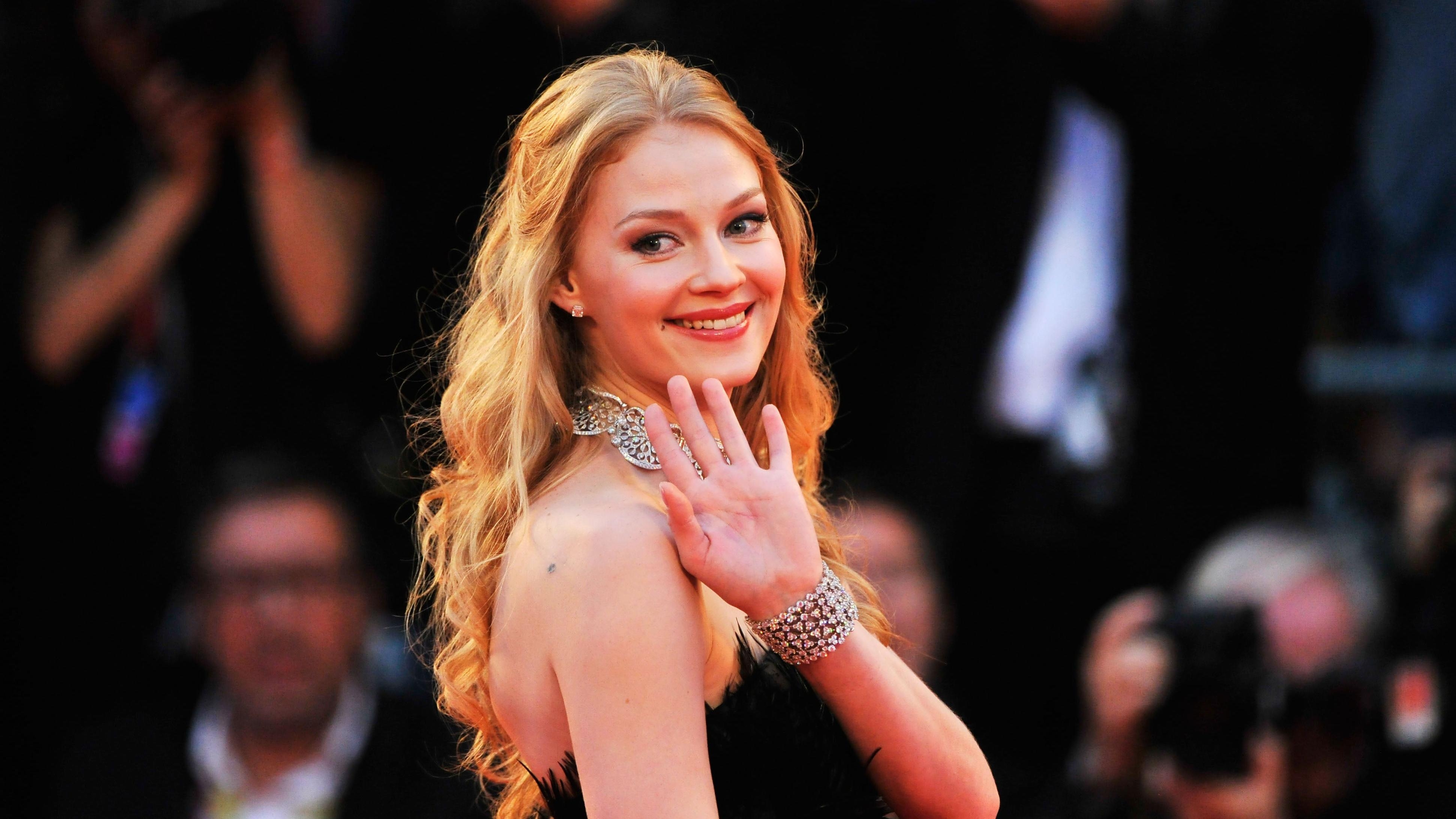

Svetlana Khodchenkova (Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy, Wolverine) stars as Anna, the wife of the soon-to-be governor of St. Petersburg, who falls in love with Vronsky, the affluent heir of an aluminum empire. Their affair soon begins to threaten their social and familial relationships, further unraveling as the two become more involved.

Considered one of the best novels ever written, plenty of Anna Karenina adaptations have been made across the world, the majority of the films set in the antiquated time period. However, Anna K plays out against the bustling city of Moscow, St. Petersberg, and the Russian countryside—all in a contemporary setting and in Tolstoy’s native language.

The series is written by Roman Kantor, known for Russian television series To The Lake. Director’s include Valeriy Fedorovich, Evgeniy Nikishov, Natasha Merkulova, Aleksey Chupov, and Kantor.

“To bring Anna Karenina into 21st-century Russia and to simultaneously introduce her to the whole world in her own language (and many others) through the miracle of Netflix is a dream come true for me,” Kantor says. “Quite literally so, as the idea for this TV series came to me in a dream and I have been chasing it ever since.”

No premiere date for the series has been set yet.

12 Comments

I loved the Keira Knightley film, it was fucking sexy. Captured the steam in that affair so well.

Spoiler: The first season ends with Anna singlehandedly stopping the train about to run her over using only the the power of her mind to crush the locomotive. Having for the first time tapped into the power long dormant, she wonders what to do next, at which point Nikolai appears before her and says “Come. There is much to tell you.” Cut to black.

This is just the person Russia needs to succeed Putin.

“A war is to be coming, Carl.” ~ Magnetov, X-Mans

“Only the chosen one can wield Chekov’s gun.”

Query: would Anna Karenina and Ulysses be so highly thought of without their final chapters, each of which presents (in a man’s imagining) a stream of consciousness representation of a female character? Giving a shit what women think: modernism?

Isn’t the final chapter of AK an interminable account of Levin undergoing a crisis of faith?

I’ll just point out that there’s actually a book in the vein of Pride and Prejudice and Zombies titled Android Karenina, where the love story happens among the backdrop of both a robot rebellion and alien invasion. It’s as awesome as it sounds.

that bad, huh

The miracle of Netflix.

How entirely pointless!The whole point of stories like Anna Karenina, which directly observe and criticise the moral codes and behaviours of their specific era, is lost when they’re transplanted into a completely different era, with different moral codes and behaviours. Modern attitudes toward marriage, adultery, duty, and female sexuality are not those of Anna Karenina’s era. To tell that story in the modern era would either be baffling, or would require changing so much of it that nothing but the names remained.There are some period stories that can be ‘modernised’ in this way meaningfully, because they’re sufficiently distinctive. “The Count of Monte Cristo”, for instance, can be recognisable – wronged man happens to become rich, reintroduces himself into the lives of those who wronged him many decades later pretending to be their friend (they don’t recognise him) but secretly working to destroy them all – even though a lot of social details (king vs napoleon, moral authority of ship captains, suicide of debtors, abortion, greek independence, etc) have to be lost or radically transformed. It’s a sufficiently unusual story to be a genre all by itself. But Anna Karenina? Not so much.