Clint Eastwood’s Sully is not a perfect film, but it comes close to being a great one as it turns the real-life emergency landing of a passenger plane in the Hudson River into a meditation on duty and crisis that’s more Bertolt Brecht than “based on a true story.” Showing its own integrity and persistence, the movie doesn’t offer a moment of triumph, but instead opts to repeat and re-stage the emergency and its worst-case scenarios in post-traumatic nightmares, lengthy flashbacks, and a hearing in which the pilots watch the incident recreated over and over in simulators, critiquing each. In all of this, Sully finds notes of absurd and macabre humor and poignant humanity—and a portrait of doubt that’s all the more memorable because it comes by way of the soft-spoken, mustachioed airline captain Chesley Sullenberger, one of the least compromised heroes in Eastwood’s latter-day oeuvre.

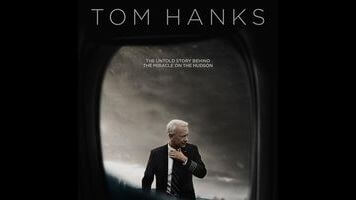

Sullenberger (nicknamed “Sully”) is played by Tom Hanks with the kind of from-the-gut effortlessness that has distinguished the great male performances in Eastwood’s films. One of the many gambits of Todd Komarnicki’s script is where it opens: Days after the incident, with Sully already a reluctant national hero. Living out of a Manhattan hotel suite down the hall from the flight’s other pilot, Jeff Skiles (Aaron Eckhart, sporting even more impressive facial hair in the form of a big ol’ Tom Selleck), he spends his days going from press interviews to meetings with aviation safety officials, haunted by the off chance that his improbable feat—which saved the lives of his crew and 150 passengers—might have been unnecessary.

This two-man unit of Sully and Skiles, the captain and the first officer, is the basis for the movie’s ideal of individuals working in concert. Eckhart is as lived-in and unshowy in his role as Hanks is in his, and in the final iteration of the icy water landing (this time seen only from the cockpit’s point of view), he concludes by throwing a look that doesn’t even register as acting until seconds later. Like the classic American studio films it sometimes hearkens back to, Sully is both up-front and subtle, lingering on the nuances of men and women who only ever speak their minds. The comparison that comes to mind is Howard Hawks, an individualist conservative (like Eastwood) who made movies about ragtag groups working together and enjoying the heck out of it.

Sully hums with an understated warmth, which extends to the broadly drawn passengers of US Airways Flight 1549, who are arguably the movie’s second biggest weak spot, after the substandard special effects. The exterior shots of the plane don’t work (they’re too plasticky and weightless), but also kind of do, considering that one of the movie’s rhetorical ideas is that nothing can perfectly recreate what goes into a real-life crisis. It develops its subtle themes through repetitions, whether it’s the near-real-time replays of the landing from different points of view or the way the film tracks Sully’s one-word under-reaction to the flock of Canadian geese that struck the plane’s engines (“Birds”). Over iterations, the latter becoming darkly funny (as repeated by the simulator pilots, reading blankly from a script) and then vulnerable and very human.

The French jazz pianist Christian Jacob provides one of the better scores in Eastwood’s later work, applied like a bittersweet afterglow to the post-landing scenes in Manhattan. But the emergency landing scenes are mostly music-free. Crisply, they cut around as cabin crew, air traffic controllers, Hudson ferry operators, and rescue personnel all make decisions based entirely on what they see on screens or hear over radios. Sully isn’t exactly a character study. It’s too generous with the other characters to be called that, and treats its protagonist as modestly as he treats himself; a couple of flashbacks to his early days as a young pilot and a few phone calls to his wife (Laura Linney) are just about all it provides in terms of biography.

But Sully is the central (and most compelling) figure in this plainspoken and disarmingly delicate conception of heroics, which might be Eastwood’s best work since Million Dollar Baby. Framing Sully and Skiles’ back-and-forths with stuffed-shirt officials and gawking strangers in his classically dramatic style, Eastwood is always on the verge of making a blunt point, but never does. From the variations, the forced smiles to TV hosts, and the discussions of whether or not the plane’s second engine (initially thought lost) was still working at the time of the landing emerges the impression that doing the right thing is not a one-time call, but just the most visible part of a continuing process.