Adaptations are tricky endeavors, pulling stories out of their original media and forcing them into new confines that can often jeopardize their integrity. The challenge is heightened when that source material is a game. Video game adaptations are common and rarely pan out well, with filmmakers simplifying long, interactive stories to create bland, passive viewing experiences. The board game adaptation is far rarer, and while these properties are regularly optioned by Hollywood studios, few make it to production. 2012’s Battleship and 2014’s Ouija have quickly been forgotten, but one board game adaptation has stood the test of time and become a beloved cult classic: 1985’s Clue. That film revealed the creative potential of the murder mystery board game, and Dash Shaw further explores that potential in the pages of IDW’s new Clue: Candlestick miniseries.

In the past year, IDW has released some exceptional licensed comics by cartoonists who write, draw, color, and letter the books on their own. After blowing readers away with his wild Transformers Vs. G.I. Joe miniseries, Tom Scioli returned to transforming vehicles for Go-Bots, crafting a sci-fi horror story that expands the Transformers rip-off in fascinating ways. Copra’s Michel Fiffe recently wrapped up his tribute to Larry Hama’s G.I. Joe stories in the G.I. Joe: Sierra Muerte miniseries, an exhilarating action extravaganza served with a dash of political commentary. Shaw has never worked on a licensed comic before, and his alt-comics background makes him a surprising choice for IDW’s Clue: Candlestick miniseries. His unconventional plotting and expressionistic visuals bring new psychological dimensions to the Clue narrative, inviting reader interpretation to make up for the loss of the interactive game element.

2017’s Clue by writer Paul Allor and artist Nelson Daniel was IDW’s first shot at adapting the board game for comics, and while it was a fun book, it primarily used the source material for narrative elements—characters, weapons, locations—rather than translating the game’s mechanics and the experience of playing it. Shaw makes a comic about the board game, incorporating the map, the game pieces, and a set of rules. He quickly puts readers in an investigative mindset by showing them the world through the eyes of Professor Plum, who scans objects, people, and spaces to gather minute details. Paranoia takes over when the point of view switches over to Colonel Mustard, a former special forces member living under a new name and in constant fear of discovery. Mustard follows every eyeline in a room, much like how Clue players are keeping watch of the people around them to determine who has which cards.

From the very start, Shaw establishes that this is a psychological drama by elegantly visualizing Professor Plum’s thoughts. A pair of lips appear outside of his window as he hears the whistle of the wind, and in a particularly striking panel, Shaw shows the wind traveling through a dense maze to Plum’s ears. Shaw takes a simple action and turns it into a complex image that puts the reader inside the character’s head.

Beginning on such a surreal note indicates that this isn’t going to be a straightforward murder mystery, and much of Clue: Candlestick’s allure comes from how Shaw ties imagery to his characters’ psyches. The maze motif resurfaces later when Mrs. White recalls a somber moment with Mr. Boddy in his hedge maze, with Shaw zooming out to show the pair’s placement within. Shaw uses the maze to show Boddy’s growing detachment from the rest of the world, isolating him in a mess of tangled paths with only his maid for companionship.

Shaw looks to the board game to define the aesthetic of this comic, using the square grid of the playing map as the dominant graphic design element. Checkerboards abound in this book, flying toward the reader on the cover and appearing all over the first page as the pattern for Plum’s curtains, eye mask, pillowcase, and blanket. The pattern returns as the backdrop for two panels detailing Mr. Boddy’s prized weapons and how they came into his possession, with Shaw changing the color arrangement of the squares for different effects: A lone white square sits in the middle of the rope’s loop to give the impression of the rope wrapping around a single point, and two white squares are connected to the end of the revolver so it looks like it is shooting a bullet. These are small visual touches that many people might skip past, but they reveal the specificity in Shaw’s work.

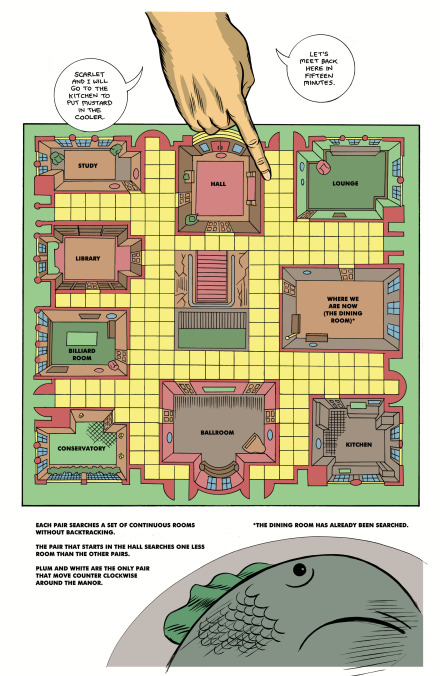

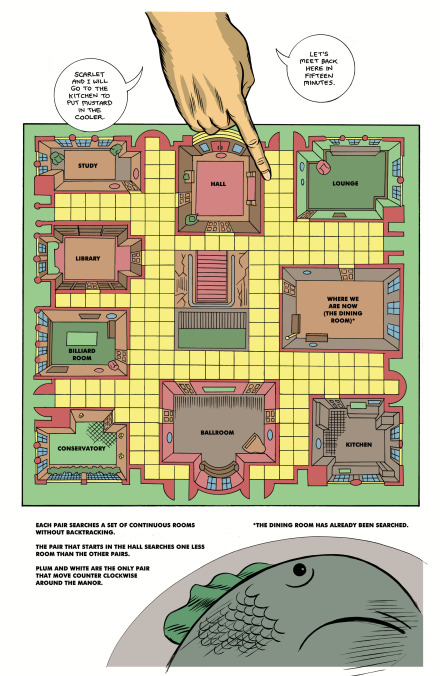

Other visual elements are less subtle. The colored stone pieces that cover each dinner guest’s house key are the same shape as the Clue game pieces. When the group decides to search the estate after the murder, Mrs. White pulls out the familiar map and lays it out on the table. Underneath the map are three sentences describing how pairs move through the house, written like game rules that will likely come back into play as the mystery grows. These are all ways that Shaw connects the characters’ experience to that of the players, but the comic goes an extra step to influence gameplay: The back cover is composed of seven Clue playing cards to be cut out, giving readers the core six characters and the titular weapon as drawn by Shaw.

In his back matter essay, “On Murder Considered As Recreational Activity,” Tim Hodler explores the origins of Clue, its psychological effect on the player, and its unique narrative qualities. The essay doesn’t specifically address Shaw’s work but it does illuminate it, breaking down the darker emotional elements of the game that Shaw expertly brings to the page. Hodler highlights why Clue welcomes adaptation thanks to its emphasis on plot and character, making the gameplay more stimulating.

It certainly stimulates Shaw, who rises to the adaptation challenge by cleverly contrasting the psychological heft of the murder plot with the absurdity of the game’s flippant approach to homicide. The game doesn’t ask you to sympathize with these characters when the cards are dealt, and after their murders in the comic, the victims appear before St. Peter and heaven’s pearly gates in small panels modeled after New Yorker cartoons. As in the film version of Clue, Shaw recognizes the humor baked into the Clue concept, ensuring that there’s always a sense of play as he pulls readers into this deadly game.

7 Comments

There was a Clue game for Super Nintendo, and it was kind of awkward in multiplayer mode, because if you wanted to look at your cards, you had to trust that the other players would look away from the screen. But the cut scenes were kind of amusing. Especially the end when the winner announces the murderer. If the winning character turned out to be the killer, they said something like “Oh yeah, I forgot I did it. I guess I’m going to jail then.”

Communism was a red herring!

The answer to every Clue mystery ever: it was that focking Colonel Mustard in the study with the candlestick.Nobody who has a mustache can be an innocent man!

LET US IN! LET US IN!LET US OUT! LET US OUT!

I’m going to go home and sleep with my wife!

Daniel Clowes should be getting a cut of the royalties.

Something I never thought of before occurred to me while I was reading this comic. If Clue were a real murder mystery, wouldn’t it be obvious whether or not the rope was the murder weapon? Yeah, it’d be weird for the murderer to use a gun or knife as a blunt force object, but possible. But there’s really only one way to kill someone with a rope.