Colson Whitehead thrives in the moral grays of Harlem Shuffle

With Harlem Shuffle, the two-time Pulitzer Prize winner makes a captivating foray into crime fiction

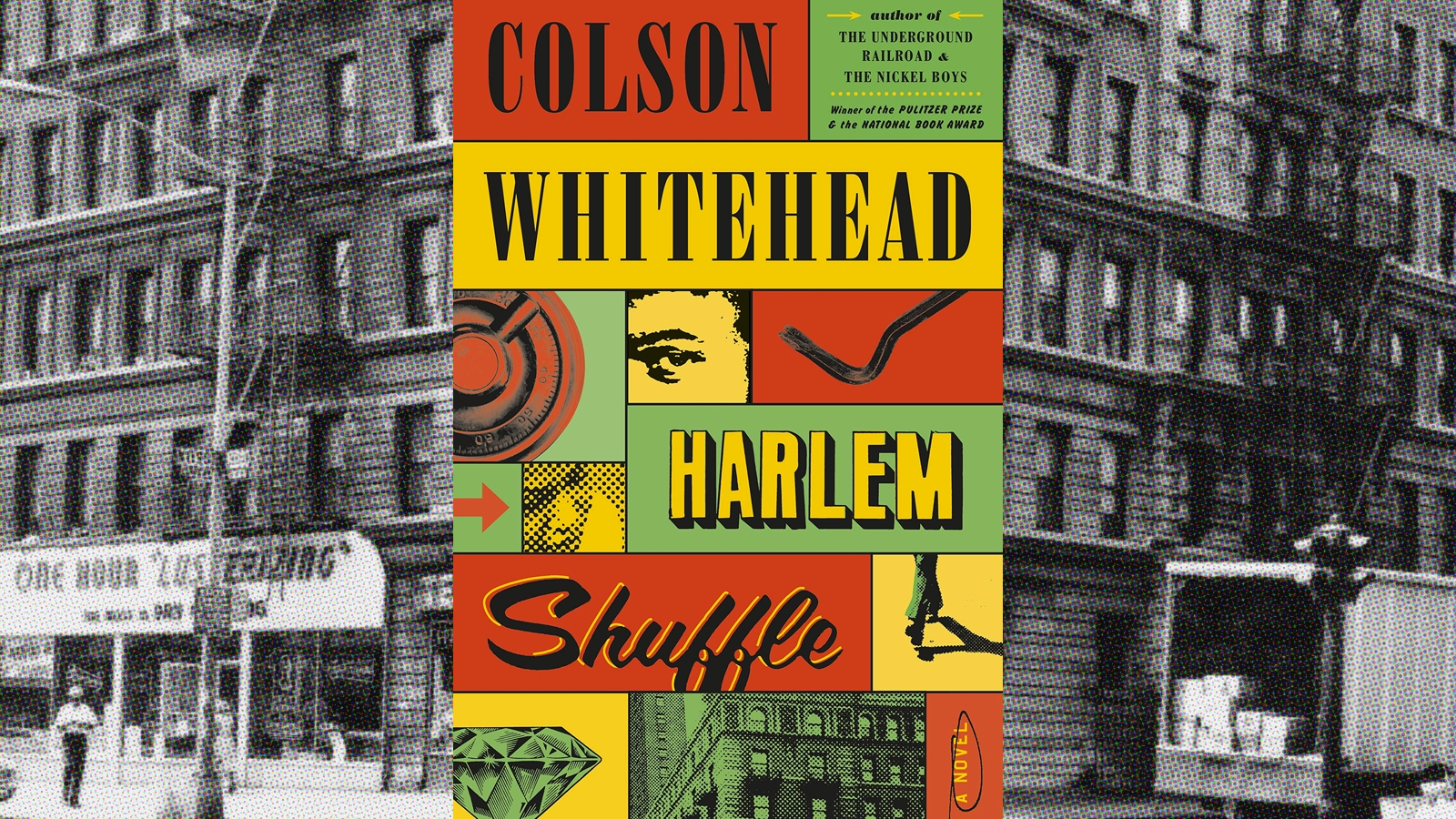

Image: Graphic: Natalie Peeples Books Reviews Colson Whitehead

Throughout his career, Colson Whitehead has moved between literary genres with brio, penning the gritty speculative fiction of The Intuitionist, the uproarious bildungsroman of Sag Harbor, and the engaging satire of Apex Hides The Hurt. When the New York native won back-to-back Pulitzer Prizes for fiction for The Underground Railroad and The Nickel Boys, two novels rooted in the racist history of this country and the resilience of Black Americans, fans might have guessed that Whitehead would go for the hat trick with another work of historical drama. But Whitehead has always been inclined to follow his muse; his varied bibliography is not just a sign of his protean ability to write within different genres but also a reflection of his wide-ranging tastes.

With Harlem Shuffle, Whitehead makes his foray into crime fiction, to transportive effect. There are capers, shady dames, hapless crooks, and cops for sale. The author’s crisp prose rounds the many narrative curves, racing from small businesses in Harlem to skyscrapers in Midtown. But this is no detective novel, where, despite the double crosses, an investigation ends in some kind of resolution. Rather, Whitehead establishes an ecosystem of crime, complete with low-level enforcers, their cutthroat capos, middlemen who bask in their plausible deniability, and the titans of industry for whom getting away with murder is only a tad more complicated than making a dinner reservation.

A meticulous researcher, Whitehead re-creates the Harlem of the late 1950s and early 1960s through sights—the Hotel Theresa, the Chock Full O’ Nuts diner—and sounds, including the music of the era and calls for justice during the 1964 riot. The Black glitterati are name-checked, along with crime bosses like Bumpy Johnson. What most grounds the novel in its setting, perhaps more than the rich historical details, are the characters: Harlem natives and transplants; strivers and schemers; the straight and the crooked. Some are the people that rose up in 1943, when a white cop shot a Black soldier who tried to intervene in the arrest of a Black woman, and again in 1964, when a white cop shot and killed 15-year-old James Powell. Others, like the fictional Big Mike Carney went “shopping” as their neighbors protested. Still others tried to effect lasting change in the wake of the uprisings.

One of Whitehead’s characters delineates these groups: “If they were good people, they marched and protested and tried to fix what they hated about the system. If they were bad people, they went to work for people like Dixon,” part of Harlem’s demimonde. But as the author and his protagonist, a furniture store owner and part-time fence named Ray Carney, understand, those lines are easily blurred, if not outright erased. A schemer by another name is a striver; today’s “rug peddler,” as Carney’s in-laws dismissively describe him, could be tomorrow’s ring-bearing member of the Dumas Club, a fictional association for Black entrepreneurs whose exclusivity is steeped in historical fact.

Like the city it’s nestled within, Harlem is marked by movement—some of it desired, much of it forced. As the author notes, many of its residents have crossed an ocean or are descended from those who did, often against their will. The face of the neighborhood, once predominantly white, changed after the Great Migration. Ray Carney finds himself at the center of these swirling currents as a man who’s become adept at facilitating the “churn of property” (ill-gotten and otherwise) of his customers and neighbors. Though he’s been in Harlem his whole life, he’s always been on the move, trying to outrun his father Big Mike’s legacy, hustling to ensure his children won’t have to do the same. But as Carney is referred to primarily by his last name, save for interactions with his wife and errant cousin, his efforts to distance himself would seem to be in vain.

The novel spans five years, one daring heist (which recalls the notorious Pierre Hotel robbery of 1972), a showroom expansion, multiple murders, the downfall of a prominent Black businessman or two, and innumerable slights to Carney. The store owner is as surprised by his ability to roll with the punches (and dole out a few vindictive blows of his own) as he is dismayed. But whether or not Carney has inherited his father’s proclivities along with his “worship of grudges,” early on, he realized that “living taught you that you didn’t have to live the way you’d been taught to live.” It doesn’t matter where you start, what matters is “where you decided to go.” For Carney, the destination is Riverside Drive, where he and his family can be on the periphery of the old neighborhood and the new.

Carney’s fate is the real mystery of Harlem Shuffle. The suspense comes as much from the family dinners—where the protagonist’s two sides, “the straight and crooked,” break bread—as the intricate capers, foot chases, and shootouts. It’s not just a question of whether Carney and his associates will make it out of this or that scrape, but if all of this will be enough to secure a spot on Strivers’ Row. Carney is easy to like: a family man who’s a bit of a square, who reckons with his flaws but refuses to be defined by them. The details of Carney’s struggle are all Whitehead’s creation, but the broader story is a classic one—trying to get ahead, by hook or by crook.

It is, in many ways, a very American story. Money can whitewash questionable beginnings, smooth over any rough patches. The most important thing is that you want to be something else; or, as Carney might put it, it’s okay to be “bent” if you plan to go straight eventually. With his latest successful genre exercise, Whitehead questions all manner of strivers, even the likable ones who seem to “deserve” more. In Harlem Shuffle, upward mobility is a means, not an end, and legitimacy a matter of perspective.