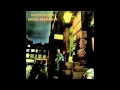

“Five years / That’s all we got.” So sings David Bowie with apocalyptic doom in his 1972 song “Five Years.” It’s the opening track of The Rise And Fall Of Ziggy Stardust And The Spiders From Mars, the critical and commercial apex of Bowie’s career as a glam-rock artist. Within a couple of years, glam would be on the decline, with Bowie moving on to more rarified, sophisticated pastures. Yet his ominous, five-year prophecy rang on.

As if embodying that prediction, punk rock exploded in 1977, a reaction against the decadent rock excesses of the ’70s, Bowie’s included. But Bowie couldn’t be easily lumped in with all the Led Zeppelins and Pink Floyds that the first wave of punks despised. Bowie, unlike most other major rock stars of the ’70s, did more than just give punks something to rebel against; he handed punk both fuel and fire.

“In the early ’70s David Bowie came out with Ziggy Stardust And The Spiders From Mars and they were like a proper band,” says Clash guitarist Mick Jones in John Robb’s Punk Rock: An Oral History. “It wasn’t like the David Bowie we all knew about, the ‘Space Oddity’ David Bowie. This was different. We took that seriously.” From that point on, Bowie’s gutsy, riff-slinging guitarist Mick Ronson became Jones’ guitar hero—thanks to songs like Ziggy Stardust’s “Hang On To Yourself,” whose buzzsaw snarl is just one step shy of what The Clash would wind up playing five years later—and Bowie became a glamorous guiding light.

Jones wasn’t alone. Bowie mania swept England in the early ’70s, liberating thousands of kids. While most glam was little more than dressed-up pop-rock, Bowie’s glam was hard-edged, challenging, and intellectual. Not to mention artistic. As Colin Newman of Wire, the most conceptual band of punk’s first wave, recalls in Punk Rock: An Oral History, “I was a big, big Bowie fan [prior to forming Wire]. There was a sense that Bowie was art […]. There was no other music about other than that. There was nothing else to talk about at the time. The fact that people were still talking about Bowie during punk just shows how important he was to that generation and not to be slagged in any way.”

Punk made a point of toppling heroes and holding nothing sacred, but Bowie was spared punk’s vitriol. Less present in England and the U.S. during punk’s 1977 explosion—during which time he had holed up in Germany to record his Berlin Trilogy—he became punk’s absentee father. Poly Styrene, singer of X-Ray Spex, would spin Bowie’s “Diamond Dogs” when DJing. The Sex Pistols’ Sid Vicious was, according to Marco Pirroni of Adam And The Ants (as well as Vicious’ bandmate in the first lineup of Siouxsie And The Banshees), “a tall, geeky kind of bloke into Roxy [Music] and Bowie. […] I think Sid would have wanted to be Bowie—but without the talent to pull it all off.” The influence was also visual. Brian Young of the Irish punk band Rudi “experimented spiking and dying bits of [his] hair, trying to copy Bowie’s spike top.” As did scores of others, resulting in the most common, recognizable punk style statement of the ’70s.

Few early punks dared to actually cover Bowie, but the London band Eater—all teenagers at the time, young enough for Bowie’s music to have imprinted them in childhood—released a cover of his 1971 song “Queen Bitch” in 1977. Punks love ironic cover songs, but there isn’t a trace of sarcasm to Eater’s “Queen Bitch,” just honest reverence to a raw, savage song that didn’t need much deconstruction to sound punk. “The artificial, trebly shriek of The Spiders From Mars deliberately alienated the older hippie audience,” observes Jon Savage in England’s Dreaming. The exact same thing could be said of punk.

Bowie’s friend and collaborator in the ’70s, Iggy Pop, is generally credited with being the true godfather of punk. Listening to Pop’s output with The Stooges, that title is hard to deny. But The Stooges weren’t a well-known band at the time—and many early punk musicians, including The Fall’s Marc Riley to The Prefects’ Robert Lloyd, have pointed out that Bowie was their gateway to Pop’s music, as well as to another of punk’s main inspirations, The Velvet Underground, whom Bowie covered, championed, and paid stylistic tribute to in songs like “Queen Bitch.” Bowie toured the U.S. and the U.K. as a keyboardist in Pop’s backing band in 1977, and Ian “Knox” Carnochan of the seminal punk band The Vibrators has attested to the eminence this granted Pop in the eyes of punks.

Some punks did more than simply acknowledge Bowie’s inspiration in hindsight—they played glam themselves before going punk. While still an awkward kid from Queens named Jeffrey Hyman, Joey Ramone was the singer of a glam band called Sniper. In Performing Glam Rock, the pre-leather-jacket-and-jeans Ramone remembers, “I used to wear this custom-made black jumpsuit, these like pink, knee-high platform boots—all kinds of rhinestones—lots of dangling belts and gloves.” (In 1980, Ramone wound up attending a Clash concert in New York with none other than Bowie, no stranger to knee-high platform boots himself.) Across the Atlantic, The Adverts’ T. V. Smith cut his teeth in a glam group called Sleaze, which played “self-written songs influenced by […] ‘Rebel Rebel’ Bowie.” As the demo recording of Sleaze’s “Listen Don’t Think”—which later became The Adverts song “Newboys”—shows, there was a very thin line between late-era glam and proto-punk in the mid ’70s.

Riffs and attitude weren’t the only things that linked glam and punk. Both movements embraced self-reinvention. Years before punk’s inaugural class took names like Joey Ramone, Poly Styrene, Sid Vicious, Johnny Rotten, and Joe Strummer, glam rockers—led by Bowie, born plain old David Jones—recast themselves in glittering new personas. For glam, it was a way to elevate and escape sometimes grim surroundings, like Bowie’s own working-class background. For punk, it was a way to amplify and own that grimness. “These [punk pseudonyms] clearly could not be easily domesticated,” writes Dave Laing in One Chord Wonders: Power And Meaning In Punk Rock. “They announced themselves as artifice. As chosen names these were clearly ranged on the side of explicitly artificial.”

Paradoxically, punk was seen as gritty and realistic compared to glam. Yet punk used some of the same creative tools that glam did, only to realize an opposite effect. In both cases, it was an attempt to make oneself larger than life, to sculpt an identity—or in the case of punk, to proudly scavenge one out the trash bin, reveling in the deprecatory irony of virtual street urchins with grand stage names. As Christopher Sandford notes in Bowie: Loving The Alien, “Glam innovated the idea of the rock performance persona as a self-declared construct that was also fundamental to punk.” Howard Devoto of Buzzcocks and Magazine agrees, saying in Punk Rock: An Oral History that “the artificiality of glam rubbed off on punk.” In this case, artificiality isn’t a bad thing, even considering punk’s ethos of authenticity. Self-reinvention was a way to turn Bowie’s confrontational methodology—that “artificial, trebly shriek”—into a double-edged scalpel.

Another apparent split between Bowie and punk is over a related issue: fantasy versus realism. Bowie’s lavish imagination and knack for science fiction appears at odds with punk’s snub-nosed, street-smart attack and love of social protest. Punk had little use for science fiction or fantasy, except as pop-culture junk to recycle—barring a couple of notable exceptions, such as X-Ray Spex’s unnerving speculation genetic engineering and technological dystopia. “I wanna be Instamatic / I wanna be a frozen pea / I wanna be dehydrated / In a consumer society,” screams Styrene in “Art-I-Ficial,” one of the most scathing tracks off the group’s 1978 album Germfree Adolescents. But Bowie’s work incorporated far more realism than its given credit for, even if his fears about the present were often couched in fantastical, paranoiac daydreams about the future. Diamond Dogs, his bleakest album, draws heavily from George Orwell’s sci-fi classic Nineteen Eighty-Four, even going so far as to have a song named after the book; at the same time, it was a reflection of the urban decay and oppressive economics the day, concerns that punks both opposed and perversely fetishized.

As it turns out, one of Bowie’s biggest acolytes in the punk scene, Mick Jones of The Clash, bridged Bowie’s dark fantasy and punk’s social realism. Marcus Gray’s Last Gang In Town: The Story And Myth Of The Clash points out how music journalist Pete Silverton “talked about the ‘SF/fantasy phraseology’ of [The Clash song] ‘Remote Control.’” Written by Jones and appearing on the band’s debut album, The Clash, “Remote Control” imagines a deliberately, dramatically exaggerated England circa 1977, one where urban claustrophobia, totalitarian authority, and a robotic kind of daily routine—“Push a button / Activate / You gotta work, and you’re late”—reigns.

Adds Gray, “The Clash might have more than a hint of dirty realism in its language and situations, but it is as much a work of the imagination as David Bowie’s The Rise and Fall Of Ziggy Stardust And The Spiders From Mars and Diamond Dogs. […] Like Bowie before them, The Clash were walking around already trodden by such literary luminaries as George Orwell, J. G. Ballard, and Anthony Burgess; The Clash is Nineteen Eighty-Four meets High-Rise meets A Clockwork Orange, with tunes.” One listen to another Clash classic, “London Calling,” only drives that point home. In it, a full-on apocalypse has come to London: “The sun’s zooming in,” and everything from ice ages to meltdowns to famines to floods to zombies are on the way. Bowie himself couldn’t have made a more chilling prediction.

Still it’s The Clash’s “1977” that neatly bookends Bowie’s “Five Years.” A checklist of economic ills, boredom, and wounded frustration, it couldn’t be further from the grandiloquent gestures David Bowie had made in 1972. “You better paint your face,” Joe Strummer sneers, a jab that very well could be aimed at the cosmetically colorful glam artists of Bowie’s generation—really only a half generation away from the punks. Then, at the end of the song, Strummer shouts out a countdown of societal malaise that ends with “Here come the police / In 1984!” It’s a clear reference to Orwell’s book, the one from which Bowie borrowed so much. And in that moment, it’s as though punk had picked up a torch that Bowie had left sputtering.

Not all punks worshipped Bowie, openly or otherwise. The Sex Pistols’ Johnny Rotten approached Bowie’s influence, and that of glam in general, in a more dismissive way, saying in Punk Rock: An Oral History that “The T. Rex/Bowie period was for very young kids. Pop with lipstick. They got bored when they grew up […] and were desperate to look into anything else.” If there seems to be a bit of projection on Rotten’s part, that doesn’t dull his point. Steve Jones of The Sex Pistols found a more direct way to channel his desperation during the glam era: He stole microphones and a PA system from the stage of a Bowie concert one night in 1973, which he used to start a new band—one that would eventually become The Sex Pistols.

In the same book, Buzzcocks’ Steve Diggle agrees with Rotten, stating that by the time punk came around, “Bowie […] had peaked and we needed something else.” Mark Stewart of the seminal post-punk band The Pop Group puts it even more simply, stripping away the myth and mystique: “Through Bowie, a lot of kids were into dressing up and having a laugh.”

The Pop Group, like most post-punk outfits that sprang from punk in the late ’70s, wasted no time in cutting any lingering ties to rock traditionalism—even if it was Bowie’s avant-garde mutation of rock. If anything, post-punk bypassed Bowie altogether, although they picked from many of the same inspirations he’d chosen in the ’70s after abandoning glam, including funk, Krautrock, and minimalism. A few bands of the post-punk crop, however, were lavish in their Bowie worship. Bauhaus covered “Ziggy Stardust” and named a song, “King Volcano,” after a phrase from Bowie’s “Velvet Goldmine.” (The genre that Bauhaus popularized, goth, feels as if it could have been distilled straight from Bowie’s 1974 song “We Are The Dead.”) Gary Numan took one sliver of Bowie’s image and sound, the synthesized android, and expanded it into an entire career. And one of Joy Division’s earlier names, Warsaw, is a reworking of the title of the 1977 Bowie song “Warszawa”—even as the band’s singer Ian Curtis swiped Bowie song titles like “Candidate” and flaunted his love of Bowie’s distinctive baritone in his own gloom-steeped croon.

Bowie’s massive influence on post-punk’s offshoot, new-wave pop, has been vastly catalogued, from the stylish, plastic soul of the New Romantic movement to Peter Schilling’s fanfic-in-song-form, “Major Tom,” to Jim Kerr’s undeniably Bowie-esque croon on Simple Minds’ “(Don’t You) Forget About Me,” one of the definitive anthems of the ’80s. (Simple Minds even named itself after a line from Bowie’s “Jean Genie.”) Bowie himself became the figurehead of the new-wave era, yet another reincarnation in a career famous for them. But as Bowie, for the first time, began to follow artists who had gotten their start by following him, he momentarily lost much of the singular luster that had sparked punk in the ’70s.

“The great joy of bands like […] Bowie,” says TV Smith, speaking about glam’s heyday in Punk Rock: An Oral History, “was that they always had their own individual thing, regardless of what was going on around them. And that’s what I felt about punk.” When Bowie himself was asked to describe punk in an interview in 1979, he summed it up, with typical dry wit and insight, in four words: “A very important enema.” No punk could have put it better.