There is no progress without hope. Belief in a better world drives social and political change; it’s the flame that creates an inferno when it spreads to enough people, motivating them to take action to achieve a shared goal. Hope alone won’t save the world, but we’re doomed without it. Eleanor Davis is a cartoonist preoccupied with hope and the role art plays in encouraging this feeling. In her exploration of this idea, she immerses herself in hope’s opposite, giving in to apocalyptic thinking in graphic novels like Why Art? and her new release from Drawn & Quarterly, The Hard Tomorrow.

While Why Art? offers a much more fanciful, metaphorical look at the potential end of the world, The Hard Tomorrow takes a grounded approach amplifying the current socio-political climate. In the year 2022, Mark Zuckerberg is president of the United States and anti-protest legislation now classifies megaphones as criminal instruments. There are still activist groups fighting the fascist state—the government’s use of chemical weapons is a key point of protest—but resources are dwindling and the government is becoming more aggressive toward anyone who voices opposition. Hannah and Johnny live off the grid in the woods, and they’re trying to get pregnant despite all the indicators that society and the environment are on the brink of total collapse.

The Hard Tomorrow drops an emotional bomb before the story even begins, with one of Davis’ dedications going to the child she expects to have in three months. This dedication is an apology, asking forgiveness for bringing their child into “this beautiful and terrible world.” It’s the starting point for one of the book’s major themes—the internal conflict of desperately wanting a child but dreading the thought of bringing new life into a crumbling environment—establishing an autobiographical connection between the author’s anxieties and those of her main character. Hannah’s experience is highly specific, and because Davis’ storytelling is so natural and lived in, Hannah’s feelings of uncertainty and fear become universal to anyone who feels a surge of panic when they hear about current events.

Davis’ art style is vital to this emotional rapport. When you simplify a character drawing, it becomes easier for the observer to project their own identity onto it—hence why basic smiley emojis have become a shared visual language we use to express our emotions. This simplification is an essential reason why cartooning is such an expressive art, and Davis is a master of creating distinct characters with minimalist linework that invites deeper personal connection from the reader. The acting is full of emotion, and Davis captures facial expressions, body language, and gestures with curving, wiry lines that imbue the artwork with both spontaneity and grace.

This overall simplification also adds emphasis to images that are drawn in a more detailed style. In a particularly ominous splash page, Davis switches to more realistic rendering to give physical weight to a handgun one of the characters receives. The intricate detail pulls the reader into a more naturalistic atmosphere as Davis zooms in on two hands holding the weapon, reminding us of the very real destructive power contained in this small but surprisingly heavy metal object.

There’s a lot of pointed commentary in The Hard Tomorrow, most of it directed at the rise of a fascist government and militarized police force. An interaction with a sympathetic traffic cop gives Hannah a modicum of faith in these agents of unjust laws, but she sees the limits of that sympathy when she encounters that same cop in the middle of a riot, beating up peaceful protestors and smashing smartphones recording the injustice. A person’s capacity for compassion disappears when they’re given orders to violently squash the spirits of people fighting for human rights, and in the chaos that comes after the tear gas, any consideration for the individual is replaced by the directive to dismantle the group.

Hannah’s friend and fellow activist, Gabby, gives her a hard time when she hears about the traffic cop, but Gabby’s viewpoint isn’t presented as infallible. In Gabby, Davis depicts an activist who is still dedicated to fighting a corrupt authority, but has lost hope that things will ever get better. She’s resigned herself to inevitable dystopia, putting herself at odds with Hannah’s hopeful viewpoint. When the two of them go foraging in the forest, Gabby’s primary focus is on the rot spreading across the plant life. All she sees is the decay, which is why she lashes out at Hannah after finding out she’s still trying to have a child. Hannah eventually can’t take it anymore, screaming at Gabby, “What do you think everybody’s been fighting so hard for? For a peaceful future, Gabby! For the future!” Davis frames Hannah in lush foliage here, using the natural imagery to accentuate her optimistic dream.

Davis does not create joyless art. No matter how intense the subject matter, she finds moments of humor that make the reader want to spend time with these characters and emotionally invest in their struggles. The first meeting of Humans Against All Violence (H.A.A.V.) establishes its members as compassionate and funny, and even though they are doing very serious work, they still find pleasure in each other’s company. Most of the humor comes from the elderly woman Hannah cares for, first in her horrified response to Hannah’s haircut and later when she offers some advice on getting pregnant. Sitting naked in a chair while Hannah washes her, the old woman grumbles something that makes Hannah get up close. Davis zooms in even closer to set up the hilarious punchline, with Hannah focusing her attention just to be told that her husband should stop wearing tight underpants.

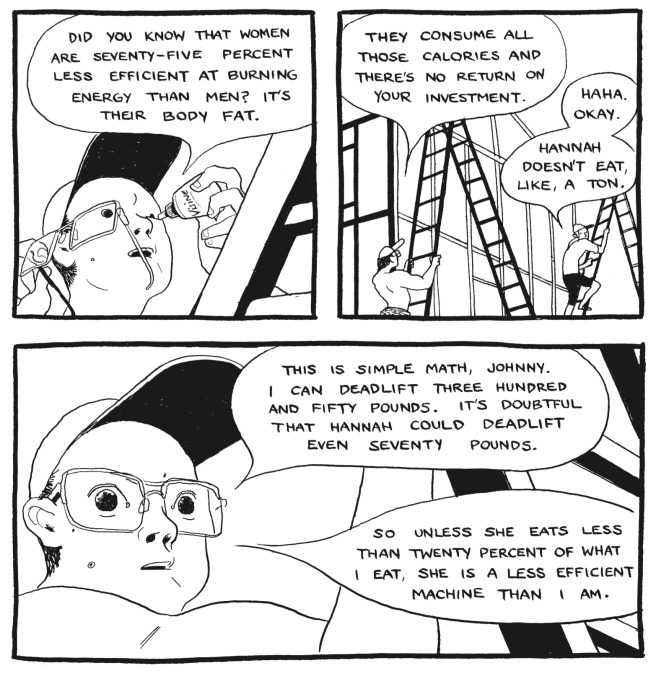

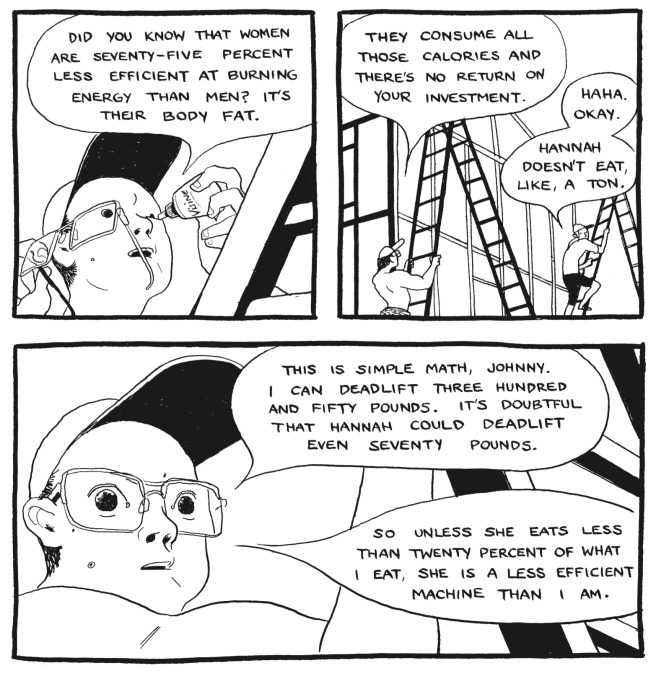

While Hannah devotes her attention to activism, Johnny chills at home smoking and selling weed, making no progress on the house Hannah hopes to have built by winter. When he does start building, he does so with the help of a paranoid survivalist, Tyler, who considers women to be dead weight and believes that the president has Facebook-powered drones in the air. Tyler provides a contrast to the efforts of the H.A.A.V., isolating himself so he can build up a stockpile of weapons on a fortified compound. This storyline builds to a shocking conclusion, taking a turn that addresses how political forces both compel the folly of man and become a scapegoat for it.

You can buy Davis’ comics digitally, but she puts so much thought into the physical object that I always recommend seeking out a printed copy. The Hard Tomorrow is a matte hardcover, soft to the touch but durable and portable. The bright blue background of the cover carries over the endpapers, wrapping the story inside the optimism of a clear blue sky. These design decisions all play a part in the book’s emotional tapestry, but the high point of this intersection between design and narrative comes during the book’s final pages. Like the gun moment, it’s a sequence where the act of holding is very important, presenting five two-page splashes all from the same point of view and drawn to scale. This puts the reader even deeper inside the holder’s perspective, and the book’s size is what sells the effect. Each small change from splash page to splash page increases the gravity of the life-affirming event, ending the story by presenting readers with a physical embodiment of hope in the palm of their hands.

7 Comments

I’m not a fan of Facebook (or social media in general), but all this Zuckerberg is a supervillain trope is getting a bit much. I remember the 1990s when Bill Gates was seen as Satan himself, and now he’s this guy that people look up to as he goes around the world trying to stamp out malaria. I wonder if Zuckerberg will end up experiencing a similar transformation.

That says more about the general cultural amnesia than it does about Gates.

I dont think it’s cultural amnesia. I hated Gates in the 90s because he made a shit product and used anticompetitice practices to create a monopoly and destroy small companies. I have decided that is outweighed by his incredible philanthropic work both in donating his personal wealth and lobbying other billionaires to donate theirs. He’s saving hundreds of thousands, possibly millions of lives. I’ll happily forgive a lot for that.

There’s been a real resurgence of Marxism and archaism in artistic motivations, and it’s important to remember that for these people mainstream political life is fascist, racist, and oppressive. It seems perfectly natural to this cartoonist that a billionaire entrepreneur would criminalize free speech and use chemical weapons on their own citizens, because their view of wealth and the people who have it is binary. Of course we usually don’t acknowledge the absurd political underpinnings of ‘important’ statements like the one this artist is making because that would expose the absurdity of the message.

Art is subjective. Illustration sucks. No thanks.

This doesn’t sound like the artist actually believes in hope. Like they’re working it out on the page, but even the hope that her characters cling to is out of reach in reality. I do like when artists vary their detail or realism level within the same work, reinforcing the importance or relevance of different moments in the story or even in day-to-day life.

The glimpse this gives of the cast of characters is enough to tempt me into volunteering for Zuckerberg’s campaign.