Graveneye’s stunning atmospheric horror offers a perfect close to spooky season

Sloane Leong, creator of A Map To The Sun, builds on a powerful legacy of queerness and women in horror

Aux Features Prism Stalker

As autumn draws to a close, a few more tales of terror are hitting shelves, though none of these fictional fears are quite as worrying as the frightening tangle of the global comics supply chain. Graveneye is a standout from the ever-growing list of excellent comics from TKO, and offers a perfect close to the season of scares.

Writer Sloane Leong is perhaps best known for A Map To The Sun, one of the best graphic novels of last year. Leong both wrote and drew that book, a queer coming-of-age story set against the backdrop of basketball and Los Angeles. On the surface Graveneye seems like a departure in both theme and tone, but there are similarities—not just with A Map To The Sun but also Leong’s earlier sci-fi comic Prism Stalker, as all three tackle themes of belonging and finding your sense of place, as well as starring queer women.

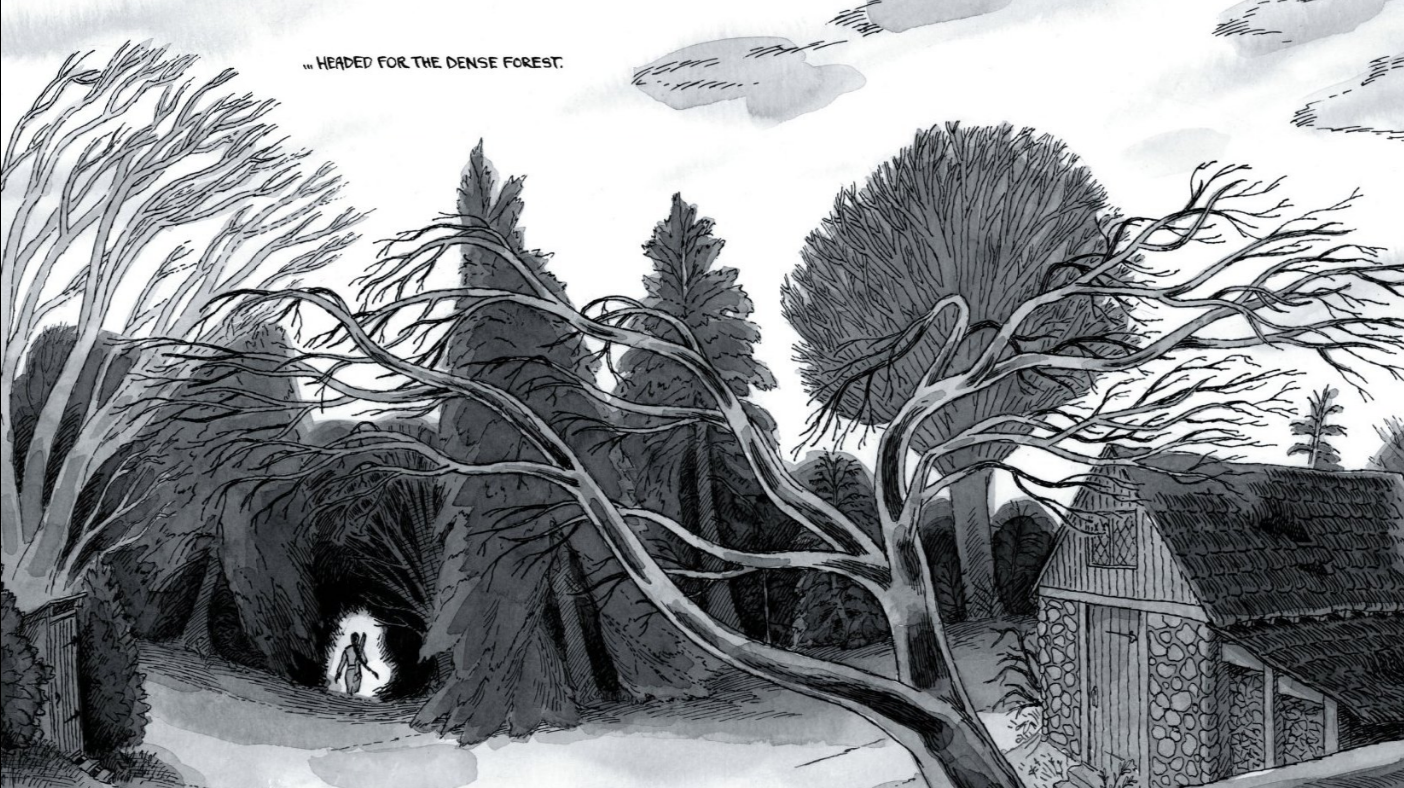

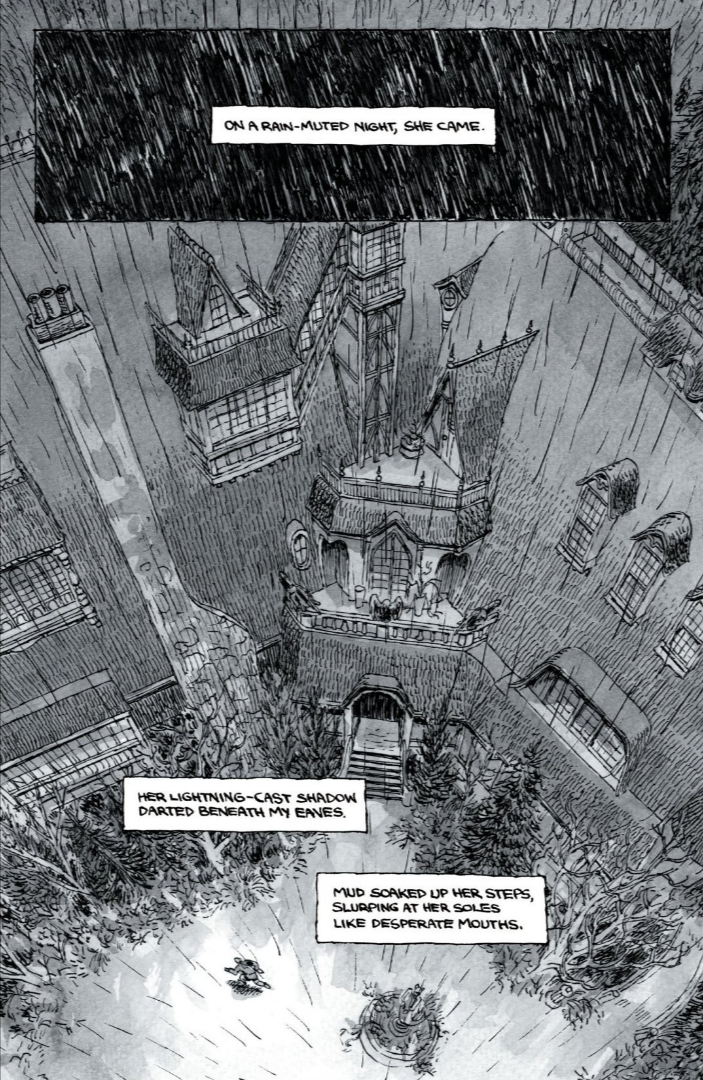

Instead of hot and sunny Los Angeles, the book is set in the sort of house that was made for haunting: remote and sprawling, resting on wealthy but slowly rotting foundations. The house’s owner, Isla, has a cellar full of secrets and a timid new maid named Marie. As the story progresses, Isla finds herself fighting the temptation to let Marie get close enough to see the the darkest parts of herself. Graveneye digs deep into the pain of its main characters, respecting it but refusing to shy away. It is both raw and calculating, thoughtful in how layers are peeled back to reveal the truth of each character and the world they occupy.

The book is undeniably queer, though in a different way than Leong’s previous work. Isla and Marie are pulled into a cycle of attraction that is shy at first, but quickly escalates. Affection, adoration, lust, obsession, and possession melt into a confusing tangle, without being solved or defined. It can be tempting to offer an easy resolution in such stories: to push the narrative and give characters and readers alike a clear feeling that one emotion will win out over the others. Queer characters are so frequently reduced to cannon fodder and violent endings that the pull toward happy conclusions can feel insurmountable, but Graveneye steadfastly maintains that none of the complicated loves which the main characters feel are more correct or desirable than the others. That ambiguity only adds to the pressure and terror Leong has crafted as Isla grapples with the violence at her core—and her desire to be closer to Marie.

Though the story would have been excellent no matter the visuals, artist Anna Bowles’ work commands attention and elevates the story to something more visceral and powerful. Given that this is her first major published work (while working with a writer who is also an accomplished artist in their own right), Bowles was likely contending with a lot of pressure.

She handles it with great skill: The limited palette of black, gray, white, and red keeps Graveneye atmospheric and unsettling, drawing the eye to the heat of anger or bright blood as violence steadily increases with every turned page. Without the benefit of a soundtrack, comics can sometimes struggle with building a sense of kinetic dread, but Bowles’ art pulls readers deeper into the story and ratchets the tension ever higher until it finally breaks.

The color palette and the growing sense of terror bring to mind a lot of acclaimed comic writer Emily Carroll’s work; Graveneye can absolutely take its place alongside her titles in the ever-growing list of excellent contemporary horror comics. With its unique narration perspective and focus on place, the book also brings to mind The Haunting Of Hill House—both the Shirley Jackson novel and Mike Flanagan’s Netflix miniseries. (There’s also a quiet hint of the much-maligned 1999 film adaptation, The Haunting, as it’s easy to picture Catherine Zeta Jones and Lili Taylor as Isla and Marie.)

There are even echoes of Wide Sargasso Sea, reminding readers of how family and wealth can contort women into monstrousness. Graveneye offers a must-read “Beauty And The Beast” story that adds something special to the deep history of women in horror, especially women who are deemed too queer or too far outside the realm of acceptable femininity.

2 Comments

I always played as Trevelyan. NO ONE could beat me in the Complex.

The writer of this piece is a talentless hack.