Ken Burns’ Muhammad Ali documentary is comprehensive, expertly crafted, and inessential

The four-part PBS series covers its subject well, but not as well as the many, many other films about Ali

TV Reviews Ali

Throughout Ken Burns’ long career as a documentarian and a PBS pledge-drive favorite, he and his team of collaborators have generally worked in two modes. Sometimes they go big, taking on huge topics like jazz, baseball, country music, national parks, and wars. And sometimes they go small, crafting detailed portraits of major cultural figures like Ernest Hemingway, Jackie Robinson, Frank Lloyd Wright, and the Roosevelts. In either case, Burns’ team uses their subjects as a way to explore the best and worst of American history: the larger-than-life celebrities, the racial and class strife, and the ways some brilliant men and women have used the ideals of liberty to inspire others.

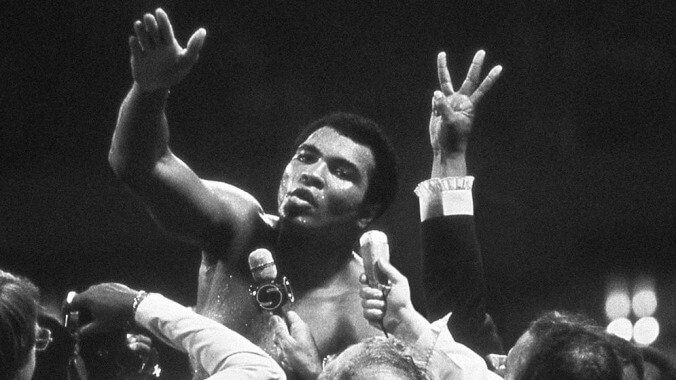

In Ken Burns’ four-part Muhammad Ali—co-directed with his daughter Sarah Burns and her husband David McMahon—the documentarian and his crew have a subject almost too perfect. Born in Louisville, the heavyweight boxing champion once known as Cassius Clay had a rich life: winning an Olympic gold medal, challenging a bigoted establishment, offering aid and support to the needy around the world, and entertaining millions with both his athleticism and his outsized, publicity-generating personality. It’s impossible to make a documentary about Ali without running smack into many of Burns’ recurring themes. But there’s the problem: Muhammad Ali’s story is so ripe for the telling that it’s actually already been told—over and over, in print and onscreen, for decades.

Want to know more about Ali’s conversion to Islam and his friendship with Malcolm X? Netflix’s Blood Brothers is a very good documentary about that very topic. Interested in Ali’s three-year exile from boxing, when he fought in court to prove he was a legitimate conscientious objector to the Vietnam War? That’s covered splendidly in the 2013 doc The Trials Of Muhammad Ali. Ali’s thrilling mid-’70s comeback, culminating in the defeat of George Foreman in the legendary “Rumble In The Jungle” match? Leon Gast won an Oscar for his brilliant 1996 film about it, When We Were Kings. An over-the-hill Ali using racially charged language to humiliate his former friend Larry Holmes before a title fight? Cinematic luminary Albert Maysles explored that in the great 2009 30 For 30 episode “Muhammad And Larry.” There are nonfiction films about his final Joe Frazier bout, and about how it felt to face Ali; just two years ago, director Antoine Fuqua and HBO produced a career-spanning doc.

The Burns/Burns/McMahon Muhammad Ali documentary runs for over seven hours, but it doesn’t tackle any one topic in as much depth as most of the aforementioned films. Yet each of those docs does in its own way cover the larger arc of Ali’s life, framed by the smaller fragments. The same can be said of director Michael Mann’s outstanding 2001 biopic Ali, with Will Smith playing the champ during the heady decade between 1964 and 1974; as well as Regina King’s 2020 adaptation of Kemp Powers’ play One Night In Miami, with Eli Goree giving a great performance as Ali, hanging out with Malcolm X, Jim Brown and Sam Cooke after winning his first heavyweight title.

So there’s the bad news: The Ken Burns collective has been scooped this time out. There just aren’t that many juicy Ali anecdotes that haven’t been told, and told a lot. As for the good news? Well, for anyone who doesn’t want to watch a half-dozen other movies to learn more about the life and times of Muhammad Ali, this new series will definitely suffice.

Burns and company don’t shake up their house style here. Muhammad Ali leans heavily on an authoritative-sounding narrator (Keith David, in this case), alongside thoughtful comments from excellent journalists and writers (including David Remnick, who wrote one of the best books about Ali, King Of The World), in between still photographs and vintage clips that in some cases haven’t been seen before by anyone other than archivists. Boxing fans in particular should love how much of these seven-plus hours are dedicated to extended footage of Ali’s fights, supported by keen analysis. (The doc’s creative team subtly enhances those old broadcasts, adding quietly atmospheric sound effects to help make them feel more visceral.)

This, again, is not that unusual for films about Ali. When We Were Kings, for one, is like a graduate-level seminar in fight technique. Still, one advantage that this series does have over the previous documentaries is that the experts are able to chart the changes in how Ali boxed across his 20 years as a pro: from the young man who danced around the ring and had a quick enough reaction-time to duck backward from punches, to the middle-aged monolith who stood his ground and took blow after blow, ultimately suffering permanent damage.

There are times when the tried-and-true Ken Burns narrative style improves the material. One of Burns’ most useful tools has always been digression, which he uses to introduce a new character or concept before taking a few minutes (or longer) to explore its history and meaning. Here, that technique is most frequently applied to Ali’s biggest rivals: Sonny Liston, Joe Frazier, George Foreman, and Larry Holmes. This series gives each of these men his due, telling their stories and making it clear that with just the slightest shifts in perspective, they could be the heroes of their matches, with Ali as the heavy.

Throughout, Muhammad Ali remains clear-eyed about the contradictions of its subject. Seen one way, the legend of Ali is about a man who overcame both overt and institutionally ingrained racism to become a rich and famous icon of freedom. Seen another way, he was the handsome, shrewd, coddled darling of the establishment press—and of his wealthy, white Kentucky backers, who loved to hear him talk about how ugly, dumb, and primitive his opposition was, because it validated their own prejudices. Ali was a prodigious womanizer, yet his ex-wives were still willing to talk in this doc about how much they loved him. He was an oft-absent father whose kids (or at least the ones interviewed here) insist he was a wonderful parent. He betrayed friends like Holmes and Malcolm X, but would give the shirt off his back (plus a few hundred bucks) to strangers.

Muhammad Ali also tracks an evolution in public opinion. Thanks to his talent and charisma, Ali was one of the most famous fighters in the world before he won his first professional title; yet for many Americans back then he was the heel they loved to hate. Initially, his objection to the Vietnam War turned him (for some) from a cartoon villain to a widely despised traitor; but his persistence in court combined with a willingness to keep stepping into the ring after he’d clearly lost a step eventually wore down a lot of doubters. By the time a retired and visibly weakened Ali lit the Olympic torch at the 1996 Atlanta games, he’d become almost universally beloved.

So yes, of course: Muhammad Ali is absorbing, insightful, and easy to watch—everything one would expect from a Ken Burns production about a true American hero. In Muhammad Ali terms though, this series is closer to the mid-’70s than the mid-’60s Ali. It’s more dogged than spry. At one point in this series, the novelist Walter Mosely sticks up for Ali’s first big opponent Sonny Liston, calling him “a great American hero” who fought his way up from nothing to the championship, only to wind up becoming a relatively minor character in the very public saga of a man who was getting Life magazine photo-spreads in his early 20s. Mosely talks about Liston’s hardscrabble past, saying he was “from back there.” For a moment, hearing Mosely wax poetic about Liston, it’s hard not to think that as great as Ali was—“The Greatest,” even—that maybe this was the time to put someone in the spotlight who wasn’t already one of the 20th century’s most well-documented people.

19 Comments

For people my age, it’s hard to overstate how giant a presence Ali was. Worshiped would be an understatement.

Sort of. I remember plenty of adult uncles and cousins grousing about him in the late 1970s and rooting for Leon Spinks in 1978.

My dad was one of the people grousing, which is kind of weird looking back at it now, he was never one of the ra ra Americuh types, despised Nixon, but somehow still didn’t like that Ali refused being drafted. All the boys at school loved him though, I was indifferent, didn’t care about sports then or now. I love him now though, mostly because of his stance on Vietnam, after I found out that he wouldn’t even have to fight in Vietnam, they were just going to let him do boxing exhibitions, and he still fought the draft out of principle, he won my heart.

It was the draft and the cocky attitude that they didn’t like. Probably also the Nation of Islam stuff too although these relatives weren’t John Birchers or whatever. And it was light grousing. All of them conceded how great he was as an athlete. They just didn’t like the attitude (and the draft and the name change). I, of course, realize there’s a word for their feelings, ultimately. Me, personally, I can’t get enough Ali stories so I’m definitely watching this even though I watched all those other documentaries plus a bunch of books. I am the furthest thing from a sports fan but I’m a MASSIVE sports narrative fan.

Certain journalists and public figures insisted on referring to Ali by his birth name for years after he’d changed it. They absolutely meant that as an insult.

It’s funny that that was mostly the pre-Boomer generations, even Trump nuts have a decent amount of respect for him.

Dick Schaap and Howard Cosell were the first to respect the name change.

“Listening to Keith David talk for seven hours” is a pretty good selling point on its own. Although hopefully he can really use his instrument, I tried watching the Hemingway documentary and Peter Coyote was so damn muted and soporific I fell asleep 15 minutes in.

“By the time a retired and visibly weakened Ali lit the Olympic torch at the 1996 Atlanta games, he’d become almost universally beloved.”Having seen the above mentioned HBO documentary about the Thrilla’ in Manila, “almost” everyone is just right. Frazier’s reaction in that documentary to Ali lighting the Olympic fire while shaking from Parkinsons is both chilling and profound, and says a lot about the human condition.

Honest question here – how does he get a pass for impregnating a 16-year old at the age of 32, let alone get an airport named after him?

When We Were Kings is so good I usually watch it at least once a year, and I’m not much of a boxing fan.

I think Burns does slightly better with grand sweeping subjects. I think his Vietnam and Country Music are among his best works, while Jackie Robinson and Hemingway are good but stand out less among his filmography. The Roosevelt one was a weird in between since its both three personal stories yet stretches for over a century, that one was I feel his best take on individual stories. I’m sure Ali will still be good, better then his early works. Seriously watch Civil War now, it’s aged quite poorly.

New York: A Documentary Film by younger brother Ric Burns is amazingly good. Just really, really, really great.

It absolutely is. It’s free on Amazon and worth seeing alone for the Robert Moses episode.

why has “Civil War” aged poorly?

Because of Shelby Foote. He gets over 40 minutes of speaking time, far more then anyone else. He spends that time waxing about how awesome Nathan Bedford Forrest was and that the war was about states rights. Also the Confederacy was noble. There are other problems including a lack of historians being consulted, reconstruction mostly being ignored and too much detail given to battles instead of the big picture, but Foote and his Lost Cause beliefs are a massive problem.

what are better Civil War documentaries to seek out?

Liston really is a fascinating – and tragic, and weird – story. I wonder how perceptions of him today would be different if he’d lived to fight Frazier. His performances after the Ali fights (15-1 with 12 knockouts, and 1 was an unexpected knockout in a fight he was winning) would certainly have made him hard to ignore forever, despite his advanced age; and if the fight had happened, given his power and insane reach you’d have to suspect it might have gone the way of Foreman-Frazier (or indeed Liston-Patterson). It would at least have made him a part of that Frazier-Foreman-Ali story people remember, instead of being seen as only a prelude to that era.Between 1954 and 1969, the guy went 15 years in which he only lost to Muhammed Ali (twice) – and both of those fights were bizarre (there’s suspicions he threw one or both of them). Ali himself said that the first fight with Liston was the hardest of his career – and that was against an undertrained Liston with only one working arm. The man is greatly underestimated in the modern era.

I’m not going to dispute Liston’s greatness but after the Ali fights he had mostly given up on taking his fights seriously he only fought bums in that period. The only opponents who could be considered contenders in that period were were Leotis Martin who knocked Sonny out in 1969 and Chuck Wepner who lost due to cuts. Frazier would have destroyed him by the time they could have fought in 68 or 69.