Netflix’s Challenger: The Final Flight scrutinizes one of NASA’s—and America’s—worst moments

TV Reviews Pre-Air

In the early days of NASA, the public and the press spent a lot of time micro-analyzing the organization’s failures. Why did our rockets keep blowing up on the launch pad? Why did the Soviet Union keep beating us to major space-exploration milestones? And so on and so on, year after year.

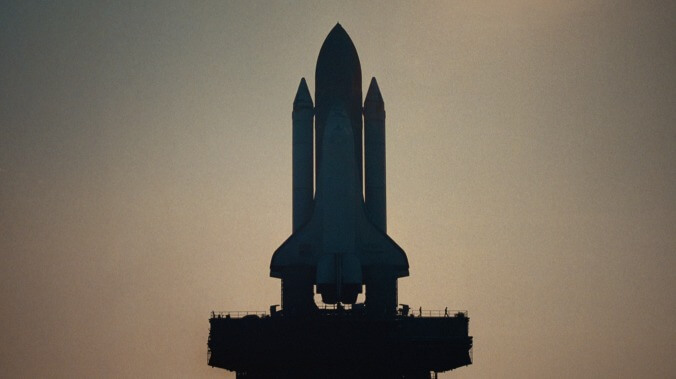

Then NASA went on a hot streak. The Mercury program. Gemini. Apollo. The space shuttles. For about 25 years, most American space flights went off without a hitch, and even the few that went awry mostly ended with safe landings and lessons learned. The processes ran so smoothly that the citizenry largely stopped paying attention to what their tax dollars were paying for—except to complain occasionally that our money might be better spent here on Earth. And then—as Netflix’s new four-part docuseries Challenger: The Final Flight covers in engrossing detail—one of NASA’s spacecrafts exploded, devastating and unnerving a nation that hadn’t seen bad news like this in a long time.

For many American millennials, the defining traumatic event of their youth is the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001. For a lot of Baby Boomers, it’s the assassination of President John F. Kennedy. For Zoomers? Well, it’ll probably be what’s happening in this country right now, with the pandemic. But for Gen-Xers—who grew up in an era when war was largely theoretical, and where most political debates centered on tax rates—the big, terrifying “Where were you?” moment was the Challenger explosion.

On January 28, 1986—a day when a lot of American kids were in school and watching the launch—the space shuttle Challenger blew up 73 seconds after liftoff, killing everyone aboard. One of those crew members was Christa McAuliffe, who’d been selected to be the first teacher in space, at a time when NASA was trying to reignite the public’s interest in their business by diversifying their astronaut pool. Instead, McAuliffe’s participation meant that a larger number of people witnessed a tragedy unfold, live on television.

The Final Flight looks back at the circumstances surrounding the explosion: what was off-kilter about the culture at NASA in the years leading up to the disaster; the bright hope represented by this particular crew; and how the space program changed afterward. Co-directors Steven Leckart and Daniel Junge have plenty of archival news footage to drawn on—much of it as raw and emotional now as it was when it aired 34 years ago—which they supplement with a few dramatic reenactments, and plenty of tear-filled interviews with some of the people who witnessed this history up close.

What emerges—especially in the fourth chapter—is the story of a noble American institution that by 1986 had gotten into the habit of cutting corners, assuming that everything would work out okay, as it nearly always had before. For the most part, there was nothing insidious happening at NASA before the disaster. It was more that some well-meaning people had lost perspective, and had grown overly complacent. That said, the most alarming interview in part four is with one of the men who green-lit the Challenger flight, who acknowledges the multiple warnings back then of a possible catastrophic equipment failure but says he’d still make the same call today, because he considers the rewards of the space program worth recklessly risking human lives. (For anyone wondering why a documentary about something that happened in the ’80s is still relevant today… well, the level of callousness in that comment should give a good reason, given that it’s more than a little reminiscent of our recent pandemic debates.)

The post-mortem passages of The Final Flight represent the series at its best. Like nearly every TV docuseries these days, this one is overlong, and broken up into too many parts. It could easily have been two tightly packed hourlong episodes, rather than three fairly shapeless ones that run around 40 minutes each followed by an excellent concluding one that runs around 50. But that last chapter is so moving—and at times enraging—that it justifies the whole project.

The first three episodes do zip by fairly quickly, and they do have their moments. Their primary purpose isn’t just to lay the groundwork for what went wrong on January 28, but to explain more about what and who was lost when the Challenger exploded. Leckart and Junge give each crew member some screen-time, documenting their past accomplishments and letting their loved ones talk about their personal lives. A lot of the astronauts on this mission emerged from an overdue initiative to bring more women and racial and ethnic minorities into the fold, which means that this documentary tells the inspiring stories that the crew members themselves might’ve told, had they lived.

Naturally, much of the “up close and personal” material is about McAuliffe. As NASA began considering sending civilians into space, the public debated who it should be. A writer? A celebrity? A journalist? (Among the names floated, according to the documentary: Tom Wolfe, Walter Cronkite, John Denver, and Big Bird.) When the decision was made to send a teacher, McAuliffe joined a group of contenders at space camp, where she quickly became a favorite not just of her instructors, but of her classmates. Her enthusiasm for the mission—and her genuine love for teaching—were infectious.

The earlier, looser episodes allow for more of an unabashed wallow in the particulars of the era, from the cringe-inducing (like Tom Brokaw asking Challenger crew-member Judith Resnik if anyone had ever suggested she was too cute to be an astronaut) to the retroactively ironic (like Jerry Seinfeld joking on The Tonight Show that the only way to interest people in the space program again would be to draft ordinary people who didn’t want to go). The Final Flight captures how much the space shuttle program’s first era shadowed 1980s culture, from the multiple congratulatory statements and phone calls from Ronald Reagan to the guest appearances by the likes of Steven Spielberg and Peter Billingsley at launches.

But Billingsley’s presence here—in older footage and in new interviews—also provides a useful pivot-point into episode four’s more substantive material. It’s harrowing to hear Billingsley describe what it was like to witness the Challenger explosion in person, standing in a crowd of people who weren’t sure what they were seeing until they heard the creepily detached voices of NASA Mission Control saying, “Obviously a major malfunction,” and, “The vehicle has exploded.” It’s hard not to be overwhelmed by the images from that day—the weeping spectators, the contrail lingering in the sky—and by the testimony of family members describing their still-painful feelings of loss. (Try not to break down when one of the astronauts’ wives talks about disappearing into the bedroom to hug his clothes, and then finding the Valentine’s Day card he was planning to give her when he came home.)

The sentimentality quickly shifts to tension and outrage as The Final Flight gets to what happened next, which involved NASA stonewalling the press, the media doing their own analyses of the footage, President Reagan convening an exploratory commission (and giving its head the command, “Don’t embarrass NASA”), and a few unruly scientists (including the late, great Richard Feynman) slipping past the gatekeepers to say what needed to be said, about the agency’s increasing preferences for cost-cutting and upping the number of missions over basic safety protocols. The series ends with an impressive flourish.

So sure, The Final Flight could be a lot more focused. But Leckart and Junge ultimately have the goods, and they do deliver. Their final half-hour in particular is incredibly dramatic, echoing a lot of the discussions we’re still having—all about whether it’s better to be honest with the American people, or to preserve our myths and heroes.

108 Comments

This will be interesting. Challenger had a chapter in Christian Morel’s excellent little book on “Absurd decisions”, where he studied contexts that favor systemic mistakes and lead to ridiculous situations or catastrophes that would seem obvious to prevent in retrospect.

You might like Systemantics.

8 year old me could not process this thing. I wanted to be an astronaut and we got to watch the launch in school. It kinda fucked me up and made me act out in weird ways, like I became obsessed with terrible jokes my uncle made about the disaster. It landed me in kids therapy for a few years.

From personal experience I’d say that most kids (well, most boys) like a good disaster joke, until one occurs that’s a bit too close to home, after which they never regain their taste for them.

Well my mistake was telling them to my teacher. She did not appreciate them

Damn, that would not have gone over well with my teacher either…

I assume the famous “NASA’s new acronym” one was amongst your setlist? It’s the only one I remember.

Oh I have NOT heard this one. Please you’ve GOT to tell me, unless it is so beyond the pale that it might get flagged.

At the risk of firing up the hankie wringers, Need Another Seven Astronauts.

DAYUM. You did not disappoint.

I literally haven’t thought of that joke in over 30 years. And I absolutely spread it around at the time.

“No, Christa, not the *red* button!”“How many astronauts can you fit in a Volkswagen?” was another popular one.

The one that floated around MY school of Young Sociopaths was, “Why didn’t McAuliffe take a shower before launch?”There were more, but I’ve thankfully got a terrible memory.

I think we had a version of that one too, if it’s what I think it is.

“All of them” is the answer to that one, right?

11. Two in the front seat, two in the back seat, and 7 in the ashtray.

OK that’s worse. Thanks for the reminder, been quite a while.

In addition to NASA, I just remember the dandruff one…

Those are the only two I remember.

“How many astronauts can you fit in a Volkswagen?” was another popular one. That was a repurposed joke. The original wasn’t astronauts, and the Volkswagen was not coincidental.

Yeah, I heard that one too.

I remember that one. You don’t remember the one involving dandruff shampoo . . . ?

Not at all.

The one I remember to this day is “What color were the Challengers astronauts’ eyes?”“Red, White, and Blew”That was told to me by my pastor’s son. Kids have a sick sense of humor. I always forget the NASA one. I’m also horrible with acronyms, so go figure. I was 10 and the preachers kid was 9.

Let’s not forget that it was the Senator from Utah that killed those astronauts. The original plan was for the solid fuel boosters to be built on-site without the joints that ultimately failed. NASA was given the choice – use that booster or close the entire agency.

And Reagan insisting that the Shuttle program “show a profit” and launch whether it was ready to or not.

By 1986 I’m pretty sure NASA had more or less given up much hope that the shuttle program could pay for itself. It could not meet the demand of carrying commercial payloads into space frequently and cost effectively enough. As I recall, other nations, particularly the European Space Agency, were making major inroads by launching satellites more cheaply and reliably using disposable, unmanned rockets. The shuttle being taken out of commission for a year after this disaster more or less sealed that deal.Still, they hadn’t given up on the concept that the shuttle would render space travel “routine.” It’s also important to remember that at this point the USSR was really developing its Mir space station program, and the U.S. was starting to look like we were resting on our laurels, still boasting about having gotten to the moon first some 17 years earlier

Our biggest mistake was abandoning Apollo for that blasted shuttle program. And meanwhile the Russians have continued to use a variant of the Soyuz craft without incident since 1970. And the new space craft that NASA is developing now is just a beefed up version of the old Apollo craft. We’ve gone in a big circle.

The problem with the shuttle program was that it wasn’t supposed to be a shuttle program. It was supposed to “shuttle” astronauts to a space station that was never built. So instead of it just being a space jitney, it BECAME the mission.

The worst thing about the shuttle by far was the decision to side mount it on the boosters, rather than on its top. Top mounted crew vehicles are far safer because you can have launch escape towers. You can’t do that on a side mounted orbiter, nor can you safely bail out or eject until SRB separation. Unlike the other manned space programs, that ALL had means of safely aborting from launch to orbit, the Space Shuttle had NO effective means of escape for the first 2 and a half minutes. NASA willfully conceded the safety of its people.

So instead of it just being a space jitney, it BECAME the mission.Well, and that idea, “space jitney” hits upon the other major flaw of the space shuttle concept (besides being a space bridge to nowhere). When you think of a terrestrial transportation shuttle, what you’re usually talking about is something uncomplicated, reliable, and economical. It is much, much cheaper and easier to have a van that drives people from an airport or car park to a hotel or convention center than to build something like a people mover or a monorail.But the space shuttle was fiendishly complicated (some liked to describe it as the most complicated machine ever built), not terribly reliable (hence the repeated launch delays and the pressure to launch which lead to the Challenger tragedy), and not at all economical. In other words, it wasn’t anything like a shuttle.

We’ve gone in a big circle.That’s how orbital missions work.

I cast thee out!

So much about the space program is absurd and reflects our pork barrel approach to spend. Why else do you have mission control and the space center in freaking Houston, and the actual launch complex in the Cape? The old school astronauts actually used to commute back and forth via T-38 trainer jets. To have a the rockets produced in a landlocked state a whole continent away from the delivery location was utterly moronic and as you noted, introduced the fatal flaw to begin with.

As much as I hate what used to be Morton Thiokol, its actually a good idea to keep solid rocket motor development someplace uninhabited like the Utah desert.

Good for testing, but a nightmare as far as delivery. When you’ve got such a critical piece of equipment as the SRB, it’s never a good idea to start altering the design because there’s no means of transporting the assembled booster otherwise.

Whilst I’m in agreement with the whole weird Houston/Cape Canaveral Mission Control/Launch Control gap , I’m not entirely convinced that the rocket production in Utah is a result of pork-barreling. My guess is that over the course of the Cold War, companies in Utah and neighbouring states had already been producing an absolute shitload of large rockets that were instead stored locally in silos for a different purpose.

I was in eighth grade when the shuttle exploded. I was in the library for something else…and watched on a huge TV on a rollaway cart with a few other teachers and librarians.I’m ashamed to admit that I walked away quickly, eager to deliver this bit of grim news back to my class. I felt like I was carrying some valuable secret, that no one else knew, only I did.

I suspect a lot of kids at that age (myself included) would do the same.

Oh god SECONDS later I heard the first joke about how we knew she had dandruff.

Is your name Todd Sullivan?

There’s this great myth out there that children always react to sad news with fear, sadness, and confusion. Nobody in my class cried because of this. Nobody. Naturally, as most little boys are all sociopaths, we immediately began playing “Challenger” at recess, dreaming up new inventive ways for the shuttle to blow up and kill everybody again.Because that’s the thing about kids: They have no real sense of their own mortality. Death isn’t a concept they can really wrap their heads around, so they don’t have the same feelings about it as adults. Yet we seem determined to project our emotions onto them. Sort of like how we do it with our pets.

Not to mention people at school (I was a high schooler) making grim jokes like “What does NASA stand for? Need Another Seven Astronauts.”

I was a bit older, and was more stunned than anything. “Did that really just happen?” My science teacher had applied to be in McCauliff’s chair, and even though she didn’t make the first cut was pretty severely shaken by this.

I was in 10th grade chemistry lab when a kid stuck his head in the window and said “the space shuttle blew up.” My teacher let me leave to go to the AV room where they were showing live footage of the debris falling into the sea. I think it was only one day later when somebody at lunch asked me “What does NASA stand for?”

I was also in 10th grade Chemistry when this happened. I remember hearing about it during the day at school, but it not really sinking in until I got home and saw the footage on the news. Seeing it for myself and hearing the coverage, including the analysis of the footage by the news outlets in the days following, are what drove home to me how tragic it was.

I was an elementary teacher on cafeteria duty, and I remember the student who rushed up to tell me what had happened. I think excitement (of a kind) is normal for kids when something like this happens. We don’t always feel the full emotional impact when we’re kids like we do when we’re adults.

If you were in journalism you wouldn’t feel ashamed, you’d be proud of the head start. (( Can only backfire if they’re in journalism, can only backfire if they’re in journalism . . . ))

I was in 10th grade. I was in biology and it was the last clase before lunch. Everyone was unruly and loud waiting for the bell to ring. I heard an announcement over the intercom, but I couldn’t hear what it was. None of us could. (I don’t think anyone in our high school was watching, although I’m sure the connected junior high was.) When the bell rang and I walked into the hall, it was so quiet. It was never quiet in the hall, but especially not right after 3rd hour and just before lunch. I asked someone what was going on and they told me.To this day, it makes me tear up to think about it. It was so awful.

I was 23 when it happened, and that was the first time I felt disgust over the TV networks and their coverage of events.I’ll never forget the cameras zooming in on the grandstand after the explosion to capture the anguish in the faces of the attending families and friends of the astronauts.Fuck those ghouls.

The weirdest part about the Challenger explosion is that there were talks about bringing Big Bird on the Challenger on what would end up being its final mission. Here’s what Carol Spinney had to say about it:I once got a letter from Nasa, asking if I would be willing to join a mission to orbit the Earth as Big Bird, to encourage kids to get interested in space. There wasn’t enough room for the puppet in the end, and I was replaced by a teacher. In 1986, we took a break from filming to watch takeoff, and we all saw the ship blow apart.

This was tragic enough as it was – can you imagine how it would have been if goddamn Big Bird had literally been killed? Jesus.

This bit of trivia is something I have enjoyed sharing way too many times since I learned it earlier.

awful, 43-yr old me recalls this so clearly. My 4th grade teacher was apparently a finalist in this teacher search- she’d met/knew McAuliffe and therefore our entire school was in an assembly watching (on 3 or 4 old tvs).I recall the moments of confusion, when we all watched wondering what was happening, and then a teacher running out of the room in tears kind of led us to realize what had occurred. At least 2 of my teachers went on leave after, for the memorial services, as they’d become friendly w/ her at “camp” during the process.To this day I’ve always said it was my generations JFK moment. Later generations then had 9/11, and now, COVID.awful.

Judy Resnick went to the same high school I would start at two years later, and although she didn’t go to the jr. high I was at at the time (it was a newer school), most of my teachers had taught her. They were pretty fucked up about it. Five years before, our 2nd grade class had had a conference call with her. I don’t remember it very well, but I do recall it got set up because one of my teachers was her cousin.We were out of school that morning because, I shit you not, it was so cold that several of the pipes in the school had burst.

Was she too cute to go to your junior high?

My Physics teacher was the state alternate for Teacher In Space and he got called to make a statement by the local radio station – he came back into the classroom to tell us what had happened, and only then did they turn on the TV.

Thank fuck they didn’t send Big Bird up there!

I was in school when it happened, in 8th grade, I don’t really remember anything in particular happening in my school, I don’t remember class being interrupted. I think there was an announcement over the PA? I DO however, remember when Reagan was shot, and classes being interrupted for that.

I was in college. I was still very affected My memory says that this was one of several “technological failures” around that time, and that my predominant feeling was that things were falling apart. My brother, 12 years older, was a huge NASA fanboy, and to this day he remains a firm believer in the power of technology to solve most problems. I’m almost completely on the other side.

“My memory says that this was one of several “technological failures” around that time” Well, within a few years, there was the Union Carbide Bophal disaster, Challenger, and Chernobyl. We can throw in the Mexico City earthquake if you want get naturally disastrous. What a time to be alive.

The big one for me and the community I grew up in was the Piper Alpha disaster in ‘88. My father worked offshore in the North Sea at the time and as my parents were divorced and I was only 10 years old, I didn’t always know what platform he was on or whether he was away at work or not. I woke up that morning to the footage on breakfast news of a rig in flames and immediately freaked out fearing the worst. Fortunately dad wasn’t based on the Piper at the time. He’d worked on it in the past, though and the older brother of the girl who used to babysit me unfortunately perished in the disaster. The subsequent investigations revealed that -like Challenger- it was a combination of a number of all-to-common unsafe behaviours and practices, poor design and bad luck giving rise to catastrophe.

*I should really have proof-read my comment. I’m missing a very important ‘however’. Probably shouldn’t be trying to comment on here at the same time as watching the aforementioned documentary.

I was 9 when the Challenger disaster happened, and I watched the whole thing unfold sitting in my 3rd grade class. I was going to law school in Washington DC when 9/11 happened. I am not ashamed to say that I still often feel like crying when I think about both.I will def. watch this documentary, though I am sure it will dredge up a lot of emotions.

I someone conflate it with the Colombia disaster, which was on TV in the background when I was waiting to go to my grandfather’s funeral. I do not have positive associations with the shuttle program.

*sometimes*

wtf?

One of the defining moments of my 11-year-old life was watching this unfold on the ubiquitous TV strapped to the rolling metal cart with the rest of my classmates. As the story unfolded afterward in what retrospectively feels like agonizing slowness, I came to understand that corruption in government was a thing, and that cutting corners costs lives. I’d point to this as the starting point of my disillusionment in the rah-rah bullshit of patriotism and the myth that government only has best intentions.

My late mother talked about it in the same way people talk about 9/11. Horribly traumatic, what a goddamn shame. Although not to laugh, but John Denver almost getting picked is some Final Destination stuff, seeing how he died in an aircraft accident a few years later.

Denver was very excited to go and even passed all of the physical exams. After it exploded, he wrote the song Flying For Me in their honor.

I believe it came down to him or McAuliffe. I would be beyond traumatized if I was Denver. I’ve heard that song and its quite moving.

He got to dive with Cousteau and wrote a song about it, so he had enough honors.

I unabashedly love John Denver, and cried when he died. He is only one of three celebs I’ve ever cared enough about to cry for.

The contempt dripping from Richard Feynman as he revealed the o-ring flaw is really something. We need more like him.

I hope this covers the great story where Feynman was getting the runaround about the O rings working in cold weather, so he just demonstrated at a hearing how he squeezed one with a clamp and dropped it in ice water to show how they didn’t work.

http://www.feynman.com/science/the-challenger-disaster/Of course, Congress barely holds hearings anymore, so this kind of thing is unlikely to happen now.

It was so simple and so amazing.

That’s just one of the best things. He effectively made his point the same way a primary school teacher would – with a simple demonstration which proved a much greater point.Feynman was, if nothing else, an incredible communicator.

I remember that. I remember reading about it. I remember thinking “How can a bunch of well-paid, professional people have missed something so GLARINGLY obvious? How could they have ignored something so hugely important and problematic?”Of course, it didn’t take long before I learned the answer, one that is at the heart so many god-awful things in today’s world: “Because money.”

He really had a moment going there at the time. Obviously he was a great physicist and Nobel Laureate and everything, but he had just published his famous memoir Surely you’re joking, Mr. Feynman! the year before and people who had no idea of how quantum physics worked knew him as an eccentric scientist. Sadly, he died in 1988, so he missed out on much of the (still ongoing to this day) popularity of him as a celebrity.

I was only 2 when the Challenger accident occurred, so most of my memories of it are likely from long after the fact. However, my parents were both educators, and my dad was particularly excited about the prospect of a teacher going into space. His science class exchanged letters with McAuliffe’s class and followed the preparation for the mission closely. It was really devastating and hit him hard.Many years later, when I was in engineering school, the Challenger accident was taught as a case study in one of my classes as an example of the dangers of “groupthink” and cascading errors in complex systems.

Oh yes, the disaster is a master class in so many things going wrong. Few realize just how close that mission was to succeeding, in spite of all the fuckups. If it hadn’t been for an abnormal windshear that hit the shuttle, and broke a temporary oxide seal that formed when the O-rings burned through, the mission would’ve likely held on until staging. Or if the seal had failed just a few degrees clockwise or counterclockwise, you would’ve likely had an abort to orbit due to a loss of thrust from the failing booster, but at least, the crew and shuttle would’ve survived. Everything that could possible have gone wrong in the worst way did on that day.

The analogy of the holes in a block of Swiss cheese lining up is a very popular one in my industry (Oil and Gas)

This is one area of history I’ve studied extensively, so AMA.

But what that guy said, about his decision to launch, even now, knowing what he knows, is just galling. The greatest failure of the Challenge wasn’t the flawed booster design, or the O-rings, it was the engineering culture.

When the booster rockets were first build and tested, it was clear there was a flaw in the design. The boosters were built in pieces, and assembled with rubber O-rings in between to form a gastight seal. But what they found was the rocket vibrated badly, and would actually flex and create gaps through which hot gases could leak. But what they found was the O-ring would expand and fill the gap. The fact that the joints flexed at all was a dangerous flaw, but because the O-ring functioned (albeit in an unintended fashion) they kept the design, and they even normalized what was flawed behavior. They called the phenomenon “extrusion.” Time and time again, they changed their own engineering parameters, as design features deviated more and more, so they could stay within the margins of safety. When gasses severely damaged one O-ring during several flights, they did nothing, because the secondary O-ring still kept the seal in tact. They relied upon a failsafe backup, which was a total violation of safety procedure, which held that one could NOT fly if reliant upon a failsafe. The failsafe was only there as a last resort. Not as a means to ensure a mission proceed. The moment those O-rings started to show signs of damage in flight, the flights should’ve been grounded for a redesign.Instead, they took a flawed understanding of the term “safety factor” and took a defective piece of mission gear, and dubbed it safe to a factor of three, that is, three times beyond it’s normal use load (because the O-rings only burned through one third of a way). To use an analogy employed by Richard Feynman, it was akin to to calling a bridge safe, because it only cracked one third of the way through it’s width when a load was applied. The Challenger disaster was a gross dereliction of every standard and practice of safety in aerospace, one that NASA was not fully held to account for, which led to an effective repetition of the mistakes in 2003 when Columbia disintegrated in Earth’s atmosphere. The conduct was criminal.

I’d suspect you’re much more knowledgeable about this than I am but yeah, that was my thought as well: to have someone say they’d do it again just made me shudder thinking about that idea of parameters that seemed almost abstract given how readily they were shifted and contorted. Yeesh.

For me, reading the critiques of NASA by the many tremendous Gemini and Apollo era engineers and astronauts who’d been pushed out of the program – often by politics – before and during the Shuttle Era has been the most eye opening. Some of the oral histories are just brutal.As much as it’s tremendously uneven and overall I’d say it’s a disappointment, I’ve thought one of the things For All Mankind does well is to project a lot of the later problems at NASA back into the Apollo era and eliminate the gloss of luck that saved a lot of the program in those years – along with adding in the baseline competence of that era that did so as well.

It has always bothered me that only Christa McAuliffe gets mentioned in 90% of the articles about the Challenger explosion. There were 6 other people that lost their lives due to gross incompetence.

I remember my high school calc teacher wheeling a TV into our room mid-class without a word to show us what was unfolding post-explosion and how grimly quiet it was in the class. Even if it weren’t mid-pandemic and I weren’t looking for anything mindless and funny to distract away from life, I still am not sure I could watch this, just too sad to see so many hopes come crashing down. (and don’t even get me started on the realization years later that some of the astronauts were still alive when they hit the water)

Yeah, I’ll give it a shot, but I’m not laying odds I’ll get it finished.

“ (and don’t even get me started on the realization years later that some of the astronauts were still alive when they hit the water)“I remember finding out about this possibility in the mid-90’s and it floored me. Cannot even imagine. You get no stars for reminding me of this.

I was in my second year of university. I was walking to class (Psych 251, Personality) with my friend Dee who I had a rather serious thing for…. Anyway, we were on our way to class in the student centre and people were watching the launch on TV. She asked what it was and I said ‘oh just another shuttle launch, we have to get to class anyway’. I got home that evening and my Dad said ‘did you see the shuttle thing?’Dad had a way with understatement, on 9/11 his email to me was ‘have you seen this plane shit?’

Almost the same story – I was going to a community college at the time, and after watching the initial liftoff at the Student Center, I left and walked to another part of the campus; if I had stayed for 30 seconds longer I would have seen it happen. Instead, by the time I got to the other building they were already showing replays of the liftoff and the explosion.The one thing that sticks with me though was a week later when I was repairing my car in the driveway and listening to the radio, a local station held a minute of silence in their memory – and then immediately followed it up by playing Major Tom.

Sorry, I should know better – not Major Tom, it’s Space Oddity

“Sorry, I should know better – not Major Tom, it’s Space Oddity”Now that really would have been inappropriate

Holy crap, I totally forgot that song/video.

I was 10, home sick from school that morning with the flu and watched it all happen live on tv with my Mom.

And you know, we’re going to do it again to send humans to Mars. We’ve already rationalized the likelihood they will die there, if they even get there. If we want to branch out we could achieve so much more if we learned to exist under our own H2O blanket here on earth, where there is oxygen, food,ability to harvest more food, radiation protection, crucial gravity and accessibility to land and services. Mars is literally poisonous to us, and every single thing we need to live must be trucked there OR YOU DIE. Water, air, food, radiation protection, and a fault in any one of them AND YOU DIE.

I was a teenager. I had just been given the job of guitar tech the day before with the band Poison, with whom I lived.

I was in L.A., so the disaster had already happened by the time I woke up…but I remember sitting there changing guitar strings that morning while the TV played the shuttle blowing up over and over…

I was too young to witness Challenger’s explosion but I grew up wanting to be an astronaut in the shadow of the event and its aftermath. When I went to America in the mid-1990s the great joy of the trip was getting to go to Cape Canaveral and see the space centre. The Shuttle Atlantis was on the launchpad at the time and it was so exciting.Unfortunately my dream never came close to coming true because I had no aptitude for math or science and, more pertinently, my physical disability more or less precludes me from anything even approaching it.Still, seeing that footage of the shuttle exploding, the knowledge that some of the astronauts survived the explosion and were likely still alive at the point of the cabin falling and hitting the water never fails to make me feel emotional.In 2003 I remember watching the destruction of Columbia and feeling deeply distressed.

I was in second grade – out a recess, and when we came in, our teacher was crying. I can’t remember if we watched the footage at school – I’m thinking we didn’t – but it was a very somber day. NASA was a big deal back then for a lot of kids – not so much any more. I remember hearing about the space program all the time in school, and on the news. I’m looking forward to watching this.

Anyone who wants to dive deep into what went wrong with the Shuttle programme should get a copy of ‘The Challenger Launch Decision: Risky Technology, Culture and Deviance at NASA’ by Diane Vaughan. What became clear in retrospect, wasn’t just that the Shuttle had been fatally compromised by conflicting requirements and cuts in its development budget; but also that budget pressures and an ever-increasing launch cadence at Kennedy were inevitably pushing the Shuttle towards disaster and there was no effective way for people to push back.But can it really be nearly 35 years since that dreadful day when I remember the BBC breaking into programmes with an initial report that there had been some sort of fire at Kennedy?

I was in 5th grade, 10 years old, and in a small private religious school. We had all been following McCauliff since she was chosen, especially since my mom was a teacher in my school (fun times…). We all gathered around the TV to watch the liftoff and we were all cheering, and then. Silence. I’m fairly certain that it was decided to call it a half day at school.I had just started to read sci-fi, and it just made it all that much more real. The Columbia disaster was the beginning of the end for the shuttle missions and project in general. I watched that live with my neighbor, and after we couldn’t take it anymore, at least discovered a great movie with Steve McQueen and Dustin Hoffman called Papillion.

I was a senior in high school, and was watching from home when the Challenger exploded. Don’t recall why I was wasn’t at school—possibly it was one of those “teacher workdays.” But I remember thinking that, in retrospect, we’d been so damned lucky up till that point. We’d never pictured something like this happening, but we should have.On a slightly related note: I cannot overemphasize what a complete failure of nerve & vision the entire Space Shuttle program was. To walk on the moon, and then to pull back and spend the foreseeable future futzing around in low Earth orbit by design … all these decades later, it still makes me see red.

Classic definition of “too soon” for me. It’s been over 30 years, but I don’t think I can bring myself to watch this. It’s still too damn depressing.

I was in college and heard about it in the hallway while walking to class. Some frat boys were talking about how cool the explosion looked. They’re probably CEOs for aerospace companies now.

I was in second grade, and extremely into space and the space shuttle (as a kindergartener I’d memorized the countdown and launch sequence that the mission control guy narrated during launch). Watching this live on TV was…unpleasant.

I’m watching it now, in the middle of episode 3. It’s still gripping, even though it’s an event I remember, and something I’ve already read up on/seen documentaries about. It’s very interesting to me to see all of the former NASA/Morton Thiokol employees whose employment dates stop abruptly at 1986.

I was home sick from school and watching a game show when the news cut in with the announcement. My strongest memory is them showing the footage of McAuliffe’s parents watching the launch and subsequent explosion. I want to say they replayed it more than once. I was young but I still recognized how ghoulish it was to show that.

I can’t recommend Retro Report’s episode on the Challenger Explosion enough. I think it won an award.

Even back in the USSR, I remember hearing about the Challenger tragedy. I was 7, but I still remember this being reported on TV.Then, in 2003, an Israeli astronaut Iran Ramon flew on Columbia, and a lot of us here were watching the landing on TV, and seeing the disaster live. A few years ago I was at a panel about Columbia that my university organized, there were a few NASA people and Ilan Ramon’s wife. This was very emotional. Basically, NASA knew about the insulation problem, knew the shuttle would probably not return safely and didn’t tell the astronauts because there was little chance of any rescue operation to succeed. Nothing much changed at NASA since the Challenger disaster.