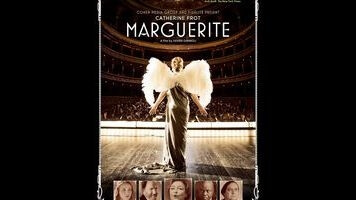

There is perhaps no artistic milieu that’s been more heavily romanticized than Paris between the wars, a period when surrealism was in full swing and the Lost Generation was writing (and drinking) itself into history. The French film Marguerite, which takes place in 1921 amid both high-society soirees and underground bohemian revels, is a well-appointed period piece that nonetheless has no time for Midnight In Paris–style nostalgia. Even the avant-garde strivers on the sidelines of director Xavier Giannoli’s diverting sixth feature overflow with greedy self-interest. But no one here has less talent than the title character (Catherine Frot), a fantastically rich baroness who fancies herself an opera star—and has no idea how awful her singing actually sounds.

During a well-staged opening scene, conveyed from the outside-looking-in perspective of critic Lucien Beaumont (Sylvain Dieuaide) and recent conservatory graduate Hazel (Christa Théret), the mysterious Marguerite makes her grande-dame entrance at a charity concert for war orphans. Looking ever so poised, her head crowned by a single peacock feather, the singer nonetheless soon has everyone in attendance wincing. If it was a botch of a painting, they could simply look away and be done with it, but even in the supposed refuge of the next room her high-pitched warbling is murder on the eardrums. The members of the Amadeus Club (Marguerite’s exclusive audience) put up with the pain simply because their patron is so rich—though she has no clue that’s the case. In addition to their polite words, Marguerite’s husband, Georges (André Marcon), and her household’s head butler, Madelbos (Denis Mpunga), have rigged it so that she only gets positive reinforcement. For Madelbos, it’s a full-time job within his full-time job: He takes photographs of her in costume, removes the occasional unkind notice from the papers, and creates the illusion of an adoring public by sending her roomfuls of flowers.

The script, which Giannoli wrote with Marcia Romano, suggests that Marguerite’s taking to the stage stems from a desire to win her husband’s affection—Georges has been the beneficiary of her family fortune, but now he keeps her in a state of not-quite-blissful ignorance while he runs around with another woman. More interesting, though, is the way the Giannoli and Romano—inspired themselves by the story of real-life socialite Florence Foster Jenkins (whom Meryl Streep will play in a Stephen Frears biopic out later this year)—solicit a sort of admiration for their in-the-dark protagonist. She doesn’t quite deserve pity, though her wealth has sadly led everyone to smile and nod rather than just be honest. Shortly after receiving a put-on positive review from Lucien, Marguerite hatches the idea of a public coming-out recital, and drafts faded opera star Atos Pezzini (Michel Fau) as a voice coach. Blackmailed into taking the job, Pezzini gets a team of consultants on the payroll and advises Marguerite to camp it up, putting her in boudoir dress and directing her to put her hands all over herself, among other indignities. She might be wildly misguided, but she’s also far more fearless than she can possibly know. And doesn’t it also take a leap of faith bordering on total delusion to get even the greatest artistic endeavors off the ground in the first place?

It’s hard to imagine anyone but Frot, who won a César for playing Marguerite, at the center of this movie. The actress, in her late 50s, has a cherubic face that perfectly matches the character’s blinkered worldview, and yet her disposition isn’t all sunny—here, her eyes betray the fact that she’s always bracing for disappointment. The fairly suspenseful last act of the movie hinges on just a few changes of expression that unfold slowly across Frot’s face. Though tragic at such moments, Giannoli’s film is ultimately a comedy about a most unusual fish out of water. Marguerite—who pleads for her Georges’ attention, but is most at home carousing after-hours with Lucien, Hazel, and Pezzini—appears both too sensitive and too idealistic for that thumping bank account. And as a great talent without any talent at all, she’s also a whole century ahead of her time.