On its 60th anniversary, Billy Wilder’s The Apartment looks like an indictment of toxic masculinity

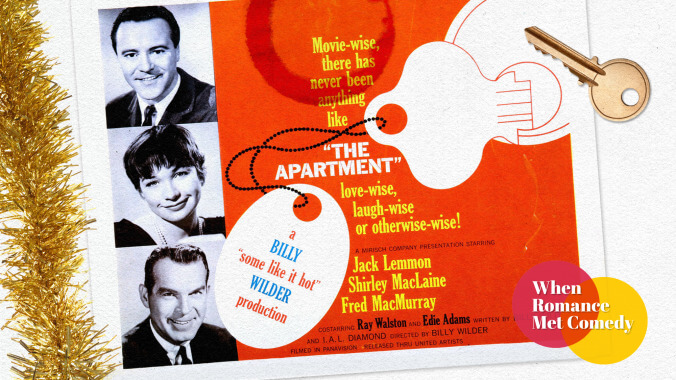

Image: Graphic: Libby McGuirePhoto: Sunset Boulevard/Corbis Film Features When Romance Met Comedy

The Apartment premiered in the summer of 1960, three years before Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique kicked off second-wave feminism and a decade before Kate Millett popularized the modern usage of the term “patriarchy.” Yet even though Billy Wilder’s classic Oscar-winning romantic dramedy didn’t have the language to describe the kind of toxic masculinity that flourishes at its central Consolidated Life Insurance company, the film offers a prescient look at the way workplace boys’ clubs can oppress both women and men. Instead of “tear down the patriarchy,” The Apartment’s rallying cry is: “Be a mensch—a human being.”

The Apartment is generally read more as a commentary on toxic corporate culture than toxic masculinity, mostly because protagonist C.C. Baxter (Jack Lemmon) isn’t a particularly patriarchal man. He takes his hat off in the elevator, he’s polite to women, and he doesn’t have the callous masculine swagger of his male higher-ups. Yet despite all that, Baxter still benefits from and uplifts patriarchy. He’s semi-begrudgingly arranged a system where he loans out his apartment for his bosses’ extramarital trysts and they agree to fast-track his promotion. Soon enough he’s got his own office and a key to the executive washroom—so long as he grants his new boss, Jeff D. Sheldrake (Fred MacMurray), use of the apartment, of course.

Wilder got the idea for the film after seeing David Lean’s 1945 melodrama Brief Encounter, in which an extramarital affair carries over into a friend’s apartment. Wilder wrote in his notes, “What about the poor schnook who has to crawl into the still-warm bed of the lovers?” By 1960, Wilder thought he could finally get the idea past the Hays Code censors. He teamed with regular writing partner I. A. L. Diamond to pen the script, creating a lovable nebbish hero who somehow wasn’t the inspiration for comedian Michael Showalter to create the term “The Baxter.”

Lemmon’s bumbling, well-meaning turn in The Apartment can be seen as the urtext for a whole generation of rom-com leading men, from Tom Hanks to Hugh Grant. Lemmon had worked with Wilder the year before in Some Like It Hot, and The Apartment solidified a creative partnership that would stretch across seven films—right up until Wilder’s final feature, 1981’s Buddy Buddy. The Apartment’s unusual comic-tragic tone proved Lemmon could handle hefty drama in addition to the light comedy he’d mastered in his earlier roles. His Oscar-nominated performance marked a turning point in his career.

For the first half of its runtime, The Apartment is sympathetic to Baxter’s plight. His inability to stand up for himself means he’s kicked out of his own bed in the middle of a wintery night when one of his bosses happens to get lucky. Meanwhile, the non-stop socializing at his apartment causes his neighbors to look down on him as an insatiable Don Juan, when in reality his only company is The Ed Sullivan Show. Baxter is lonely and put-upon, both unseen and unfairly judged. To make matters worse, he discovers that the woman Sheldrake is bringing back to his apartment is actually his office crush, plucky elevator girl Fran Kubelik (Shirley MacLaine). Nice guys, it seems, always finish last.

And then Fran tries to kill herself. It’s a dark turn for a romantic comedy, but not an entirely unexpected one for a Wilder film. The Austrian-born writer/director helped popularize the film noir genre with 1944’s Double Indemnity and curdled old Hollywood glamour into something sinister in 1950’s Sunset Boulevard. Wilder’s 1950s comedies tended to have a subversive edge too—look to the infidelity at the heart of The Seven Year Itch or the boundary-breaking drag shenanigans of Some Like It Hot. Even his feather-light rom-com Sabrina features a suicide attempt. For Wilder—who fled to Paris during the rise of the Nazi party and whose mother, grandmother, and stepfather were killed in the Holocaust—lightness seldom exists without darkness.

Fran’s suicide attempt shifts the tone of The Apartment, repositioning her, not Baxter, as its central tragic figure—the one who suffers the most under the patriarchal hierarchy that Baxter can at least sometimes benefit from. Baxter arrives in time to save Fran, enlisting his kindly neighbor Dr. Dreyfuss (Jack Kruschen, also Oscar-nominated) to pump her stomach and work off the after-effects of her sleeping pill overdose. Yet as Baxter sweetly helps the woman he loves, he’s equally focused on protecting the married Sheldrake from public scandal. Baxter just can’t accept that the man who gave him his swanky new promotion could be quite as heartless as his behavior suggests—even as Sheldrake is clearly more focused on ensuring Baxter’s silence than making sure Fran is okay.

The Apartment is at its sharpest when observing the banality of Sheldrake’s cruelty. It isn’t explicitly the story of a powerful man coercing his female subordinates, although there’s an undercurrent of that at play when we learn that Sheldrake has a long history of office affairs, including with the woman he’s dumped as a girlfriend but kept on as his silently suffering secretary (Edie Adams). The Apartment is also frank about the sexual harassment Fran experiences from skeevy executives in her elevator. But Wilder’s focus is first and foremost on Sheldrake’s subtle emotional gaslighting.

Earlier in the film, when Sheldrake asks Fran to meet him at their secret rendezvous restaurant, she’s clear-eyed about the fact that their relationship was just a summer fling while his wife and kids were away. Though she’s still heartbroken about their split, it’s nothing a new haircut and a little time won’t fix. But then Sheldrake tells her he’s planning to divorce his wife for her and he’s even visited a lawyer about it. So against her better judgment, Fran gets swept back into the affair and right into Baxter’s apartment. It’s this manipulative rekindling that proves near-fatal.

As in Double Indemnity, Wilder casts Fred MacMurray against his wholesome leading-man type, channeling his confident charisma into a morally repugnant character. (Wilder originally cast Paul Douglas in the role, but the actor died of a heart attack just before filming began.) The morning after re-seducing Fran, Sheldrake conspiratorially complains to Baxter, “You know how it is… You see a girl a couple of times a week, just for laughs, and right away she thinks you’re going to divorce your wife. I ask you, is that fair?” Baxter half-jokingly replies, “No, sir. That’s very unfair—especially to your wife.”

One of Wilder’s central tenets as a filmmaker came from his idol and mentor Ernst Lubitsch, who’d helped Wilder make a name as a Hollywood screenwriter by directing his 1939 comedy Ninotchka. As Wilder advised, “A tip from Lubitsch: Let the audience add up two plus two. They’ll love you forever.” In The Apartment, Baxter silently discovers that Fran is Sheldrake’s lover when she hands him the broken compact mirror he’d just returned to Sheldrake himself. “I like it that way,” Fran notes when Baxter comments on the fractured glass. “Makes me look the way I feel.”

Though Lemmon is its star, MacLaine is the biggest key to The Apartment’s tricky tonal balancing act. Her wry, Oscar-nominated performance locks into the sour-sweet mix Wilder is aiming for. In MacLaine’s hands, Fran is a sometimes wise, sometimes naïve young working woman caught between the old-fashioned values of the Eisenhower era and the swinging sexual revolution to come. When Sheldrake belittles her for not being a “good sport” after he confesses that he doesn’t actually plan to leave his wife, a tear-stricken Fran deadpans, “You’d think I would have learned by now. When you’re in love with a married man, you shouldn’t wear mascara.”

After the harrowing sequence in which Baxter and Dr. Dreyfuss rescue her, The Apartment settles into a surprisingly upbeat third act in which Fran and Baxter play house over a long, cozy holiday weekend. Despite the seriousness of its subject matter, The Apartment is very funny too—sometimes darkly (as when Baxter removes the razor blades from his bathroom before he lets Fran brush her teeth) and sometimes whimsically (like a scene where Baxter strains his spaghetti with a tennis racket).

In fact, The Apartment is hard to classify. It was marketed as a comedy yet shot in dramatic Cinemascope and filmed in black and white at a time when color was the preferred medium for comedies. Both choices emphasize starkness and isolation—particularly in a shot where the rows of desks in Baxter’s office seem to stretch so far they disappear into the horizon. (Wilder cleverly achieved the image using forced perspective and placing smaller desks towards the back.) Like While You Were Sleeping several decades later, The Apartment understands how painfully lonely the Christmas season can be when you don’t have anyone to spend it with.

As Baxter delights in nursing Fran back to health, he attempts to take a one-foot-in, one-foot-out approach to patriarchy. He wants to win Fran’s love without giving up any of the privileges he’s gained from the boys’ club that oppressed her in the first place. At one point he heads to Sheldrake’s office to negotiate taking Fran off his hands—never mind that Baxter hasn’t talked to her about what she wants in any of this. It’s there that Baxter finally sees firsthand the extent of Sheldrake’s cavalier cruelty.

Like many a rom-com hero, Baxter has to self-actualize before he can prove worthy of his love interest. In this case, that means realizing there’s no way to reform Consolidated Life from within. His only hope at being a mensch is to leave the whole corrupt system—including its privileges—behind, and let Fran make her own choices about who she wants to be with. Wilder and Diamond elegantly structure their screenplay so that the comedic embarrassments Baxter suffers throughout the film serve as a sort of pre-emptive karmic retribution, leaving him deserving of his eventual happy ending. As Wilder once wrote in his guide for screenwriters, “The third act must build, build, build in tempo and action until the last event, and then—that’s it. Don’t hang around.”

Despite the fact that The Apartment was a box office hit and won five of the 10 Oscars it was nominated for (including Best Picture, Best Director, and Best Original Screenplay), it’s less well known by casual film fans today. It’s overshadowed by the sheer number of masterpieces in Wilder’s filmography, plus its genre-bending tone makes it hard to figure out whether to celebrate it as a romantic comedy or a romantic drama. Revisiting it 60 years after its release, however, it’s clear The Apartment’s influence has rippled through generations of rom-coms, right down to the way When Harry Met Sally seems to directly homage its New Year’s Eve climax.

A year after Wilder delivered one of cinema’s greatest final lines in Some Like It Hot, he almost topped himself with The Apartment’s perfect four-word closer: “Shut up and deal.” The Apartment is simultaneously sweet, cynical, farcical, satirical, and incredibly earnest. That unusual mix divided critics at the time, but makes the film feel all the more timeless today—especially compared to the messy messaging of contemporaneous Doris Day/Rock Hudson comedies. In the same year Psycho turned mental health disorders into horror movie fodder, The Apartment presented an empathetic, hopeful view of Baxter and Fran’s struggles with depression and suicidal ideation. Six decades later, it remains an impressively relevant story of two cogs in a capitalistic, patriarchal machine who decide the only way to truly live a good life is to escape the old system and build a new one—even if they have to start with nothing more than a bottle of champagne and a deck of playing cards.

Next time: Long before their respective renaissances, Jennifer Lopez and Matthew McConaughey made The Wedding Planner.