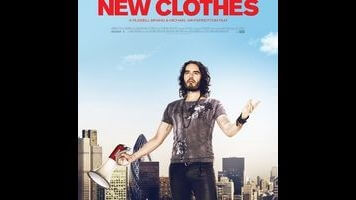

Russell Brand rants about the economy for 101 goddamn minutes in The Emperor’s New Clothes

Film Reviews Film

Want to see a cinephile run the gamut of reactions in five seconds? Explain the premise of the documentary The Emperor’s New Clothes. “It’s a Michael Winterbottom film…” [Intrigued expression.] “… with Russell Brand…” [Face falls.] “… explaining economic injustice.” [Flees room.] Alas, the only experience more enervating than hearing about The Emperor’s New Clothes is actually watching it.

Give Brand credit for some self-awareness. In the opening minutes of the documentary—after he’s recited the plot of the original Hans Christian Andersen story, in voice-over, while Winterbottom strings together images of aristocratic pomp—he looks into the camera and says, “Everything you’re going to hear about, you already know.” He then proceeds to spend the next hour and a half jumping around the recent history of banking and real estate malfeasance, explaining a little about how the rich keep getting richer at the expense of “the 99 percent.” This isn’t a thorough, systemic breakdown of the spreading crisis of economic inequality. It’s a collection of anecdotes, interviews, and Michael Moore-like public stunts, meant to underscore that something has gone very wrong—which again, as Brand acknowledges, is no big surprise.

For American audiences, the primary value of The Emperor’s New Clothes will be its largely regional focus. Brand touches on what’s happened on Wall Street over the past decade, but he’s more interested in how changes on a global scale have affected his hometown of Grays, in Essex. At its best, the documentary explores how privatization, tax cuts, and corporate franchising have turned a garden community with thriving small businesses and good social services into a gray dystopia of check-cashing shops and betting parlors, where citizens work two jobs and still can’t afford to send their kids to college. Later, Brand rails against what’s happened to Cadbury, and to British football clubs. The more specific The Emperor’s New Clothes is, the better.

More often, though, Brand will punctuate a tangent on the grand fiscal screw-job of 2008 by saying, “I don’t remember there being any consequences” for the people who caused the trouble—as though that was something impossible to check. And when he takes to the streets to try and get answers from his country’s tax-dodging, pension-robbing fat cats, he mainly ends up hassling their poor security guards (while Winterbottom cuts in shots of passersby gathering to gawk admiringly at the celebrity shouting salary figures into the faces of working men and women). The Emperor’s New Clothes makes a lot of good points about how our current warped value system has come to be seen as an unchangeable norm, rather than a relatively recent aberration. But was the best way to illuminate that message to gather 100 grade-school children in a room, assign them realistic incomes, and then ask them whether the wide disparity between the top and bottom is fair?

It doesn’t help that The Emperor’s New Clothes has some strong recent and upcoming competition. The very good financial crisis docudrama The Big Short is still expanding across the country, and the next few weeks will bring Michael Moore’s Where To Invade Next, which is a much punchier and more entertaining call to action than Brand and Winterbottom’s. It’s especially disappointing that the latter couldn’t find a way to package Brand’s shtick better, given that he’s shown in films as wide-ranging as In This World and Welcome To Sarajevo an ability to render enormous sociopolitical problems into something more human scaled.

But here, Winterbottom’s big cinematic idea is to flash “richer” or “change” onto the screen as Brand says the words, which adds pretty much nothing to anyone’s understanding of the situations being described in the film. Meanwhile, Brand attempts to clarify the difference between what a CEO and a window-cleaner makes annually by doing a quick summation of the last three centuries of human history—which is the length of time the lowest-paid worker would have to live to earn his boss’s yearly salary. When a documentary feels obliged to spend a few minutes explaining what “300 years” means, it crosses the line from simple and straightforward to condescending.