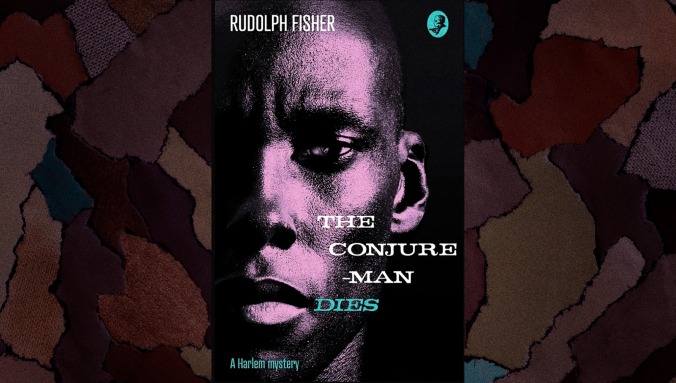

The Conjure-Man Dies—the first-known detective novel by a Black author—hints at what could have been

Aux Features Writers

Rudolph Fisher never got to experience the life of a literary luminary firsthand. A distinguished doctor by day and a creative voice of the Harlem Renaissance by night, the prolific short story writer, musician, and dramatist published just two novels before his untimely death from intestinal cancer in 1934 at the age of 37. The Conjure-Man Dies (1932), an enthralling whodunnit and Fisher’s final full-length work, could have easily functioned as the young wordsmith’s breakout effort, setting him on a path similar to those of genre giants like Agatha Christie or Chester Himes. Instead, the legacy that underscores HarperCollins’ reprint of the novel last month—as the first-known detective novel penned by an African American author—is a largely posthumous one. The witty thriller, entombed in humor and the spirit of Prohibition-era Harlem, has become a testament to the author’s underexplored potential.

The titular “conjure-man” is N’Gana Frimbo (referred colloquially as Frimbo), an African immigrant and Harvard-educated psychic who practices fortune-telling and related mystical arts in Harlem. One night, his slumped-over frame is discovered in his parlor by two fast-talking locals, Bubber Brown and Jinx Jenkins, who then call on neighboring physician Dr. John Archer to assist them. With a swift examination, Dr. Archer determines that the conjure-man is dead. The discovery of a rather shallow head wound—and later, a handkerchief stuffed conspicuously down the unlucky Frimbo’s throat—unlocks a chilling murder mystery that quickly devolves into a house full of suspects and an ever-evolving timeline of events. Detective Perry Dart and his force are called to the scene to investigate; with the help of Dr. Archer, the deceased’s home transforms into a bustling crime scene where most of the story unfolds.

A truly engrossing murder mystery has a way of creatively shirking formula, and with its unprecedented twists, this tale is no exception. Halfway through, the story’s biggest puzzle is no longer the identity of the killer, but rather whether Frimbo is even really dead: As soon as Detective Dart and Dr. Archer ostensibly narrow down the pool of suspects to a singular assailant, the body of the victim they’re investigating goes missing. When Frimbo reappears, he is very much alive, lucid, and invested in identifying the person who tried to have him killed. After becoming engrossed with the science surrounding Frimbo’s purported death, the reader is then left to this universe’s sense of reality. Is the magic that Frimbo hawks real? Did he really manage to evade death, or is there something else amiss?

Although Dart may be the detective on duty in this winding tale, Dr. Archer is positioned as the primary source of insight and a conduit for Fisher’s own extensive medical knowledge. In some ways, the dynamic between Archer and Dart can feel slightly off-balance, with Dart often deferring to Archer for explanations of key clues without being granted much of a chance to flex his contribution to the case. Still, Archer is shrouded in bookish cleverness, while Dart benefits from his innate knowledge of Harlem, making them a formidable problem-solving duo. We can imagine that the character of Dr. Archer is the author writing what he knows: As a physician himself, Fisher anchored the novel’s finer details in his area of study rather than attempt to enter the psyche of a detective. It allows the reader an opportunity to spend more time with an archetype that so often breezes in and out of mystery novels in a flurry of medical jargon. Here, the doctor is the crime-fighting star, not the conveniently deployed professional.

The suspects—Bubber, Jinx, religious zealot Aramintha Snead, local drug addict Doty Hicks, numbers racketeer Spider Webb, traveling railroad man Easley Jones, undertaker/landlord Samuel Crouch and his wife, Martha—outfit this mystery with their own potential motives for attempting to murder the fortune teller. Their colorful testimonies work overtime to furnish a story with little action. They also contribute to a portrait of the Harlem Renaissance, the epicenter of Black art, enterprise, and culture. Science, religion, and cultural mythos are as embedded in the world of this story as they were in the era itself, with characters like Dr. Archer, Frimbo, and Snead standing as the mouthpieces for these different perspectives. Snead’s position in particular doubles as the typical cautionary tale of the Harlem Renaissance and Prohibition era: a God-fearing woman straying from the church to seek insight from a man who allegedly practices dark magic. Just as her detour from religion leads her to become a suspect in a murder case, religious zealots opposed to the permeating artistic culture often preached of its dangers.

So it shouldn’t be much of a surprise when some of these perspectives come across as antiquated. Bubber and Jinx—recurring characters from Fisher’s first novel, The Walls Of Jericho—serve as a double shot of comedic relief as well as potential suspects. Together they are an example of Harlem’s sense of community dressed as a close, rather comfortable friendship where loyalty and playful jabs are doled out in equal measure. Those jabs are also rooted in a normalized sense of colorism, where dark skin is lampooned in the name of friendly fire. (“Trouble with you… is, you’ ignorant. You’ dumb. The inside o’ yo’ head is all black.” “Like the outside o’ yourn.”) Even a passing investigation of Frimbo’s living quarters results in gendered assumptions cloaked as facts, such as the absence of decoration indicating that he is not living with a woman and, therefore, a “woman-hater.” These moments are plagued by groan-eliciting oversimplifications, sure. But they’re also honest snapshots of dated ideologies, unfortunate blips within an overall compelling storytelling.

For its numerous unexpected turns, The Conjure-Man Dies does fall prey to a predictable ending and a final reveal that a seasoned sleuth can spot a mile (or a few chapters, at least) away. But Fisher’s ability to craft a decent twist and a host of intriguing characters like Archer and Frimbo sparks curiosity as to what he could have been if he had lived longer to nurture his talent. While he’s cemented his place in literary history, there will also be a spot among the greats of the genre, occupied largely by his unfulfilled potential.

7 Comments

Sounds pretty good. I’m sure the twists are not on the level of Harry Stephen Keeler lunacy which is probably a good thing.

I’m looking forward to this one. And I thought Chester Himes did a wonderful job of painting vivid mental pictures for the reader, in A Rage in Harlem.

All the Grave Digger/Coffin Ed novels are great, not just Rage.

Came here to say that. Himes was wonderful. I’m in the middle of a reread of the Greavedigger Jones/Coffin Ed Johnson books right now.I’m really looking forward to The Conjure Man Dies, but I’m going to read Fisher’s Walls of Jericho first. I’ve heard of but not read Fisher before. Kind of embarrassing, but… better late than never?

Eh, according to my Calibre Conjure Man has been in my queue since 08/15/18, so I wouldn’t feel too bad.

Rage is the only one I’ve read so far. The others are on my list, more to look forward to.

Isn’t there a Walter Mosley novel that involves Harlem, voodoo, and a medical doctor? I wonder if it’s an intentional homage. Certainly hard not to hear echoes of “Easy” in “Easley.”