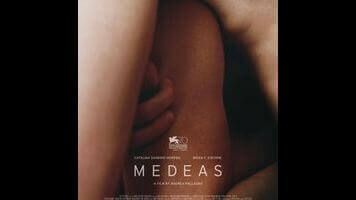

In Greek mythology, Medea is a sorceress of the black arts who helps the man she loves, Jason Of The Argonauts, secure fame and power. The pair weds, but Jason eventually rewards Medea’s devotion by leaving her for another woman. Medea, in retaliation, slits the throats of their children. In nodding to this portentous figure in the title, director Andrea Pallaoro hints at the dark direction her debut feature might take. But the newcomer also gives the myth a gendered twist. With limited dialogue and long takes, Medeas quietly builds to inevitable tragedy, exploring the darkest corners of desire, jealously, and unforgivable transgressions.

Set in an undefined time and place (analog era, based on the Walkmans and black-and-white TV, and rural, based on the hills and cows), Medeas opens with a foreboding shot of a man floating face down in a pond. Two children tread water on either side of the Ophelia-like figure, wary to approach but curiously compelled to draw nearer. With a splash and screams, the man suddenly leaps to life, capturing the children in an embrace. This is Ennis (Brían F. O’Byrne), a religiously stern father of five children and husband to the enigmatically silent and much younger Christina (Maria Full Of Grace’s Catalina Sandino Moreno). Despite this initial portrait of domestic bliss, Ennis’ harsh ways quickly become apparent. Meanwhile, Christina, though looking the part of the apron-donning and baby-toting devoted housewife, begins retreating further and further from her spouse.

Pallaoro brings a keen visual eye to this domestic-drama-turned-nightmare, relying on beautifully shot observational vignettes rather than exposition to paint a picture of the pastoral family’s implosion: the teen daughter applying makeup and leaving a defiant red imprint of her lips on a mirror; the middle sons playing in the dust of a gas station as Christina disappears into the owner’s rundown trailer for playtime of her own; the infant child left alone in his cradle, cooing at the world above him. The characters all rarely appear in the same frame together, which is the filmmaker’s way of evoking the nuclear family’s rapid collapse into irrevocably broken parts. And the magic-hour cinematography eerily contrasts with the pervasive sense of doom.

Alas, the intentional ambiguity does wear thin, especially in the movie’s final act. By the time Ennis finally takes action, Medeas gives way to an identifiable pattern and rote clichés (a bird trapped indoors; a tearful walk in the rain). Most disappointingly, the film culminates in a frustratingly anticlimatic cut to black, which feels like an apathetic narrative shrug in lieu of a poignant final punch. But these flaws speak more to the potential in Pallaoro and co-writer Orlando Tirado, as the story they’ve spun from the ancient myth begs for more discussion, opening up fresh questions that people have been grappling with for millennia.