The director of Room 237 cracks the code of simulation theory with A Glitch In The Matrix

Film Reviews A Glitch In The Matrix

Note: The writer of this review watched A Glitch In The Matrix on a digital screener from home. Before making the decision to see it—or any other film—in a movie theater, please consider the health risks involved. Here’s an interview on the matter with scientific experts.

Rodney Ascher is a scholar of obsession, and sometimes a conduit for crackpots. Each of his documentaries is a peek into overactive imaginations, allowing subjects to hold court on whatever haunts their dreams, literally or otherwise. To enjoy these plunges down the rabbit hole of the racing human mind requires a fascination with fascination. Ascher’s first feature, the absorbing cult-of-Kubrick essay film Room 237, seemed to tick off plenty of folks who mistook its presentation of variably persuasive interpretations of The Shining as some sort of concurrence with each of them. Or maybe the detractors just felt that even airing those wild takes was a waste of time. Certainly, there will be those who feel the same, and probably more strongly still, about Ascher’s new movie, A Glitch In The Matrix, which focuses on a conspiracy theory that’s grown steadily in popularity over the last couple decades: the belief that we’re all living not in a physical world but in a computer simulation of the same.

Early into the film, Ascher cuts to footage from 1977, when Philip K. Dick, the almost premonitory sci-fi guru whose stories inspired Blade Runner and Total Recall, stepped to a podium at a convention to reveal his conviction that reality as we perceive may not be reality at all. That’s a notion much older than Dick’s influential mindbenders, and older than computers, too; as one talking head points out, it goes back to at least Plato. But Dick’s paranoid remarks, which form a kind of rhetorical backbone (Ascher returns to his speech throughout the film), floated much of the fundamentals of what we now call simulation theory—an idea that gained lots of new followers with the release of The Matrix in 1999, the publishing of Nick Bostrom’s seminal essay “Are We Living In A Computer Simulation?” in 2003, and the propagation of it as a legitimate possibility by the likes of Elon Musk and Neil deGrasse Tyson.

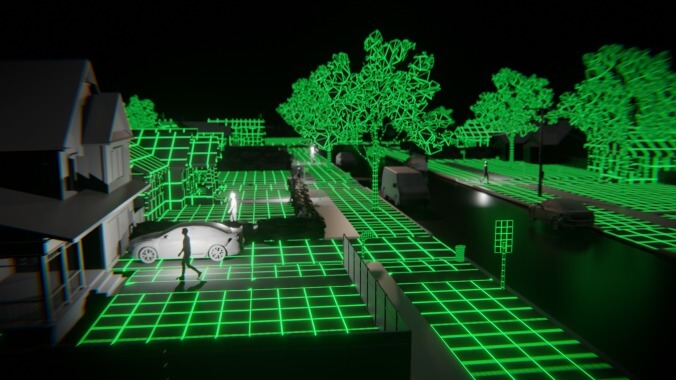

A Glitch In The Matrix unfolds as a flood of exposition and conjecture, accompanied by a gaudy infotainment montage of video-game footage, movie excerpts, and computer-animated recreations. On its chosen subject, the film is not comprehensive: That there’s no mention of, for example, the supposed “glitches” (like Trump’s unlikely victory) that have fueled proponents of the theory of late, nor the news that billionaires have funded scientific campaigns to free us all of our artificial construct, betrays more psychological than journalistic interest. As usual, Ascher assembles a brain trust of true believers to discuss what might charitably be described as their mutual preoccupation, less charitably their shared delusion. These four “eyewitnesses,” as the film labels them, speak from behind elaborate digital avatars, possibly to disguise their identities (one confesses that he’s a teacher, a job one assumes might be jeopardized by the revelation that he holds this particular belief) or perhaps just for visual-conceptual consistency. That each ends up looking a little silly, expounding straight-faced theories in cartoon video-game form, is one of those little details that helps underscore that—in social-media parlance—Ascher’s retweets are not necessarily endorsements.

Ideas are infectious. Ascher conveyed as much in his last documentary, The Nightmare, which explored the phenomenon of sleep paralysis as a prime example of the war our brains wage against us. (At the film’s Sundance midnight premiere a few years ago, you could feel the whole auditorium shift uncomfortably in their seats when one interviewee disclosed that the frightening condition could be “contracted” through suggestion—that people have actually experienced sleep paralysis after learning about it!) For as slyly amusing as A Glitch In The Matrix can be as a portrait of collective hair-brained hypothesizing, the film acknowledges the potential danger of buying into such a philosophy. If nothing’s real, what’s to ethically stop you from mowing down your neighbors? To that end, the film’s most disquieting sequence throws audio of convicted murderer Joshua Cooke, who pleaded the so-called Matrix Defense in court, recounting the killing of his parents over a kind of first-person shooter tour of his house, digitally recreated. It seems intended as a cautionary tale, but offering Cooke this platform at all isn’t in the best of taste.

If none of this is as gripping as Ascher’s past investigations into the labyrinth of the mind, it’s largely because the filmmaker is this time doing more summarizing than probing. Room 237 and The Nightmare opened portals into the personal headspace of their subjects, into their torments and interpretative gymnastics, the horror movies created by or imprinted upon their brains. The ideas tossed around in Glitch have been widely disseminated: A quick Google search reveals dozens of articles, all with essentially the same headline, that go into this outlandish postulation in greater detail. Exhaustive or not, the film sometimes plays like little more than a fast-paced primer on the basics of simulation theory. Even when Ascher hits The Matrix itself, the readings are all textual and surface level; one misses the way he turned The Overlook inside out, using the big reaches of his armchair analysts as a blueprint.

Simulation theory sounds like a nightmare, but it’s more of a daydream—a fantasy that every moment in life that seems unfair or inscrutable is just a flaw in the algorithm, not proof that the universe abides by no algorithm. That’s the USB chord that connects A Glitch In The Matrix to Ascher’s past work: Just as Room 237 was less about The Shining than the meaning we seek in every crevice of the pop-culture we love, this film uses simulation theory as a window into the desperately human search for order and logic, with technology as just another variant on some grand designer outside the membrane of our consciousness. Here and there, Ascher’s committee of talking heads reveals a flicker of self-awareness, and you wonder if this is what the filmmaker was after all along. One of them, for example, briefly muses about how it makes sense that he struggles to connect with other people, given that the world everyone occupies is just a big, phony cluster of code. Is it any wonder that he doesn’t follow that cursor of thought to a scarier, more logical conclusion?

54 Comments

Fun Fact: It’s not a computer simulation, but a board game.

Many people who believe in the simulation hypothesis (not that I’m one) think it could be a cellular automaton such as the Game of Life (no, not the one with the cars and little pegs for spouses and children, but John Conway’s “Game of Life”). Apparently before people wrote computer versions of Life, Conway used a chessboard to work it out. So it could be a board game.

I actually believe it’s Tim Conway’s “Game of Dorf”…

I think Conway’s first effort was with graph paper, but moving pieces around a chessboard was better than pencilling in/erasing graph paper squares.

My life? More like a bored game.

Hey-oooo! 👏

….and everybody gets a little plastic car with pegs for people!

You stupid child.

It’s like Mousetrap mixed with Battleship.

Mine is more like Sorry, with a little bit of Trouble.

As long as it isn’t Hungry, Hungry Hippos.

So you’re saying that I’ll never sell my deed to Baltic Ave?Well shit.

So true – we’re all just wooden meeples who want bricks but only have sheep 🙁

allamaraine, count to four

Specifically, its Space Hulk 3rd Edition. The 2011 reprint, not the 2009 first printing.

Room 237 seemed to be based on the presumption that any opinion, no matter how out there and uncredible, deserved to be heard. Obviously that movie is not responsible in any way for what we’re seeing play out now but I can’t think of a thesis that has aged worse than that one. No, your insanity does not automatically deserve a platform.

I wonder if there’s a larger dynamic here where the democratization of information has largely neutered our traditional gatekeepers to the point where those same gatekeepers feel obliged to give almost everyone a hearing. A few years back my local newspaper — in an extremely liberal college town — published a letter to the editor where the writer just blithely accused local election officials of making up votes at the end of election night to pass some ballot measure. And I remember being utterly stunned that the paper would just run that letter — you’re not the town’s Facebook page! You don’t have to publish every damn e-mail you get!Fortunately, things have gotten much better since then and instances of wild, evidence-free allegations about election fraud have completely disappeared and not at all advanced to the national level with terrifying and tragic results.

That’s why I never take an information as granted anymore.I always double check it on wikipedia.

Democratizing technology may have its flaws, but was there ever a time when we were led by a group of wise, benevolent information gatekeepers who didn’t abuse their power to withhold information from us?

The CNN morning show yesterday was interviewing the guy who was retiring from the head of their fact checking division. When he was asked about what he thinks CNN should be doing more of, he stated that he thinks they should be giving more time to opposing opinions(in context, meaning that they should have more conservatives on the air).

And that’s the guy who ran their fact checking division.

Late reply I know, but it always bothers me when I see this sentiment, given “traditional gatekeepers” include the likes of Fox News and the Daily Mail.It’s a double-edged sword to be sure, but it’s not like venerable institutions have proven any more trustworthy – just more consistent.

Ehh, when the uncredible opinion is about a movie I don’t see any issue. We all speculate and try to draw connections to things without any real facts when it comes to fictional mediums. It’s fun. When the uncredible opinion is on climate change or vaccines, then we have a problem.

Bbbbbbut the first amendment says I can! Waahhhhhhh!

Also, it was just kind of dull. The documentary itself had no voice of its own and, while there’s something to be said for letting the theorists speak for themselves, it just results in a bland montage of voice overs. I read the feature about the film and the theories in it in Empire Magazine before seeing it and was then disappointed that the film itself added nothing to the information on the two page spread. No investigations into them, no context, no voice at all. It was a feature length YouTube video. Sounds like this is more of the same.

Completely agree – it was repetitive and boring

HBO’s recent DB Cooper doc has a similar structure but I felt that was a lot more interesting, given the events these people described actually happened to them (or at least they really believe it happened, and none seemed outright delusional.)But yeah, I think there’s a danger at times in pretending that anyone and everyone deserves to be taken seriously, which some of these theories in 237 and presumably this one as well probably shouldn’t be. I’d argue though that at least a film like this is less harmful than the many other outlets the really harmful crazy folks have now.

I don’t understand how you could infer that Room 237 is based on that presumption? Surely the best you can infer is that “this group of people with unusual perspectives on this particular film deserve to be heard if an interesting film can be made about it”. That’s a pretty bold inference to draw.

I came down to write something similar. I don’t think the movie was reprehensible or anything, but I was baffled about the praise it got.

I mean, Erroll Morris has been showcasing people with odd outlooks since Vernon TX, through Gates of Heaven and Fast, Cheap, and Out of Control. Among other filmmakers who showcase niche groups and outlooks. I’m not sure why this one’s burrowed so deep under your skin.

Erroll Morris does so with a critical eye. He doesn’t take what they say at face value. Room 237 was just a series of crackpots going on about stuff, but there was little to no context to it. Their views were presented as if they were legitimate.

I’m not sure I’d agree. I went into Room 237 pretty blind, and pretty early on you realize 1) these people don’t all have the same things to say about the movie, so obviously the underlying thrust is “look how one movie can invite such wild interpretations” 2) most, if not all, of these theories barely hold up to scrutiny, obviously these people are projecting their own ideas onto the movie (most obviously with the guy making “Kubrick shot the moon landing” connections, more subtly-yet-desperately with the guy assuming the hotel’s illogical layout is intentional and not simple continuity error).

You’ve put your finger on the key point. The different theories are all such complete worlds that they are incompatible with one another and thus the format of combining them into a film explicitly points to their fiction.

Stegrelo’s kinja account seems to be based on the presumption that any opinion, no matter how out there and uncredible, deserved to be read. Probably, that comment is not responsible in any way for what we’re seeing play out now but I can’t think of a thesis that has aged worse than that one. No, your inanity does not automatically deserve a platform.

I think it’s quite possible to analyze false opinions, learn about them, and present them to others without advocating for them.

Following your logic here, we shouldn’t have scholarly studies of the Holocaust, because that means Nazis “deserve to be heard.”

There have been variations on this theme throughout history but it was usually posited as a thought experiment, not something to be taken literally. The flat earth trope was sort of a running joke for years in the same manner. Suddenly people started taking it as a real thing.

I feel like Scientology had to be started as goof, but evolved. Or it was a weird drug fueled hypothetical discussion “That makes so much sense man!!”. Perhaps a combo.

Same thing happening with Qanon. Basically started as a joke or troll experiment (and I think even some of the people who are rabid Qanon fanatics aren’t completely sure if its factual or not, but it makes them feel powerful so doens’t matter)

And I was like you brought the bread, and he said nope, and i was like, dude!, but suddenly there was bread everywhere, and i was like, woah, where did it come from, and he was lol.

I’m pretty sure it started as a way for Hubbard to make boatloads of cash and not pay taxes on any of it. He did start drinking his own Kool-Aid at some point though; in Going Clear a former Scientologist relates a story about how Hubbard was convinced he had a “body Thetan” so strong that he wanted this guy, who was an electrical engineer, to build like an e-meter on steroids that would shock it out of his body, even if it killed him in the process.

Harlan Ellison tells the (possibly apocryphal) story of a time he was drinking with a group of other writers, I think including Theodore Sturgeon, Fritz Leiber among other heavy-hitters. El Ron Hubbard was also present.As drunk writers were wont to do, they bemoaned their general lack of the filthy lucre. I think it was El Ron himself who observed that if a fellow wanted to acquire some serious scratch, starting a religion would be a splendid way to go about it.El Ron also lived on a houseboat with many young men for *ahem* tax purposes. And he was a shitty writer to boot.

people who learn philosophy from reddit threads aren’t taught that most philosophical questions aren’t meant to be taken as actual, literal arguments

That’s exactly what a Platonist would say!

That’s exactly what a Platonist would say!

Okay; life-long computer engineer here folks, and let me spell it out nice and easy: You know that game, Sim Earth? Well the way it’s done is, a bunch of math happens to a bunch of numbers, then it gets turned into dots on a screen and you are amused. You know how it ISN’T done? A little tiny crude version of a planet inside your computer box, with little tiny weather and buildings and people. THERE IS NO “LIVING IN” A SIMULATION, because there is no “IN” part. It’s just a bunch of math happening to create a visual effect on a screen.

Okay, so, how about if we back off of that and say, “my brain is real, but everything ELSE is a simulation!” Well, hey, that’s just Plato’s Cave. No need for me here. Good luck with that. (Hint: Try Occam’s Razor)

“Are We Living In A Computer Simulation?” No. Thank you for coming to my TED talk.

It always makes me wonder is there are any “conspiracy theories” that have a basis in reality.I mean: come on. Really?Reagan/Bush ran guns for drugs? Come on.The Central Intelligence Agency was dosing U.S. citizens with LSD without their knowledge? Come on.The U.S. government gathered data on its citizenry via a massive intake through cell phones and emails? Come on.Men of color were deliberately infected with syphilis and allowed the disease to run rampant? Come on.This, and every other mindset like it, should be approached IMHO like a comparative religion study. No, you don’t have to believe it but you learn much if you listen with respect. Hell, you may even discover a truth in there, somewhere… even if the truth sounds a little strange.Oh. And because people have forgotten how to actually read for content… /s

I don’t think the Tuskegee experiment involved deliberate infection with syphilis… BUT, it did involve preventing subjects from getting treatment in order to see how the disease progressed.

Point made. I was incorrect in the deliberate infection. Leaving it wrong to make sure your point is properly in context.

Peas.

Is there a trend of “documentaries” (like “The Nightmare”) with zero research, zero analysis, and just a random collection of subjective opinions placed on equal footing ?Because it sounds a tad lazy to me.

The problem I have with Ascher’s work is that it’s just too boring.Room 237 seemed to go absolutely nowhere, I watched The Nightmare hoping to learn something about REM paralysis, (something I’m a chronic suffer of, not a week goes by without it happening), but again, it just meandered away into nothing.

I’m an agnostic and I don’t have much use for religion myself, but I don’t begrudge people the need for belief that there is some greater design to everything, especially in trying times. When I see big conceptual theories like this, it looks to me like people trying to create their own custom-made religion. They can cloak it in as much techno-jargon, but it still seems to be belief in something they have no direct evidence of. And, like mundane religions, I don’t really have a problem with that, in so far as they aren’t using it to justify shitty behavior.

It has never been soothing to me to think it’s all a plan (whether it be God or some other entity.) Quite the opposite, actually. If God’s plan includes as much horror and pain and trauma and fear that we have in the world, that’s a vicious god and I want no part of him. For a while I was OK with the idea that God started the world and then just kind of forgot about it (like a person might with a science experiment or something.) But even that seems like an entity not worth my worship.The idea that everything is just random seems to fit a lot better and it’s a lot more comforting. I don’t know how “it’s all God’s plan” can be comforting to anyone.

My brother has halfway believed we’re in the Matrix since Anthony Weiner’s career imploded. “A guy named Weiner can’t stop sending dick pics? C’mon.”