The Terminal at 20: Steven Spielberg’s American limbo

Caught between big emotions and a big suspension of disbelief, this fairy tale about a man stuck at the airport resonates for those trapped in the in-between

Film Features Steven Spielberg

Out there in the world of extremely-online cinephilia, there is an abstract idea called Top Shelf [insert name of a beloved auteur]. Even though no one can agree on, say, the best Pedro Almodóvar movie (it’s All About My Mother), or Paul Thomas Anderson’s greatest achievement (let’s say Phantom Thread), few would disagree that these examples belong in their respective filmmaker’s highest ranks.

But when it comes to Steven Spielberg—one of the greatest living American filmmakers—boy, does the definition of “top shelf” vary wildly. Take his 2004 delight The Terminal, for instance. I doubt anyone would place this lovely drama-comedy, about a heart-tugging case of incidental displacement and isolation, on the same tier where films like E.T., Jaws, Schindler’s List, or The Fabelmans proudly sit. (See, I know some are already shaking their fists at me for that last title. It’s a masterpiece, get over it.) But over the years, this critic heartily decided to place The Terminal (which opened to mixed critical reception in 2004) on Spielberg’s stuffed and arbitrary top shelf. Every once in a while, a film and the messiness of your own life sync up on such an inexplicable level that it instantly becomes a part of your personal history. That’s what happened to me in 2004, a tricky year in my admittedly privileged life.

I was 26, a New Yorker of four years after moving from Turkey to receive my graduate degree at the City University of New York. Graduate school days were already behind me at that point and I was working as a low-level account coordinator at an advertising agency—a grueling job with comical pay and long hours, but one that was nonetheless educational and accepted my temporary work visa. I hated the work, but I excelled at it and I was happy in lots of ways. I was in love with another lowly account assistant (now my dear husband of 17 years and counting), I could miraculously afford a decent-enough rent-controlled apartment on my own, and I was making it work somehow. But whatever I thought I was achieving came to an abrupt halt when I got slammed by the brutal reality of my fast-expiring visa. My legal case to convert my temporary work permit to an H1B (which is a more stable kind of work visa that your employer must sponsor) got rejected by the government—in short, they thought I had no business stealing a job from a documented American. I could re-appeal or pack up and leave the country permanently.

Both then and looking back now, I have been acutely aware of how privileged a position I was in despite the circumstances. My family was supportive of my immigration plan, I could afford a graduate degree from a public university, and my employer agreed to pay for most of my legal expenses. Plus if things truly didn’t work out here, I had a welcoming home and good opportunities back in Turkey. So in no way do I know what it feels like to be an undocumented immigrant with limited (or no) options in this country. But I can speak to my personal experience, and the headspace I found myself in back then. It was suffocating. I was working hard and dreaming big, and the thought of giving all of that up made me miserable. So I re-appealed.

What followed was a limbo that lasted…well, I don’t know, but months that felt like years. I put every dream on hold. In every conversation, I had to consider my possible expiration date, mentioning no future plans whether they would be taking place in one week or one month. In other words (whether I knew it at the time or not), I felt like a part of me was living at the airport—to finally arrive in earnest or to leave for good—waiting for the inevitable.

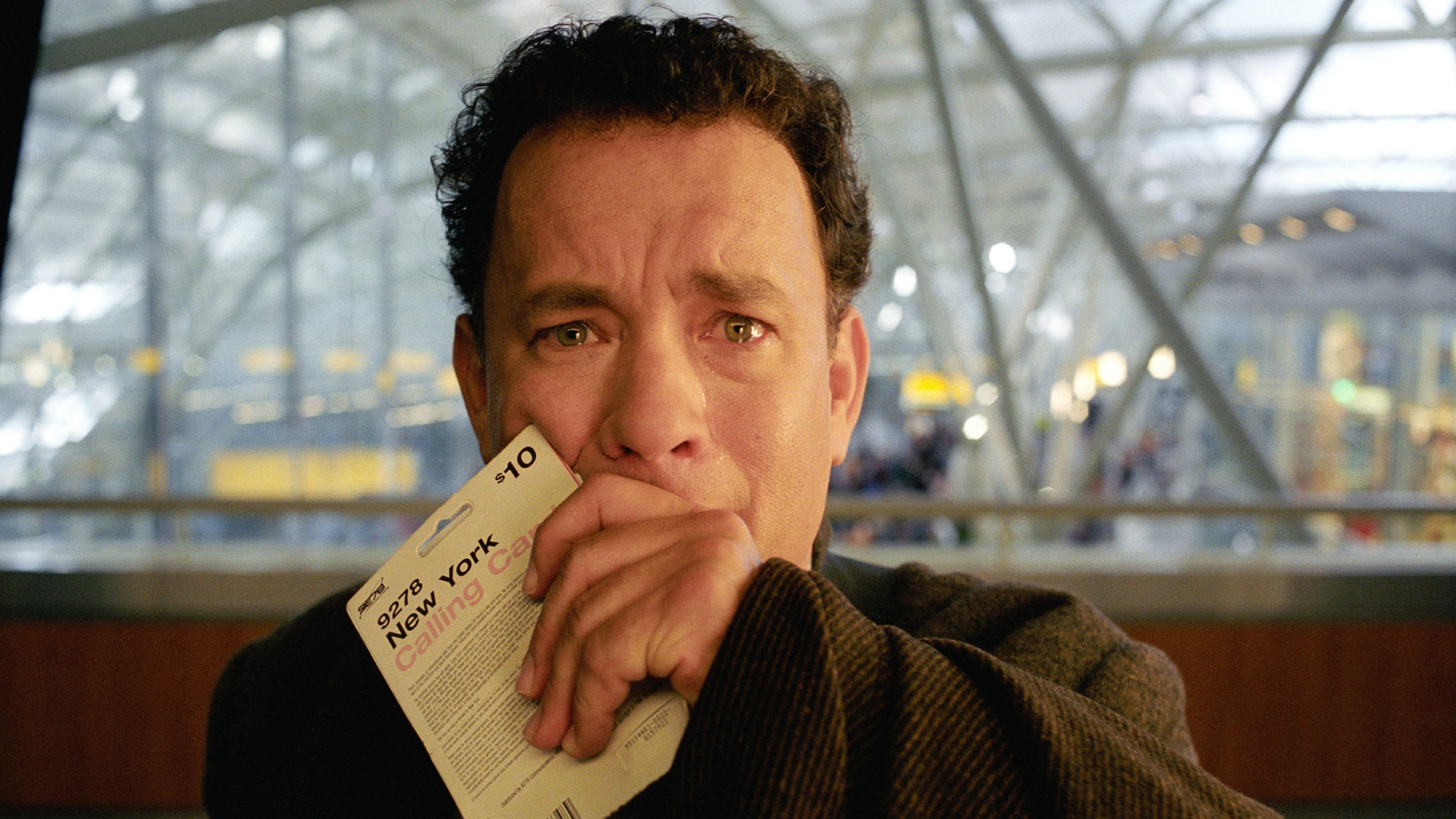

This is when I met Spielberg’s contemporary fairy tale The Terminal, about the pure-hearted Viktor Navorski (Tom Hanks), hailing from the fictional (but plausibly-named) Eastern European country of Krakozhia.

Written by Sacha Gervasi and Jeff Nathanson (and very loosely based on the real-case of Mehran Karimi Nasseri, who lived at Charles de Gaulle Airport from 1988-2006), the fable goes like this: Navorski arrives at JFK Airport in New York as a coup d’état sends his motherland into chaos, invalidating his passport and leaving him without an official homeland recognized by the U.S. Sporting a cutesy (but amiable) accent and broken English, and trying to make someone, anyone, care about his heart-wrenching dilemma, Navorski watches the war back home in horror on various airport screens, while holding onto a mysterious peanut can (whose contents we find out about later) for dear life. The story’s cruel villain arrives in the form of Stanley Tucci’s Dixon, an exceedingly unsympathetic Homeland Security paper-pusher who’s quick to drop a racist remark about Asian tourists and who’d do anything to get the promotion he feels he’s overdue for. Out of options and unable to let Navorski stroll into the country, Dixon just lets him stay in the international transit lounge until things settle in Krakozhia, or at least until he figures out how to make Viktor someone else’s problem. Little does he know that that would take nearly a year.

The Terminal requires a suspension of disbelief that today’s exceedingly cynical audiences might not have the stomach for. For starters, where is this version of JFK that has a decent view out of Dixon’s office? More importantly, why is this the only terminal of JFK that doesn’t look like a cursed hellhole? (That part might have something to do with frequent Spielberg collaborator Janusz Kamiński’s gorgeous storybook cinematography and signature lens flares.) Why is Viktor the only Krakozhian passenger around? How is this terminal logistically laid out in relation to the rest of the airport, including passport control and immigration booths? Was there ever a system in NYC where you’d return a luggage cart and get a quarter back, which, for a while, is Viktor’s only money-making method for buying burgers and sodas? (There wasn’t.)

But that’s the Spielberg miracle. The Terminal is so big-hearted and so set on wearing that giant blubbering heart on its sleeve that none of these ludicrous holes seem to matter. In fact, my shrugging off all of these questions mirrors the way in which A.O. Scott seemed to have shrugged off the film’s loud emotions. “Rarely have I been so acutely aware of a movie’s softness and sentimentality, and rarely have I minded less,” Scott wrote in his New York Times review. As the kids would say these days, “It me.” I was so on the movie’s wavelength that when a random passenger asks Viktor, “Do you ever feel like you’re just living in an airport?” I almost raised my hand in the theater.

Throughout The Terminal, I remember sobbing (and I mean sobbing) as those around me mostly giggled in amusement as Viktor tried to build a temporary life for himself in limbo—which is what I felt I was doing in many ways, feeling rootless and isolated. Through immersive montages and tracking shots (I can’t emphasize this enough—Kaminski’s movements make this airport beautiful), Spielberg follows Viktor as he claims an abandoned gate as his home base, uses the terminal’s restrooms to freshen up in hilarious ways and collects as many quarters as he can before Dixon puts an end to it. And through it all, the film’s heart is disarmingly simple: Viktor is alone but resilient, and he will make the absolute best of a crappy situation, damn it. Perhaps that was what touched me most deeply, witnessing Viktor’s stubborn dignity in a country that doesn’t want him, when that same country had just told me, “We don’t want you.”

Still, Viktor’s loneliness doesn’t last long. Alongside John Williams’ playfully chromatic score with a vague (but deliciously catchy) Eastern European musicality, Viktor finds himself warmly coddled by a diverse clan of airport workers. Among them are Chi McBride’s luggage supervisor Joe, Kumar Pallana’s cheeky janitor Gupta, and Diego Luna’s charming Enrique, a well-intentioned employee in charge of several flights’ first-class meals, head-over-heels for Zoë Saldaña’s immigration officer Dolores. Soon, Enrique and Viktor make a deal: Viktor will learn as much as he can about Dolores during her routine rejections of Viktor’s entry attempts and, in exchange for that information, Enrique would feed Viktor indefinitely. There is also Catherine Zeta-Jones’ dreamy flight attendant Amelia, jerked around by a rich married guy for so long that Viktor’s genuine romantic gestures and honesty touches her, like it touches the rest of us. And in time, more join this blue-collar coterie—namely, a group of construction workers so impressed with Viktor’s renovation skills (yes, he does frequent and totally implausible renovation jobs around the terminal, for fun), that they hire him on the spot for an opening, paying him a good salary under the table.

From E.T. to Bridge Of Spies, from Jaws to Jurassic Park, many a Spielberg film references the clueless (and sometimes evil) power structures which threaten the lives of everyday heroes. In the most enchanting way imaginable, The Terminal overdoses on this theme, leaning closely into a microcosmic idea (or ideal) of the post-9/11 New York City, where the citizens who were on the right side of history had—or were supposed to have—each other’s back, uniting around the unjustly otherized.

This moral idealism obliquely culminates in a scene where a disheveled, helpless Russian man with a sick father back home desperately tries to leave the country with the much-needed medicine he has hoarded for his dad. Dixon stands in the way but, serving as a translator, Viktor saves the day, earning the approving looks and admiration of an entire airport staff. A good man with proud morals until then, Viktor reaches legendary heights in this moment—one that might be too saccharine for some, but was inspiring for me (and my tear ducts) at the time. I was often bad-tempered, impatient, and self-pitying in those days, thinking nothing was going my way. Perhaps I needed a role model like Viktor, someone to remind me that the most any one of us could sometimes hope for is to do our best, be our best. And if there is an actor out there who can sell this hopelessly romantic idea of wholesomeness better than Tom Hanks, then I admit, I don’t know him. Hanks works many of his comedic and dramatic muscles here, tangentially bringing to mind his loose-limbed Splash appeal, Apollo 13 dignity, Forrest Gump purity and Sleepless In Seattle romantic magnetism and paternal gravity, all in one package.

Meanwhile, I do wish The Terminal’s handle on a low-paid immigrant’s reality was a little less coy—its naïve disposition especially leaves you wanting more substance from Gupta, a character whose troubles feel sugarcoated in the aftermath. In an operatically melodramatic sequence when Gupta gives it all up (his job, maybe even his safety) to help Viktor in the most dignified way imaginable, the sentiment we feel is consistent with the film’s overarching folkloric demeanor. Still, something in the scene’s aftertaste doesn’t sit right—previously, The Terminal clearly establishes that Gupta was in the U.S. out of necessity. But by implying that it is in his hands to make a different choice, the film comes uncomfortably close to the privileged assumption that such life decisions can be purely made by the individuals in question, regardless of one’s documentation status.

Nevertheless, it’s partly thanks to a familial collection of such selfless people that Viktor finally succeeds in entering the United States of America (I cried again), managing to keep a promise he once made to his own dying father. (There is often a reflective parental angle in Spielberg’s stories, and the one in The Terminal is simply exquisite, a powerful detail I don’t wish to spoil here just in case.) Meanwhile, it’s no spoiler to say that I finally had my visa approved on the long road to my eventual U.S. citizenship, which I got over a decade ago. Revisiting The Terminal recently, I was happy to see that Spielberg’s sweet make-believe tale hasn’t lost its appeal or beauty for me as someone who still feels a sense of limbo in her Turkish and American identities.

The Terminal promises you a fairy tale and delivers a bountiful one. Spielberg made it for everyone who feels the pull of home, one that might not always be under a tangible roof. Sometimes, it’s within the warm embrace of a compassionate community that can make even the most soulless of spaces seem cozy.