Not all great horror stories are “about” something, in the sense that their monster (or monster equivalent) functions as a metaphor for a non-supernatural fear. But this is a quality a lot of consensus masterpieces share. The horror genre is uniquely suited to commentary and social criticism, and the stories lacking such subtext have to get by on craft alone. If a horror writer or director does both—a story that’s not only told well, but which taps into a deeper anxiety—it’s satisfying in a balanced-meal sort of way, while just having a good idea (but executing it badly) or just having good craft (in service of a shallow story) can mean a struggle to transcend junk-food territory.

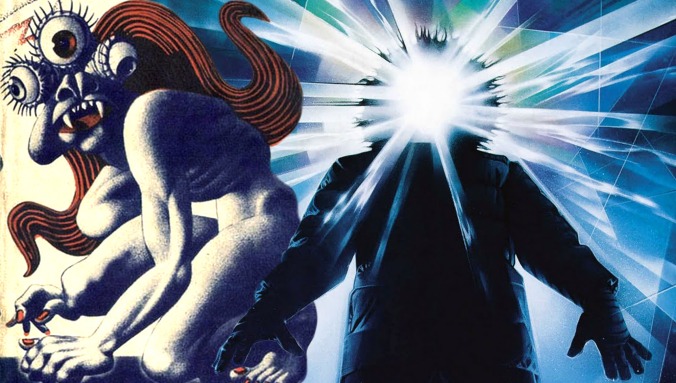

Craft for its own sake is really the best way to describe all three versions of Who Goes There?, the highly influential story about a shape-shifting alien found in the ice of Antarctica who stalks the members of a scientific expedition. John W. Campbell’s original novella is a pure monster story and so are its two primary film versions: 1951’s The Thing From Another World, directed by Christian Nyby, and John Carpenter’s The Thing, released in 1982. However, each are a pretty representative example of sci-fi storytelling craftsmanship from their respective eras: the pulpiness of genre writing when it was still a niche interest (the novella was first published in Astounding Science Fiction in 1938), the effective-but-corny efficiency of the Golden Age studio era, and the enjoyable excess of 1980’s blockbusters. The question of which version is best comes down to which of the three styles is most to your taste, as the story itself doesn’t give you a lot to hold onto.

This is probably why Campbell’s novella, while considered a landmark of the genre, doesn’t show up on more general syllabi the way Shelley or Stoker do. Frankenstein isn’t just about a reanimated corpse, but about hubris, and the danger of humans playing God. Dracula’s not just about a vampire, but about the very human desire to give into dangerous, sinful urges.

Who Goes There? could be read as a parable about trust, but that feels like a stretch. Really, it’s just about a shape-shifting alien, but give Campbell credit: that’s an awesome idea. His novella is the modern birthplace of what can be dubbed the “are you infected?” genre, from which you can draw an easy line to a lot of modern vampire and zombie stories—basically anything where people are secretly “turned” but still look the same. (Other descendants: Michael Crichton’s Sphere is an explicit rip-off of the general premise and story.) The idea that your friend isn’t actually your friend is incredibly potent, although Campbell doesn’t exploit this for deeper resonance, and neither do Nyby nor Carpenter. Some 18 years after Who Goes There? was published, Invasion Of The Body Snatchers would deploy a similar idea to vastly more sophisticated ends, synthesizing its pod-people paranoia so well that people continue to debate whether it is more accurately read as being about Communism or a warning against anti-Communist hysteria.

Campbell had no such underlying agenda; he simply wanted to spin a good yarn, just as Nyby did, and just as Carpenter did, although Carpenter had the additional goal of showcasing the latest in Hollywood makeup, effects, and gore. (Coincidentally, The Thing was released the same day as Blade Runner, another film where the hero is tasked with determining who is and isn’t human. That The Thing’s test involves blood while Blade Runner’s concerns memory shows how that film more deeply probes the idea suggested by Campbell.)

Each adaptation has a major change from the book, but it’s curious how neither feels like they matter too much since there’s no underlying theme violated or misinterpreted by the change. Certainly the core is recognizable in all three: the icy setting (North Pole in the first movie, Antarctica otherwise), the stalking predator, no-nonsense men doing a job together. The Thing has Kurt Russell’s icy cool presence leading his crew, while the team in From Another World fits neatly into the Howard Hawks tradition of professionalism (Hawks produced the film, and is rumored to have directed much of it). Dialogue in the book, meanwhile, is so hard-boiled it shatters: If the creature gets loose, the leader muses, “it is his avowed intention to kill each and all of us as quickly as possible, which is something we don’t agree with.”

In other words this isn’t a case like The Shining, where the book is saying one thing and the film says something else.

Who Goes There? kicks off en media res, with the scientists who discovered the ETcicle having brought the supposed corpse back to their base and debating whether to risk an autopsy. From Another World rewinds a little, so that we see the team find and then trace the outline of the crashed craft. There’s a great moment when the camera cuts to an angle that allows us to see the dimensions of the mysterious ruin, and we realize it’s a flying saucer—the film’s best example of where it’s old-school craft shows its effectiveness.

In The Thing, the crew doesn’t discover the craft or the creature. Carpenter’s film opens (after a brief prologue where the ship crashes to Earth) with a dog charging into the camp, followed by a helicopter where a shooter is trying to gun it down. We’ll eventually learn the dog was the alien, having shapeshifted into canine form, while the man, gunned down by a member of the American team, desperately tried to stop it. (2011’s The Thing tells the story of this crew, letting it claim to be a prequel while serving as a remake to Carpenter in every important way.)

The way the crew encounters the thing is the biggest change of Carpenter’s version, and you can see how it doesn’t really make a difference to the story, structurally or thematically. The Thing simply showing up in camp doesn’t say anything about the human characters, just as it doesn’t say much when they go and discover it. This isn’t like Frankenstein, where how the monster comes about is a cautionary tale; starting this way allows Carpenter to kick things off with action, just as the book’s start lets Campbell cut right to the quick. From Another World is the only one of the three that follows a traditional arc of the conflict being introduced gradually and then intensifying, which under the circumstances feels like an old-school throwback.

From Another World’s change is more fundamental. Rather than the famous shape-shifter, the film turns the creature into a Frankenstein’s monster type, a lumbering force of brute strength that feeds on blood but doesn’t change its appearance. (This was the first movie my dad ever saw, and decades later he still recalls that the creature is biologically closer to a carrot than a man.)

Presumably this change was made because 1951’s effects couldn’t handle the required metamorphoses, and because films just didn’t get this graphic back then. That’s one thing Who Goes There?, in all its pulpy glory, can revel in:

Abruptly it rumbled disapproval throatily. Then it laughed gurglingly, and thrust out a blue-white, three-foot tongue. The Thing on the floor shrieked, flailed out blindly with tentacles that writhed and withered in the bubbling wrath of the blowtorch. It crawled and turned on the floor, it shrieked and hobbled madly, but always McReady held the blowtorch on the face, the dead eyes burning and bubbling uselessly.

Carpenter would take all these descriptions as gospel and a challenge, with stomachs that turn into gaping mouths, heads that walk around on spider legs, and a dog whose head splits open. It’s a high watermark of the pre-CGI era, but even if you could’ve accomplished those kinds of effects in 1952, something on the intensity of Campbell’s descriptions wouldn’t have made it through the Hay’s Code.

The new monster means no “are you infected”-type suspense. There’s no scene when each man has his blood tested to confirm he’s still human, a moment that is a highlight of Carpenter’s version. But because “who is human” is more the plot than the point, this change feels less fundamental than you might expect. If a good storyteller is throwing a monster at you, the specifics of the monster itself just amounts to details.

Start with: Campbell’s novella has been justifiably overshadowed by Carpenter’s film (and the original to a lesser extent). His monster is a lasting creation, but the book itself is forgettable. None of the characters are distinct, and it’s oddly tedious for a story that’s nonstop plot and action. No doubt genre fans will better appreciate the place it (and Campbell) holds in the canon, but I wouldn’t recommend it to anyone who wasn’t already a big enough horror fan to have found it on their own. I am personally a big fan of studio-era Hollywood, and as such have the most affection for The Thing From Another World, but Carpenter wins this one in a walk. Not only do his effects still thrill in that enjoyable “Yuck!” way, but they add to the overall sense of danger and horror. Both films are notable for being well crafted, but Carpenter’s craft and sensibility are the right fit for this story, in all its gooey, goofy fun.