With Run The Series, The A.V. Club examines film franchises, studying how they change and evolve with each new installment.

Editor’s note: Beginning with this seasonally appropriate overview of the Hellraiser franchise, Run The Series officially becomes a staff feature, as opposed to a single editor’s semi-regular column. Cinema’s various sequels, prequels, and forced continuations are too much for one person to explore alone. And so from here on out, I’ll be one of many A.V. Club writers to tackle the twists and turns of various movie franchises. Hopefully, this will allow for a wider range of opinions, as well as more frequent additions to the feature. I’ll leave you now in the capable hands of the site’s resident Cenobite junkie, Katie Rife. —A.A. Dowd

Compared to the other famous horror franchises, your Freddys and your Jasons and whatnot, the Hellraiser movies are failures. Even the Child’s Play movies make Pinhead look like a nonstarter, grossing a total of $126 million to the Hellraiser movies’ $48 million. Yet, there are nine official Hellraiser movies—the same number as the far-more-profitable A Nightmare On Elm Street franchise—and a number of novels, comic books, and fan films building on its mythology.

Why? Because horror nerds, the kind of people who buy back issues of Fangoria and clap at a well-executed kill scene, fucking love the Hellraiser movies. Terminally serious and outrageously excessive, they separate the true fans from the weekend warriors. They are somber and violent and no fun on either an earnest or an ironic level. Yes, Hellraiser has its beloved tropes and corny catchphrases, but those are uttered with such conviction, and accompanied by such graphic nightmare imagery, that it feels perverse to cheer for them (not that that’s ever stopped Hellraiser fans). If slasher movies are the horny jocks of the horror world, Hellraiser is the humorless art student who wears a dog collar and black lipstick and prefers staying home and reading poetry to getting wasted at keg parties. Even when its ambition exceeds its budget—which is often—it’s trying to say something with its occult art projects.

Hellraiser is actively trying to alienate the casual viewer, using gore effects so intent on being extreme and transgressive that they occasionally tip into the absurd, like an Urban Dictionary entry describing some detailed and disgusting sex act that exists only in the mind of the kid who wrote it. Skinless people, rendered in bloody, anatomically correct detail, are a common trope, as are the ubiquitous chains with hooks on them, used to rip people apart in a process affectionately referred to in IMDB user reviews as “chaining.” The special effects and makeup are the real stars of these films, although as the sequels pile up and the budgets get slashed, the gore is gradually replaced with nudity, which, as a wise man once noted, is the cheapest special effect there is.

Speaking of freaking out the squares: Everyone makes a big deal about the Hellraiser movies being about BDSM, and they are, to varying degrees of bluntness. Most of your related subcultural tropes (needle-based or otherwise) appear at some point, and grotesque facial mutilations notwithstanding, Pinhead and his Cenobite pals would fit right in at a fetish club. Once he got there, however, Pinhead would probably corner a cute Fairuza Balk type and proceed to talk her ear off, because although he talks a good game about pain indistinguishable from pleasure, what he really likes is giving speeches. Pompous, professorial speeches suitable for a satanic reverend (they don’t call him the Pope Of Hell for nothing) are Pinhead’s speciality, and they always end just before our protagonist finally solves the puzzle box that will send him back to hell. (Horror is a very passive exercise in Hellraiser; climactic scenes consist mostly of characters watching in abject terror as some icky gore effect unfolds before their eyes.)

That’s not to dismiss Pinhead as a character. Being more verbose than Michael Myers and more earnest than Freddy Krueger has its benefits, and over the course of the series the Cenobite leader undergoes real character development from pure evil to conflicted antihero to vengeful demigod and back again. You can make a deal with Pinhead, and many try, although he seems particularly fond of spunky heroine Kirsty Cotton, played by Ashley Laurence in a career-defining role. That complexity is also reflected in the rules the Cenobites live by, which—at least in the earlier films where the internal logic remains sound (more on that later)—are more nuanced than the “sex=death” slasher code. The Cenobites only appear when they are called, and they are called by people who have experienced every earthly sensation and still want more. This is expressed in the Hellraiser movies as kinky sex, but it’s avariciousness, which could just as easily apply to drugs, that really does original depraved thrill-seekers Frank (Sean Chapman) and Julia (Clare Higgins) in.

But—and this is a big but—all that moral complexity and character development could also be read as inconsistency, especially in the later sequels. Hellraiser was low-budget from its inception, and the quality drops off sharply with the budgets of each successive sequel. Watching the majority of the Hellraiser franchise is a painful experience, and not in a way Cenobite freaks might like either. Only the first four screened in theaters, but a Hellraiser direct-to-video sequel came out every few years, kept alive by true believers with no choice but to take this shit seriously, from 1996 to 2011, when series star Doug Bradley declined to play Pinhead in Hellraiser: Revelations, effectively killing the franchise.

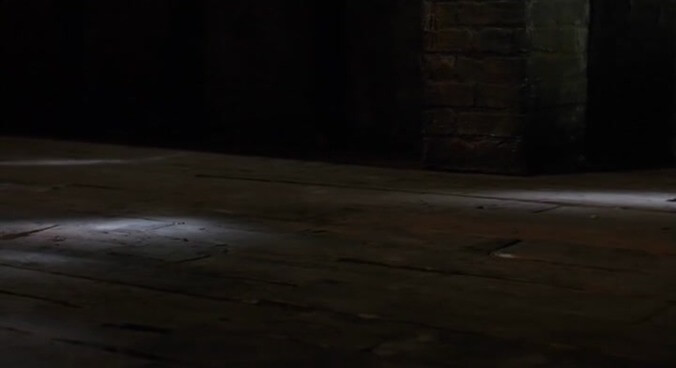

Watching the first Hellraiser (1987), it’s unclear whether Clive Barker was in step with the ’80s or if the ’80s were in step with Clive Barker, but either way it works. Barker loves soft focus, silk blouses, and doves, sensual imagery he contrasts with some truly gruesome special effects. The essential Britishness of the project shines through despite the best efforts of the producers, who went so far as to re-dub several of the actors—some of whom had to have been Shakespeareans in another life—with American accents. Ironic, really, that they were so concerned with driving audiences away with British accents and not with extreme gore scenes like this one, created with an additional $25,000 in funding acquired at the end of production:

That’s creepy pervert Uncle Frank, brought back to life by his brother Larry’s (Andrew Robinson) blood after being dragged to hell by the Cenobites for opening a forbidden occult puzzle box. Frank is assisted by Julia, his sister-in-law, with whom he had a heated affair right before her wedding to Larry. Julia brings Frank hapless businessmen she picks up at bars and dispatches with a hammer, leaving their corpses on the floor for her undead lover to feast upon. Needless to say, this behavior becomes difficult to hide after a while, and soon Larry’s daughter Kirsty, who appears to be in her early 20s, finds her uncle’s skinless-but-very-much-alive body in the attic. That’s when everything goes to hell, until Kirsty literally ends up in hell and AAAAAAAAAAHHHHHH what is that thing?!

The rest is easily available online, as well as in the opening scenes of the sequel, Hellbound: Hellraiser II (1988), which conveniently recaps the events of the first film using the old “survivor in a mental institution recalls the horrors of the first movie to a psychiatrist” trope. Barker relinquished directing duties to first-time director Tony Randel for the sequel, but the creative team was obviously very reverential of Barker and his baroque romantic-horror style is still very much prevalent. Even more so than the first film, the special effects are the stars of Hellbound, from the monster makeup on the Cenobites to a shocking tableau of mutilated corpses to the darkly beautiful matte paintings of hell itself:

All this is to create atmosphere, and Hellbound succeeds admirably in that respect. About halfway through, Kirsty and mysterious mute mental patient Tiffany (Imogen Boorman) leave the asylum and descend back into hell. Here the film takes a turn for the fantastic as Kirsty travels through different characters’ own personal hells, tying up loose ends from the first movie and eventually presenting Pinhead with yet another clever loophole to his stated deal of eternal torment. But, again, these confrontations are just vehicles for bravura special effects and artsy camera angles, which alternate between effective (the scene where the Cenobites welcome Kirsty to hell) and overwrought (the creation of Pinhead in the opening scene):

Hellbound ends with the creation of a tower that’s supposed to be the physical manifestation of Pinhead’s evil but looks more like a window display at a Halloween store, which is actually an acceptable apt segue into Hellraiser III: Hell On Earth (1992). This time Randel was replaced with yet another director, Anthony Hickox, whose previous credits included the first two Waxworks movies. This turned out to be a big change, arguably for the better. Hell On Earth lightens the tone considerably from the first two Hellraiser movies while still keeping the mythology (relatively) intact, and is the only one in the series that could be considered funny on purpose. The movie bears the distinct stamp of the early ’90s, most hilariously personified in three new Cenobites: A DJ with CDs stuck in his head, a bartender who spits fire, and this guy, who talks like Freddy Krueger:

Our heroine, Joey (Terry Farrell), is a reporter who can somehow afford a Manhattan apartment with a view despite working in journalism, which may have actually been possible in the early ’90s. Her investigation provides a convenient entrance into the story, which revolves around Pinhead’s soul fighting Pinhead’s body. Apparently the two were separated at the end of Hellbound and now his “evil” is walking around on its own, committing all manner of torture and blasphemy, which not only provides a central conflict but also justifies throwing away the concept that the Cenobites only kill those who ask for it, because he’s, like, pure evil now, dude. (This rule will continue to be broken throughout the rest of the franchise as sinners and innocents alike are dismembered for the Cenobites’ amusement.)

Hell On Earth oscillates wildly between campy fun and self-serious mythologizing—a perfect example is the excessive slaughter at the “goth” nightclub, where, by the way, the bartenders all wear tuxedos, a tone-deaf little detail that exposes the stuffy Britishness underlying the whole thing. Everyone is acting as hard as they possibly can, and snippets of dialogue sound like rejected first drafts of a True Detective episode: “There is a secret song at the center of the world, Joey, and its sound is like razors through flesh.” (Guess who says that.) Graphic scenes of people being skinned alive sit alongside ridiculous, greased-up sub-Cinemax sex scenes, and lectures on the nature of good and evil are given to a guy sitting on a bed literally covered in rose petals. And then there’s Pinhead’s blasphemous monologue in the church—watching the clip, keep in mind we’ve just seen a cop being killed by a CD that was flung at his head, which makes dialogue like this more difficult to swallow:

But then the end credits roll, and Motörhead starts playing “Hellraiser,” and for a moment all is right with the world. A giddiness sets in, which will be useful for the fourth film in the series, Hellraiser: Bloodline (1996), which is kind of a mess. (That’s not really the movie’s fault, though—originally intended to be an anthology film consisting of three storylines, it was cut down significantly for the theatrical release, with both explicit gore scenes and major plot points removed without the director’s consent. Thus, it is an Alan Smithee film.) But it’s an entertaining mess which many fans passionately defend, and even when it does cross the line into ineptitude, the result is good-bad enjoyment, not bad-bad boredom. Take Pinhead’s big “garden of Eden” speech—it’s bombastic, and, yeah, goofy, but c’mon, this is a great image:

The stories, featuring men standing around looking horrified instead of women for a change, flesh out (no pun intended) the back story of the Lemarchand family. First there’s toymaker Philip Lemarchand (Bruce Ramsay), who created the evil box—or the “Lament Configuration,” for the nerds—for an aristocrat obsessed with the occult in 18th century France. Then we’ve got architect John Merchant (Ramsay again), who battles Pinhead and a sexy female demon named Angelique (Valentina Vargas) in contemporary New York City. Finally, there’s the “Hellraiser In Space” segment, which takes place on a space station that looks a lot like every other space station in a mid-’90s sci-fi movie—let’s say Cyborg 2 with Angelina Jolie and Jack Palance.

That’s all great, but there’s something far more important about Bloodline that needs to be discussed, right now: Adam Scott, fresh off of his run on Boy Meets World, playing a decadent French aristocrat made immortal by black magic and probably maggots in his first film role:

At the end of Bloodline, Dr. Paul Merchant (Ramsay, a third time) folds Pinhead into a giant space-box and vaporizes him Death Star-style, an ending that is goddamn definitive. Bloodline also turned out to be the last Hellraiser released theatrically, and the last Clive Barker wanted anything to do with, both of which also seem like a hard “out” point. But never underestimate the resilience of a horror franchise—Pinhead’s ultimate demise takes place in the year 2127, giving future Hellraiser hopefuls 134 years of Cenobite history to work with.

That brings us to Hellraiser: Inferno (2000), the first of several low points in the series. At this point Kirsty’s out of the picture (at least temporarily), the original rules of Cenobite engagement are discarded, and Pinhead’s ultimate fate is sealed. So what’s left? You guessed it—a Gritty! Contemporary! Reboot!

Inferno marked the directing debut of Scott Derrickson, who would go on to do much better work on the Sinister movies. It’s basically a Seven “influenced” serial-killer procedural with some Cenobite stuff laid over the top, which is not a terrible idea on paper but is executed so poorly that it’s a chore to sit through. Star Craig Sheffer also starred in Barker’s Nightbreed, which is probably how he got the job, and chews the scenery with goofy rubber faces and bulging eyes.

Every sub-Bad Lieutenant cliché of the corrupt cop is here—Hookers! Cocaine! A long-suffering wife! A partner with a Brooklyn accent!—and from the first groan-worthy moment of voice-over through the inexplicably Twin Peaks-esque interlude at a cowboy bar to the ham-fisted symbolism of the ending, the only proper way to watch Inferno is with eyes rolled all the way in the back of your head. This might all seem appealing to bad-movie aficionados, but seriously, don’t open this box. (It took your author, numbed by over a decade of exposure to VHS trash cinema, two tries to finish it.) Here, here’s the big climactic reveal. Now you don’t have to see the movie. You’re welcome:

Perhaps the most offensive thing about Inferno is its seeming indifference to the larger Hellraiser storyline, a distinction that makes the sixth movie in the series, Hellraiser: Hellseeker (2002), slightly more palatable. The second and last in Hellraiser’s “cheating dirtbags get their supernatural comeuppance” cycle, Hellseeker at least tries to work itself into the larger Hellraiser mythos by bringing back Ashley Laurence as Kirsty. But like Inferno, it falls so far short of its ambitions that only the most dedicated and generous fan could give it the benefit of the doubt. One good bit of news, though: If you’ve ever wanted to see Dennis Duffy getting needles stuck into his brain, here’s your chance.

Dean Winters, perhaps looking to beef up his bank account as Oz drew to a close, stars as cheating dirtbag Trevor, which is a cheating-dirtbag sort of name. Sympathies for Trevor shift as rapidly as the storyline, which is trying to be a fractured, hallucinatory descent into madness but functionally serves as an all-purpose coverall for filmmaking mistakes. Pinhead is in full demigod mode here, screwing with Trevor’s mind in order to get to Kirsty, who has motivations of her own. None of this really holds up to close scrutiny—in fact, don’t start looking for continuity errors or logical inconsistencies in Hellseeker, or you will be the one whose tortured mind will step through the doorway into the realm of the insane.

Hellseeker director Rick Bota also directs Hellraiser: Deader, or “Hellraiser: Euro Edition,” released the same year as Hostel (2005). The script for Deader was reportedly bought as an unrelated spec and retrofitted to the Hellraiser franchise, which makes sense because, as in Inferno, the Cenobites feel incidental to the plot. Kari Wuhrer is doing her best as Amy Klein, another girl reporter, this one reduced to writing Vice-style articles called “How To Be A Crack Whore” because that’s the state of journalism these days. Amy owns no real estate—chain smoking and combat boots are all she has in this life.

Anyway, Amy is sent to Romania to investigate the “deaders,” a resurrection cult that also holds some bitchin’ Eurotrash sex raves on the Bucharest subway system. In the process she gets ahold of the famous box, which Kirsty apparently gave to the Salvation Army after the events of Hellseeker. Not that it really matters—there isn’t much Cenobite footage in this thing, and when they do appear, there isn’t enough money in the budget to mount a proper baroque gore scene anyway. Instead, we just get Amy thrashing around her hotel bathroom (it’s easier to clean up in there) with fake blood on her shirt.

At this point, it’s tempting to just give up. Hellraiser: Deader starts off okay—“hey, maybe this one will be decent,” you might think. “I like that Kari Wuhrer’s style.” But that’s just Stockholm syndrome, and after a tasteless and hacked child-molester flashback and some truly atrocious CGI in the confusing climactic scene, this is how you will probably feel:

But you’re so close. So close. You really have turned a corner, and although Hellraiser: Hellworld (2005) is also poorly made and tangentially related to the original Hellraiser at best, it’s also the point where the franchise embraces its destiny as direct-to-video filler and drops the artsy bullshit in favor of a straightforward “kids getting picked off one-by-one at a party” movie. And after the last three movies, that’s for the best.

Hellworld’s stated intention is to be a Scream-type self-aware take on the franchise, which is fine, except it really doesn’t work to have a character citing the “rules” of a movie series that has clearly not given a fuck about rules for the past five movies or so. But hey, future Superman Henry Cavill is there (British people being a Hellraiser rule that actually sticks, apparently), the bartenders are still wearing tuxedos, and hell finally got the Internet—only about a decade after the rest of us—and that’s all rather amusing.

Outdated Scream references aside, Hellworld’s main influence is torture-porn films of the Saw variety, splitting up the protagonists, all avid players of a Hellraiser-based MMORPG called “Hellworld,” so each can go through his or her blood-drenched dark night of the soul. (And lest we forget for a moment that this movie was made in 2005, a “can you hear me now” joke is there to remind us.) As far as the Hellraiser elements go, this is the laziest yet. You can practically hear the cash register ringing during each of Doug Bradley’s all-too-brief on-screen appearances. He’s not even the main villain of the piece—that role is filled, rather admirably, actually, by genre veteran Lance Henriksen.

This sort of cynical cash grab would be very upsetting to someone still deeply invested in the franchise, but at this point this writer only had one goal in mind: getting through 2011’s Hellraiser: Revelations’ (mercifully brief) 75-minute running time. Revelations completes Hellraiser’s transformation from an original and refreshingly adult concept into teens indiscriminately screwing and dying, hollowing out the soul of the franchise while functioning as a loose remake of the original. Shithead teenagers Steven (Nick Eversman) and Nico (Jay Gillespie) are poor substitutes for Frank and Julia, and an impassioned-yet-banal speech ripped from the pages of Fight Club toward the end of the movie may inspire wistful recollections of Pinhead reciting Bible verses in Hell On Earth. But honestly, this movie is not as bad as it could have been, irritating found-footage interludes excepted (those couldn’t possibly get much worse). At least the big twists don’t inspire derisive laughter like in some other Hellraiser sequels (looking at you, Inferno), and the bloody mattresses and skinless teens feel like old friends after the throwaway Cenobite scenes in Deader and Hellworld. None of it is very creative, but it’s faithful to the spirit—if not the letter—of the franchise.

So will Hellraiser survive to skin perverts alive once more? Not the way it’s currently going, and this is why:

Not that it’s Stephan Smith Collins’ fault that he isn’t Doug Bradley. He just isn’t Doug Bradley. He seems to know this, and doesn’t talk much, but even in the Hellraiser sequels’ most preposterous moments Bradley served as a sinister reminder of its past glory. That’s why, stripped of the last remaining link to everything that made Hellraiser intriguing in the first place, Revelations will be remembered as the film that killed the franchise—until the proposed remake, with Barker and Bradley reportedly both on board, makes it out of (development) hell.