With BlacKkKlansman, Spike Lee turns a dull memoir into an energetic crowd-pleaser

Film Features Blackkklansman

A few years ago, I wrote an essay bemoaning the way Hollywood explores the subject of prejudice. Too often, I argued, the films it makes are uplifting period pieces—Race, Get On Up, 42, The Help, Loving, Hidden Figures, etc.—which together suggest a world where racism is not only a problem from the past, but also one that’s been solved.

Happily, this is one trend that’s since shown signs of improvement. Boots Riley’s satire Sorry To Bother You is one of the most talked-about films of the summer, and The Purge series, along with mega-blockbusters Get Out and Black Panther, have demonstrated the interest, if not the outright hunger, that audiences have for contemporary stories grappling frankly with social issues.

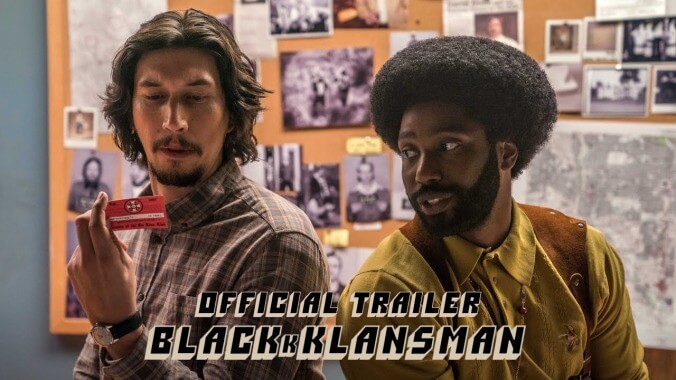

Straddling these two ideas is Spike Lee’s BlacKkKlansman, based on a memoir by Ron Stallworth. The film is a crowd-pleasing and often riotous tale of a black police officer (played by John David Washington) who goes undercover via phone in the Ku Klux Klan in 1979 Colorado Springs, gathering information on the organization and essentially trolling “Grand Wizard” David Duke. (Flip Zimmerman, a Jewish cop played by Adam Driver, acts as Stallworth in face-to-face meetings.) It ends with justice largely being served, as some Klan members get killed or arrested in a botched terrorist attack, while a racist white cop is also taken down, his arrest enthusiastically backed by the police force.

At the same time, the relevance of the film’s themes to modern America are repeatedly stressed; not surprisingly, Lee refuses to pretend that racism is no longer an issue, particularly in today’s political environment. He includes multiple references to the Trump era, some explicit, others only loosely disguised—Klansmen chanting, “America first,” and calling to take the country back and “achieve its greatness again,” a prediction that a demagogue would one day smuggle white supremacist ideology into the White House through the dog-whistle issues of crime, immigration, and tax reform. The ending cuts directly from the Klan burning a cross to real-life footage of the 2017 Charlottesville riots, where the latest generation of racists chanted against Jews and Black Lives Matter, and a woman protesting them was killed. Trump refused to condemn the white nationalists; David Duke was thrilled.

There are a lot of differences between Lee’s film and Stallworth’s book, but the shift in tone is what lingers the most. The memoir is a fairly dry procedural, a short (under 200 pages) and somewhat superficial account of the case, with a few detours to provide the history of things like the KKK in Colorado. There’s an undercurrent of progress and optimism, perhaps reflective of the fact that it was first published in 2014, back when today’s world would’ve seemed like some pessimist’s fever dream.

The film, in contrast, bursts with personality, color, and an energetic editing style that packs the story with both anger and humor, even pausing for a quasi-dance sequence at one point. But while Lee undoubtedly relished the satirical possibilities of the premise, he seems less interested in the police material than he does in telling a story that underlines how racism—established, organized, institutional racism—has always pervaded American culture.

The film’s first shot is a clip from Gone With The Wind, still the highest-grossing picture of all time (adjusted for inflation), and one depicting the Confederacy as a great lost civilization and slavery as no big deal. It then cuts to Alec Baldwin making a Klan recruitment film and flubbing his lines. Another, devastating sequence cuts between the Klan’s rapturous enjoyment of Birth Of A Nation and a man (played by Harry Belafonte) recounting how that film’s massive success resurrected the KKK’s popularity, leading to a childhood friend being tortured and lynched. In another scene, characters discuss Blaxploitation films and the need for both diversity in cinema and positive depictions of non-white characters.

The theme of pop culture intersecting with politics, along with the premise and the film’s looseness with facts, sometimes make BlacKkKlansman feel like a Spike Lee version of Argo. That also depicted an undercover operation with an irresistible hook, a subterfuge that went so smoothly that the director felt compelled to add scenes of conventional drama. Lee’s additions are far more comprehensive than Ben Affleck’s, though they seem more justifiable; while a different Argo director could’ve made its ending suspenseful without resorting to an invented car chase, Stallworth’s memoir suggests there’s not a ton of narrative meat on his story.

The sequence where Stallworth serves as Duke’s bodyguard—despite having repeatedly conversed with him on the phone, in a disguised voice—actually happened, but otherwise the closest thing the book gets to a tense moment is when an undercover cop accidentally writes his own name on a Klan application, and has to get another copy without anyone discovering why. In the film’s equivalent, a suspicious Klansman wants Zimmerman to take a polygraph and bare his penis (to prove he’s not Jewish), among other tests of loyalty. Even setting aside how editing, suspenseful music, and acting can juice up a scene, the scenarios in the film are just more satisfying from a thriller perspective. An adaptation that changed nothing would’ve felt thin, if not outright dull.

BlacKkKlansman’s inventions include not just most of the plot, but also a good number of major characters (putting something of a lie to the film’s assertion that it is based on some “fo’ real, fo’ real shit”). To start, there’s Patrice Dumas (Laura Harrier), the president of the college’s black student union, whose vocal politics make her a target for harassment from both the Klan and cops. She and Stallworth inch their way into a relationship, one complicated by her blanket distrust of policemen and the lies necessitated by his undercover assignment. (When Stallworth begins his assignment in the book, he’s just started dating the woman who would become his wife, but she’s not a character.) She’s also there to give the opposing side in a variety of debates, including on whether the black community should try to change the system from within or abandon it entirely.

Lee also dramatizes the Klan side of things. Duke is all too real, but the film expands the role of Walter (Ryan Eggold), the leader of the local chapter, who seems committed to following Duke in putting a friendlier (to whites) face on the organization. At one point, he nominates Zimmerman as his successor; this happened in real life, but Walter is a much more distinct presence in the film, as his literary counterpart barely gets any dialogue. Meanwhile, Walter’s right-hand man, Felix Kendrickson, is a wholesale addition to the story. He’s the central villain, the Klansman who is both the most suspicious of the new guy, and the one most eager to commit acts of terrorism. Most of the meetings take place at his house, where his wife, Connie, traipses about with snacks and tries to participate until he screams for her to leave. Pretty much any scene with Felix (Jasper Pääkkönen) is stomach-churning, none more so than a moment of quiet pillow talk that would be affectionate, were he and Connie not horrible bigots.

The climax of the film revolves around the Kendricksons. He builds a bomb and has her plant it at Dumas’ house; when she’s unable to, she hides it in Dumas’ car instead. When Felix parks next to the car to detonate it, he ends up killing himself. Again, they didn’t exist so the poetic justice of this moment didn’t happen. (“I knew I’d rewrite it before [producer Jordan Peele] sent the script, ’cause if the script had everything there, he wouldn’t have called me,” Lee remarked in a recent interview.)

At the end of Stallworth’s memoir, he writes that his investigation came to little when measured by the concrete metrics of arrests or convictions. Where it added value, he contends, is in what it prevented: “As a result of our combined effort, no parent of a black or other minority child, or any child for that matter, had to explain why an eighteen-foot cross was seen burning at this or that location—especially those individuals from the South who, perhaps as children, had experienced the terrorist act of a Klan cross burning.”

For Lee to make the investigation a more concrete success is a curious choice. No doubt some of it was related to the necessities of storytelling—a film doesn’t need a villain or a climax, but it’s hard to have a cop thriller without either—and it’s likely he simply took pleasure out of depicting Klansmen as so stupid that they can’t help but blow themselves up. Still, it’s an unusual moment of optimism for a director whose films this millennium have been about how major institutions like pop culture (Bamboozled), capitalism (She Hate Me), government (When The Levees Broke), and the military (Miracle At St. Anna) have failed huge swaths of the country because of racism. Even though it’s followed by a real-life modern-day montage, which extinguishes any pleasure that had been in the film, Lee finishes the story he’s been telling by implying the system worked, when we all know it doesn’t.

Start with: Honestly, the book isn’t great. This story would be better suited to a magazine article or told to another writer who could beef it up with stronger characters, a sense of pacing, and just flat-out better prose. Here’s a representative passage of Stallworth’s tepid writing, about black cops being seen as traitors to the race:

[They became] a black Judas who had chosen to collaborate with the governmental ‘massa’ (master) and enforce the ‘white man’s justice.’ We had become slaves to the ‘system,’ the white man’s ‘boy,’ as I was called on many occasions during my career by my self-proclaimed black ‘brothers.’

But even if the book were better, the film would still be one of Lee’s strongest in ages, less messy than recent entries, if less ambitious overall (but don’t listen to me; I think Miracle At St. Anna and Chi-Raq are underrated, and that She Hate Me is one of his best of the past 20 years). I can’t remember the last time an ending packed such a wallop, particularly the ending to a “comedy.” Go see it, for the sake of your country. Then go vote.