A new biography explores the rebellious, bohemian life of the author of Harriet The Spy

Aux Features Book Review

The 1964 children’s novel Harriet The Spy inspired an entire generation of future writers and diarists. The protagonist—an Upper East Side 11-year-old who spies on her neighbors when she’s not spending time with her stern, knowledgeable nanny, Ole Golly—stood out from the idyllic young heroes and heroines of children’s literature of the era. Harriet was opinionated, sneaky, and stubborn, and rebelled against her parents’ demands. “I’ll be damned if I go!” she says of attending dance school.

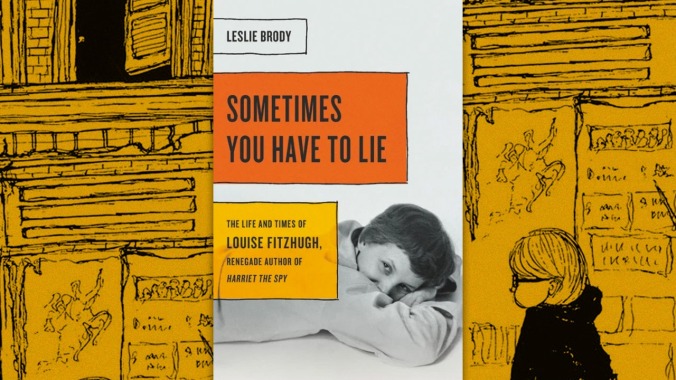

It turns out many of the roots of Harriet’s privileged existence can be found in the life of her creator, Louise Fitzhugh. Leslie Brody’s new biography, Sometimes You Have To Lie (a piece of Ole Golly dialogue), delves deep into the writer’s fascinating past. Fitzhugh was the product of a short-lived, tempestuous union between Millsaps Fitzhugh and Mary Louise Perkins, which started via a shipboard romance during the Roaring ’20s. The two soon realized they were ill-suited for each other, resulting in a fierce custody battle of baby Louise. Mary Louise had no chance against the well-off and established Fitzhugh family (Millsaps was a prominent Memphis lawyer), and as a result did not see her daughter for several years. Like Harriet, Fitzhugh was mostly raised by nannies and other house staff.

The young Louise apparently suffered few ill effects from this unconventional upbringing, and certainly no damage to her self-esteem. From the earliest of ages, the petite, pretty Southerner was steadfast in her opinions, caring little for what others thought. In the mid-century South, despite a series of male suitors (including one annulled marriage when she was underage), Fitzhugh primarily dated women. Rebelling against the white-glove, bridge-playing society in which she’d grown up (and which she would reference in Harriet), Fitzhugh kept her hair short, wore men’s clothing, and made no secret of her sexuality at a time when few queer people could afford to do so. As she told one male date who came to pick her up for a dance, “I am not going to join those menstruating minstrels.”

No doubt, Fitzhugh’s financial stability made it easier for her to flout convention, and to escape her Southern upbringing. Brody enthusiastically describes Louise’s thrilling adventures on ocean liners to Europe, hanging out in Parisian cafés and painting in Bologna, before moving to Greenwich Village. There she cultivated a social circle that included like-minded artists, including children’s book author Maurice Sendak, playwright Lorraine Hansberry, and future fellow YA author Marijane Meaker (known as M.E. Kerr), who remembers that Louise was “always herself, never in the closet.” Her girlfriends were similarly ambitious, like her first love, Amelia Brent, who wound up working at Time magazine; soap opera actress Constance Ford; and Alixe Gordon, who became a prominent casting director.

Brody performed detailed research via newspaper clippings, correspondence, and a variety of interviews, and her descriptions in Sometimes You Have To Lie can get downright granular. “They shopped for furnishings at antique stores and flea markets, bought a lot of flowering plants, and set a dozen avocado pits to germinate around the house,” Brody writes of Fitzhugh and Gordon’s cluttered apartment near Fourteenth Street. The author paints Fitzhugh as compassionate but someone who didn’t suffer fools, and who worked almost constantly, even though her initial creative output leaned more toward painting than writing.

The publication of Harriet The Spy, Fitzhugh’s most famous and successful work, changed the trajectory of her life. She was no longer financially dependent on the family she otherwise had little use for, though it also brought her fame, which she wasn’t much interested in, shunning the book tours and interviews that would usually accompany such a sensational release. Harriet The Spy was not only a huge hit with booksellers, children’s librarians, and middle-school readers all over the country; it’s now credited with helping to create an age of New Realism for children’s literature, paving the way for authors like Kerr, Paul Zindel, and Judy Blume to craft imperfect protagonists for younger readers. “I don’t think it was her love for children, particularly, nor her identification with them that made her such a natural writer,” Kerr said of Fitzhugh’s approach. “I think it was more her insistence that children were people, not to be talked down to, patronized, or treated as some special group. The notion that children were people was a rare one, in those days, in our field.”

The publication of Harriet is both climactic and anti-climactic in Sometimes You Have To Lie. Fitzhugh’s story grows somewhat sadder as she tries to top her greatest success—publishing the less-well-received quasi-sequel The Long Secret the following year, and releasing a too-graphic anti-war picture book in the Vietnam era. Brody doesn’t hide her disdain for Fitzhugh’s final partner, Lois Morehead, the most domestic of the writer’s lovers, who made a home for them in suburban Connecticut. Following Fitzhugh’s fatal brain aneurysm, at the age of 46, there was no discussion of her lesbianism at the memorial, which Morehead organized, in direct opposition to the open way the writer lived her life.

Brody makes the case that the life Fitzhugh was able to craft can be listed among her most impressive creations: devoted friends, one long-term romance after another, and the will to never compromise over who she was—neither regarding her sexuality nor anything else. It makes the biography’s title puzzling. The true heart of Fitzhugh’s life can be found in what Ole Golly says after that line: “But to yourself you must always tell the truth.” In Sometimes You Have To Lie, Brody shows that Louise Fitzhugh certainly did so, offering Harriet The Spy fans even more to admire.

16 Comments

Harriet’s more than “imperfect’, she’s a creepy voyeur who doesn’t get half the comeuppance she probably deserves. I love this book so much, I love the dubious morality of it and central character who’s both lovable and detestable (both so rare in a kids book), I love the world it creates that may not have ever existed like that but certainly has nothing to do with the NYC of today.

Well that’s the wonderful thing about the word “imperfect” it can cover all manner of flaws and character defects.My sister was a devoted Harriet the Spy fan, I’ll have to tell her about the new book. I always love discovering the lives of authors were more interesting than expected.

Sure, it does, but there’s more to it than that. Judy Blume’s central characters are imperfect but usually fundamentally decent. Harriet is really up to some shady business and could at least be called amoral. The lessons she learns are actually pretty adult and involve navigating relationships and putting her interests to use in more socially acceptable ways… But I don’t really think she walks away learning a moral lesson or changed for the better in the way the lead of kid’s story usually would be. I’m probably not expressing it well I guess.

Blume’s books were clearly happening in the real world of their time and were intended to be lessons about real world problems — sibling rivalry among children, the confusion between love and lust that teenagers often have, etc. So the central characters tended to be somewhat bland as the reader was supposed to see themselves in that role. Harriet isn’t supposed to be a realistic story and she is more of an anti-hero.

No I get you. I agree with you, I think. The dubious moral nature is in many ways more of a teaching tool for what it feels like being in the adult world, if not exactly realistic in the exact depiction. I mean being “moral” can be challenging, and a lot of young people are skilled at some dubious stuff, figuring out how to make that work as the consequences get more and more serious is a good lesson for kids.In some ways, the decency of some central characters is the biggest fictional elements in children’s fiction. I like that Harriet is kind of shitty, but good at what she does, and learns that it’s better for her and everyone to learn how to turn her hand at things people will respect (but are still fulfilling to her). It’s been a long time since reading it, but in reading over the wiki write up, I noticed this: Ole Golly tells her “you have to do two things, and you don’t like either one of them. 1: You have to apologize. 2: You have to lie. Otherwise you are going to lose a friend.” This is good advice, but I’m not sure it’s the moral lesson other children’s books would give. It’s, as you said, a very adult lesson.But I think a major part of growing up, and becoming an adult, is learning that imperfection comes with the package, and striving to make your imperfect make up mesh with and benefit you and the larger society. I also think it’s a good way of looking at how you deal with what some people consider a shitty person. Like, most Kid’s books (or adult books for that matter) would just tell you to be better, empathize with your fellow humans and so on, but that’s rather pat, and more difficult for some than others. It’s “Do better.” instead of “Be better.” and one of those is far more achievable than the other. In the end it’s better if you do good, it doesn’t really matter if you believe, or agree with the moral reasoning of why it’s good.

I don’t really think she walks away learning a moral lesson or changed for the better in the way the lead of kid’s story usually would be.That seems part and parcel with the whole idea that Fitzhugh’s unique insight was that “children were people.” Not just recognizing that children themselves are often immoral or amoral in terms of her character development, but giving young readers enough credit to assume they can identify amoral/immoral characters/actions as such without a lot of hand holding or preaching.It’s definitely rare these days (and in earlier/19th century children’s lit), but I feel like it was more common in the 60s and 70s. Turtle from The Westing Game is another example that comes to mind.

Yes, I read this book when I was a child. Of course, all of the architecture was foreign to me, Australian houses in the north then were mostly plasterboard and wood, single or double story. But I do remember the climbing through walls and fire escapes spying on other inhabitants in the building, a bit creepy for a little girl to do, not to mention immoral and actually illegal according to property/privacy law. I guess that’s how kids learn about the world, but even so.

The book is 100% on Harriet’s side, though: basically it’s saying “Here’s what it means to be a writer.” The biggest lesson she learns is the title of this biography, and it’s a pretty tough one.

Ever read “The Long Secret”? It was billed as a HTS “sequel” so I snapped it up at like 11 years old. It takes place in the aftermath of Harriet having become a social pariah in the wake of being found out, though the viewpoint quickly shifts to that of her one friend not to totally cut her off, and becomes about that friend’s experience of her first period. I remember reading this as an adolescent guy and being all “hey! This Harriet The Spy sequel is actually all about periods!” but looking back on it, it was probably good for me to have read it, and an omniscient-viewpoint inner account of that experience is probably a good thing in general for guys that age to read.

I did read it but don’t remember it well! I think the story blurs in my mind with “Shelia The Great” and “Superfudge” as “East Coast Summer Vacation Stories About An Era Before My Time.”

So, it really IS very much like real life, then.Even as a boy in an age very different from today’s, this was a deeply-influential story for me: my fifth-grade teacher, who was really an absolute prick otherwise (I overheard my parents, who rarely bothered to judge others more than momentarily, joking repeatedly and derisively about him after a student-teacher conference), read this to us.I need to read it again. It’s been at least twenty years since I read it to my younger son.

A fantastic modern successor to Harriet the Spy is Rebecca Stead’s Liar & Spy, in which a kid who moves into a new apartment meets a Harriet-like “spy” that’s convinced that one of their neighbors is a serial killer. Having someone roped into the game rather than focusing squarely on the “spy” makes a huge difference in terms of the tone, and it also has a great example of an unreliable narrator for young readers.

I love finding out that the creators of things that were deeply formative were also queer. It’s like there’s some frequency we all pick up on, even when you’re too young to know how or why.

Arnold Lobel (of Frog and Toad fame) and Maurice Sendak have folks covered on the picture book and early reader front.

Lobel, I KNEW it! I adored and devoured them as a little reader, and just a few years ago I was like – oh, of course they were partners (as well as being best friends). It all came back to me, how Toad was so highly strung, and Frog was always there for him, taking it in stride, taking care of him, Toad knowing how much he needs him, etc, etc. Of COURSE they were a couple, who’d been together a long time, I mean, clearly!Sendak I picked up on a loooong time ago, reading In The Night Kitchen for the first time…oh, I got it.

Is there a name for the genre of upper-class girls living in New York City with nannies? Kay Thompson’s Eloise books are another entry in the genre.