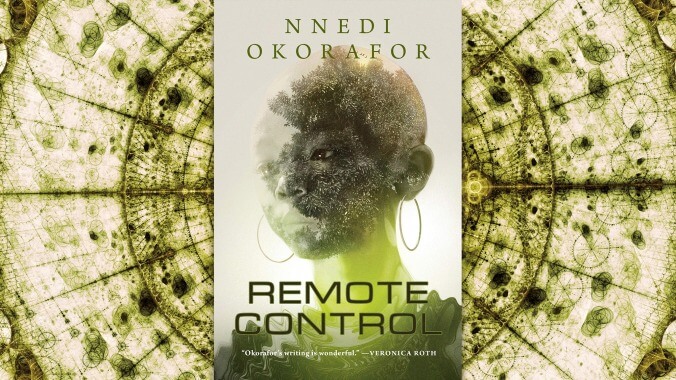

A young girl acquires deadly power in Nnedi Okorafor’s latest sci-fi journey

Aux Features Book Review

A wanderer with terrible power, Sankofa, the protagonist of Hugo Award-winning author Nnedi Okorafor’s latest novella, Remote Control, has the aura of a mythological figure. She inspires a mix of hope and fear everywhere she goes, and there are numerous conflicting tales about who she is and what she’s capable of. But while the people she interacts with call her the adopted daughter of Death or a witch, Okorafor most directly compares her to the stick-up man Omar Little from The Wire. Okorafor uses Omar’s taunting line to his enemies—“You come at the king, you best not miss”—as an epigraph. People mark Sankofa’s appearance in town by shouting, “Sankofa is coming,” a riff on the warnings that greeted Michael K. Williams’ shotgun-wielding robber of drug dealers. The Wire was known for its gritty realism, and Okorafor evoking the series in her latest work of Africanfuturism and mythology produces a unique tale of how legends are made.

Sankofa was once a sickly, mythology-obsessed girl named Fatima who loved to spend time in her family’s backyard shea tree looking at the stars and drawing messages she saw written in the dirt. When a meteor shower brings a green seedlike rock hurtling into the roots of her favorite tree, it bestows Fatima with the strange power to glow with a terrible radiation that kills any living thing.

Remote Control combines plot elements from two of Okorafor’s previous novels wherein a young girl discovers she has magical powers, Akata Witch and Who Fears Death, with the genre bending of Lagoon, which featured both gods and aliens. Titled after the Ghanian slang for witchcraft, the novella follows Fatima as she assumes the name Sankofa and begins wandering throughout Ghana looking for answers, purpose, and peace.

Always on foot because her powers also disable any machine she touches, Sankofa occasionally evokes the trope of the disguised god who expects to be welcomed into homes or the Western hero perpetually wandering into trouble before hitting the road again. Sankofa uses her power to bring peace to the terminally ill and to defend herself from those who might prey on a girl traveling alone, earning herself a reputation as both an angel of mercy and a spirit of death that must be appeased with her favorite offerings, including lukewarm orange Fanta, goat meat, and tailored clothes.

In Okorafor’s vision of a near-future Ghana, the new clashes with the old, from wealthy American families bringing their children home to grudgingly learn their heritage to the devout wife of a town’s imam who programmed a robot defender to prevent traffic accidents. It’s a world of dirt roads navigated by self-driving vehicles and mud huts equipped with electricity and TVs, and one with so much potential that it feels like it deserves more time.

This is also true of Remote Control’s story and characters. Sankofa suffers from the same problems of impassive Western heroes and unknowable mythological figures, coming across as a force of nature as much as a character. She’s most sympathetic before she gains her powers, when she’s just a curious and mischievous child delighting in hiding from her parents and infuriating her brother. But as she loses everything over and over again, her pain and forced distance from other people make her feel as alien as the source of her abilities.

Omar became a legend within The Wire’s version of Baltimore because he was a perpetual underdog, a fierce and canny figure fighting against the might of the city’s biggest gangs. Sankofa’s incredible power makes her untouchable, and the larger, hinted-at enemy of the LifeGen Corporation—a powerful pharmaceutical company searching for aliens, which is also featured in Okorafor’s 2016 novel The Book Of Phoenix—never manifests in any satisfying way. Sankofa is often both the victim and the aggressor, and her greatest struggle is one of self-control as she strives to protect herself without causing too much collateral damage.

While the book is full of powerful lines, like when the owner of an electronics store boldly confronts Sankofa by saying, “I like to look into the eyes of hurricanes,” Remote Control reads much like the books of mythology Fatima loved. The novella provides poignant expressions about grief, longing, growing up, and facing your past, but offers little explanation of why things happen or don’t. The ending in particular feels rushed, with a climax that’s meant to be dramatic but is more perplexing.

Sankofa gets her powers from a radioactive rock and is accompanied by a fox who’s mysteriously immune to her glow, straddling the line between comic book hero and a witch with a familiar. Okorafor has never felt a need to place her stories firmly into conventional genres, but given how short and fascinating Remote Control is, she could have done more to refine this work. Sankofa’s story feels complete by its end, making it unlikely that Okorafor will use Remote Control as the start of a new series. Standing alone, Sankofa is a fascinating character, but one whose legend isn’t quite compelling enough to take hold in our world.

Author photo: Colleen Durkin

2 Comments

WIREstarter

Twisted wire ….starter?