HBO oral history Tinderbox offers little more than amusing anecdotes

James Andrew Miller interviews dozens of key players from HBO’s past for his 1,024-page book, but can’t weave them into a cohesive whole

Books Reviews HBO

The HBO series Vinyl seemed destined for success. Created by Martin Scorsese, Mick Jagger, and Terence Winter (who’d served as executive producer of The Sopranos and creator of Boardwalk Empire), the 2016 show centered on the exploits of a 1970s record executive. The pilot was directed by Scorsese. Its cast wasn’t star-studded in the same way a series like Big Little Lies’ was, but Bobby Cannavale, Olivia Wilde, and Ray Romano weren’t nobodies. Yet Vinyl failed. Why did it fail? That depends on who you ask, but nobody disagrees. It failed.

The lesson that Casey Bloys, the current content chief at HBO and HBO Max, took from the experience was “there’s nobody above the law, there’s nobody who can’t make a bad show.” Even with all the right tools, sometimes you can’t create something worthwhile. A useful way, perhaps, of thinking about Tinderbox, an oral history of HBO from journalist James Andrew Miller, whose previous subjects have included ESPN and Saturday Night Live.

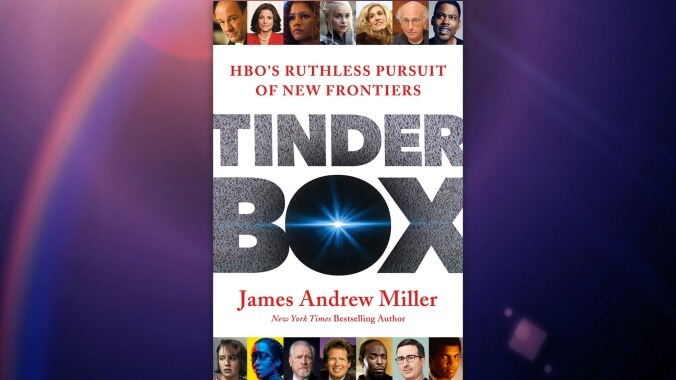

The massive, 1,024-page book is built on interviews of dozens and dozens of key players in HBO’s past. There’s Edie Falco and Laura Dern. Davids Chase, Simon, and Larry. There’s executive after executive after executive. Miller did an exceptional job getting important people on the record and at length.

That, unfortunately, is only half the job, and often the better you are at it, the harder the other half of the job—putting the book together in a cohesive way—gets. There is so much ground to cover, from 1971 to the present day. Organizing it all so that it flows well and gives readers the context they need is a gargantuan task, and Tinderbox doesn’t come close to fulfilling it.

There are a number of amusing stories for fans of HBO’s biggest hits. A standout is J.B. Smoove’s account of his Curb Your Enthusiasm audition. He recalls walking in and saying, “Okay, Larry, let’s do this baby, and since this is improv, I might fuck around and slap you in the face.” But that story is quickly followed by a section that exemplifies the book’s flaws.

Less than a page later, there’s a quote from John McEnroe about his appearance on the show. “When I saw the outline, I thought, ‘How the hell can somebody even come up with this? This guy’s out of his mind.’” That is immediately followed by bolded, italicized transitional text about a former executive returning to the HBO building because they were naming a theater after him. If you’ve never seen Curb or perhaps don’t remember the plot of a television episode that came out 14 years ago, Miller won’t help you. He never explains it.

This quick gloss is not in exchange for depth in other areas. Little in this book rises above the level of trivia. Did Michael Imperioli have a driver’s license when he started on The Sopranos? He did not. Tom McCarthy, writer and director of Spotlight, directed an unaired Game Of Thrones pilot. It never saw daylight because it was, apparently, horrible. But there’s little more detail than that.

The book is most engaging when it reveals the odd way executives think about the art of television. One example: In the late ’90s, HBO was developing a movie about the slave ship Amistad at the same time Steven Spielberg was developing his own. Because HBO was on track to release its film first, Jeffrey Katzenberg, then head of DreamWorks, called and asked new CEO Jeff Bewkes if HBO would drop the project to make way for Spielberg. Bewkes was hoping HBO’s version would compete for an Emmy, but recalls thinking, “If Steven thinks he can do for civil rights with Amistad what he did for anti-Semitism with Schindler’s List, we should hold back with our modest megaphone.” It’s got a nice ring to it, though it’s unclear just what he thinks Schindler’s List did for anti-Semitism or how Amistad could do the same for civil rights.

A more sinister turn occurs during the making of Westworld. Miller writes that creators Lisa Joy and Jonathan Nolan encountered resistance on one particular artistic decision: putting “faces in the foreground of scenes involving nudity.” Instead, “HBO would push back, asking for closeups of breasts and other body parts.” Worse, on a conference call, “an executive accused Joy of having a ‘girlish’ fantasy about how great ‘gentle sex’ could be.” This incident gets the rare-in-Tinderbox treatment of anonymizing both Miller’s source(s) and who that source was talking about.

An odd feeling builds throughout the book that Miller is protecting certain executives and the myth of HBO more generally. He tells the story of Chris Albrecht, the chairman of HBO who lost his job in 2007 after he was arrested for grabbing his girlfriend by the wrist and throat in Las Vegas. In the wake of this news, the Los Angeles Times reported that this wasn’t his first alleged offense: In 1991 HBO had paid a $400,000 settlement to a subordinate with whom Albrecht was “romantically involved” because he allegedly shoved and choked her. That chapter ends with a chorus of his colleagues opining about how everyone makes mistakes. Later, Miller refers to it as that “crazy night in Las Vegas.”

Similarly curious is Miller’s presentation of an instance regarding then-chairman Michael Fuchs’ decision to fire Bridget Potter, a senior vice-president. Then-HR chief Shelley Fischel said, “There have been instances when I believe HBO terminated women in a way that reflected a male perspective on employment… For women, Michael was not easy to work for.” The only follow-up to this is Potter calling Fuchs “an equal opportunity bully.” There is no way to know the reason for the absence of further comment. Did nobody have anything else to say? Did Miller not ask, or did he just leave it out?

Here, the overall surface-level nature of Tinderbox is a mark in Miller’s defense; he skimps on details everywhere, not just on workplace discrimination and sexism. At least his interviews have produced a nice volume of anecdotes to share at parties.

11 Comments

But does he interview classic AV Club gimmick commenter HBO CEO of Tits? If not, no sale.

I thought it was “VP of Tits”.

No, they wouldn’t trust a lowly VP with such a central aspect of TV production. Shame he’s not involved. I can only guess that he was approached but was too overcome with smutty laughter at the phrase ‘oral history’ to take part.

I noted how a show like the recent HBO show White Lotus would have had the CEO’s mark all over it 15 years ago instead we got a close up of Steve Zahn’s swollen balls, a guy eating another guy’s ass and the same guy taking a dump into a suitcase. I’m not sure this is an improvement.

I have to mention he is in there as the Deep Throat (as it were) source of many of the stories…..

“HBO oral history Tinderbox offers little more than amusing anecdotes”

Oral history is oral history.

Well that’s disappointing. I’ll certainly still read this–it’s probably the closest thing we’ll get to a comprehensive history of HBO–but I can see how this project might test the limits of Miller’s oral history format. It worked well in his ESPN and SNL histories because there are countless funny, insightful personalities to interview for those. For HBO the key sources are going to be mostly execs and producers, not the most interesting bunch.I browsed this a bit yesterday and thought the section on At&t’s absorption of HBO was really good, but I noticed it leaned more on Miller’s own prose than his work normally does. So I’m getting the impression that this would have worked better as a narrative history.I’ve always thought Albrecht’s firing, however deserved, marks the point where HBO starts its decline, as it started chasing tentpole blockbusters and gradually reigning in some of the creative freedom they used to allow creators. Now it’s become pretty much Netflix with a spot of legacy prestige. Curious if the book takes a similar tack. At the very least, it was interesting being reminded how important sports and concerts were to HBO even up until the early 2000’s. I kinda miss that.

Miller’s CAA book was maybe a sign of things to come here. I haven’t read this yet and probably won’t, but he’s definitely never been able to pull things together into a narrative, or do something like Bill Carter did with his late night books.

totally agree on the (yes well deserved) firing of albrecht being a significant turning point for HBO. its hard to describe how different and unique the network was from about 1999-2007, and how important being the kid in the neighborhood with HBO was for said concerts and sports events.

basically, i wish carnivale could have continued, that boardwalk empire and deadwood could have told their entire stories, and that we still had the kind of HBO that cancels a high viewership comedy show because the critics hated it (lucky louie)

OK so I did read this, and sad to say this review is absolutely correct. If you are a fan of any HBO show you’ll learn nothing about it; all the anecdotes are familiar. But if you’re interested in the intricate ins-and-outs of the executive suite, there’s a lot in here for you, lots of painful details about who had what responsibility and who they reported to and who they didn’t want to report to and on and on. Actually one ongoing thread concerning Sheila Nevins’ work as chief of HBO’s Documentary programming was legitimately interesting, showing how her passion for the genre shaped the network. But everyone else disappears in a cloud of expensive suits.

I agree with this review. I can’t help but note that Miller’s two strongest books, LIVE FROM NEW YORK and THESE GUYS HAVE ALL THE FUN, had Tom Shales as co-writer. I’m now wondering if Shales was the Marc Caro to his Jean-Pierre Jeunet — the creative partner who held everything together.

I think the book had way too much on the business — there was no need for anything not about the programming itself, and the book could’ve started in 1992, with THE LARRY SANDERS SHOW and OZ. Or with FRAGGLE ROCK. But yeah, Miller’s really bad at transitioning between sections. It’s like he was overwhelmed by the material.