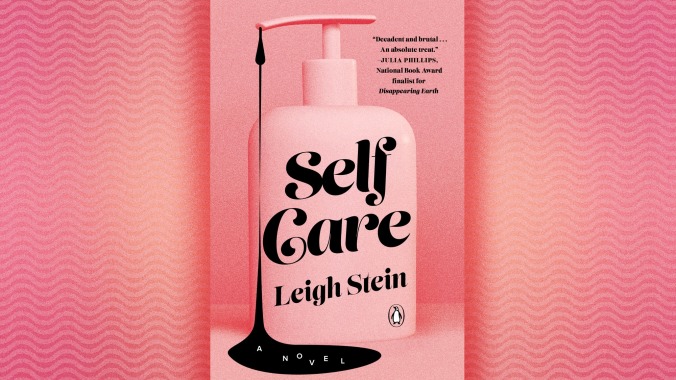

Self Care is a timely beach read that skewers wellness and performative feminism

Aux Features Feminism

Has there been a more corrupted term in recent years than “self-care”? What used to be a battle cry of resistance for Black and queer social justice activists, has morphed into a buzzword meant to sell expensive face creams, a yoga retreat in a five-star hotel, and any product that inches you closer to whatever conventionally attractive, almost-always white influencer is currently staring into the horizon on your Instagram feed. The ink spilled over self-care, both in its watered-down and original versions, has been clickbait for an abundance of think pieces in women’s media outlets. It’s powered the $4 trillion wellness industry, another misnomer if there ever was one. There’s even a self-care tag on the humor website Reductress. A satirical novel on the co-optation of the term by our consumer-based society is probably long overdue. Self Care, the fourth book by writer Leigh Stein (Land Of Enchantment, The Fallback Plan), is here to fill that void.

The novel opens with Maren Gelb heading to a remote cabin for a digital detox. Her tweet about the president’s daughter has landed her in hot water with the Secret Service, the social media mob, and her company. As the COO of Richual, a self-described inclusive, feminist social media app devoted entirely to wellness and self-care for women, her attack on any woman is seen as fodder for controversy. CEO Devin Avery is mostly annoyed that this exploded right before their next round of seeking funding, while Khadijah Walker, the overworked SVP of editorial strategy, is hiding a secret that might put her job and financial future in danger. As the three women do damage control on both their company and their personal lives, they are left to decide whether they are ready to practice what they preach—and post.

Self Care is the bitchy beach read for people who wear a “Bitches Get Shit” done T-shirt, but who are also well-versed in debates about reclaiming the word “bitch.” Stein is the kind of writer who would be at home both in The New Yorker and on a Tumblr page devoted to writing poems about The Bachelor. It’s no wonder she has crafted a book that is extremely readable, often laugh-out-loud funny, and loaded with pop culture references, internet lingo, Instagram hashtags, and every major and minor viral scandal of the early Trump years. This isn’t to say it’s pure fluff, though you’d be forgiven for thinking it, it’s such a quick read. At its core, it’s a very clever satire, sometimes a bit too smug, but with a deft hand behind it. It’s a novel that asks, what happens when we care so much for ourselves that we stop caring about anything else except our own perfectly-manicured preservation?

It is also a very anti-capitalist book, reserving its most biting criticisms for some delicious send-ups on how the wellness industry has preyed on women’s insecurities and deprived them of real empowerment. In one chapter, Maren describes the questionnaire she’s devised to mine personal stories from influencers to garner more likes. It includes asking about deaths of loved ones, abusive relationships, addictions, mental illness, and sexual assault. She finishes it off with “bonus points if you could reveal something from your past and at the same time raise awareness about trans issues or police brutality against POC or the anniversary of 9/11.” It’s an effective indictment of a trend that’s been around since the blogosphere: the commodification of women’s trauma in exchange for ad dollars.

Nuggets like these are a big draw. Maren throws herself into Richual as a way to ignore the reality of Trump’s America. Devin’s devotion to maintaining her good looks as some sort of feminist ploy—“If we can alter our bodies, we can alter our potential” is one of her mantras—is actually nothing of the sort. Khadijah is keenly aware of the performative aspects of allyship in companies that take care to schedule ethnically diverse stock photos but won’t pay employees what they’re worth.

That having been said, the character of Khadijah is one of the weaker spots in the novel. While it takes a few chapters for Maren and Devin to evolve from ridiculed archetypes, Khadijah is written earnestly from the get-go—a savvy move, given she is the one Black character in our trio of narrators. She can be just as ambitious and sly as her bosses, but her motivations and her own underdog position make it easy to root for her. On the other hand, this gingerly approach to her point of view means there is less of it as the story unfolds, and she ends up being somewhat drowned out by the other two, white narrators. It’s a solid attempt, but Khadijah’s presence in the book never fully transcends the white feminism™ it purports to.

The book also loses some of its punch when its attention turns to Evan Wiley, a Richual board member accused of sexual misconduct. The #MeToo movement is the major backdrop of the novel, and it propels a lot of the action of the second half. Still, there was so much rich material left to explore within the screwed-up dynamics among the women themselves that an easy male villain doesn’t seem necessary. Self Care goes for breadth in scope and can sometimes mimic the breaking news overload of social media platforms.

The ending is unsettling and hints at a much darker subtext than the previous pages revealed. It’s as if Stein put on her own sunbathed filter, preferring to keep the tone bright through most of the book until the very shadowy finish, and one wishes it would have emerged earlier. There is a morality tale here, though, in between all the LOLs. At its best, it reminds us that the whole point of self-care is to replenish ourselves for a larger, communal fight.

9 Comments

I suggest the term “self-defense” as a replacement. Its long history and association with violence might make it a bit harder to turn into a face cream. Also means the same damn thing.

“…people who wear a “Bitches Get Shit” done T-shirt…” you might want to move those quotation marks over a bit although the typo makes me laugh!

What used to be a battle cry of resistance

“Self care” is a much lamer battle cry than “Spoon!”

I miss the Tick

I’ve personally always been a bigger fan of “Not in the face! Not in the face!”

“While it takes a few chapters for Maren and Devin to evolve from

ridiculed archetypes, Khadijah is written earnestly from the get-go—a

savvy move, given she is the one Black character in our trio of

narrators. She can be just as ambitious and sly as her bosses, but her

motivations and her own underdog position make it easy to root for her.On the other hand, this gingerly approach to her point of view means

there is less of it as the story unfolds, and she ends up being somewhat

drowned out by the other two, white narrators. It’s a solid attempt,

but Khadijah’s presence in the book never fully transcends the white

feminism™ it purports to.”This criticism feels half-baked; when I try to parse it, I don’t actually know what it’s trying to say. There’s no clarity in the terms here. What is a “gingerly approach” to Khadijah’s point of view? Is her character handled “gingerly”? Is that somehow different from handling her character “earnestly”? How precisely is her voice drowned out? Does she just get less page time? Is her plot arc less impactful, or sidelined? And is Khadijah’s presence in the book really meant to “transcend” white feminism? I suspect that actually, Khadijah’s presence in the book is to provide another perspective from which to critique white feminism & the self-care industry.

Perhaps Stein doesn’t carry this through to the end of the novel— maybe the other plot developments, in which Khadijah doesn’t have as much of a role, take over, and so the critiques offered by Khadijah’s perspective are lost, or less potent, and this is a missed opportunity for the book. But then say that clearly.

Have you read the book? I can’t tell from your commentI just finished the audiobook and I have to agree with Ines. I get that “gingerly” isn’t the most precise term so I’ll try to explain how the criticism rang true to me. Khadijah’s voice feels much less developed that Devin and Maren. It‘s just weird the books most likable narrator didn’t have a huge amount of depth when the motivations and general fuckedupness of the white narrators were central to their narratives. If all three narrators were developed more uniquely the contrast wouldn’t have felt off balance.Her biggest impact on the plot is literally in the last chapter but because of her lack of development my reaction was, “Meh”. It could have been much more interesting with a touch more insight.

Despite all this I actually enjoyed the book. It was the kind of on point snark I needed while folding laundry. It just could have been even better.

Definitely sounds like a book and an author Katie Herzog would love. And she does!

It sounds like a fun read. For what it’s worth the term self-care started in the medical and mental health field, as a recommendation for certain patients (those with PTSD, the elderly, those recovering from certain ailments) and for medical and mental health professionals as a way to avoid burn out.

It then got embraced by the Black Panthers and the women’s movement as a way to fight for a more just medical system and equality (one that didn’t ignore the health needs of women and POC).

But for all sorts of folks to currently use the original idea, to take care of yourself so you don’t have burn out or get re-traumatized by certain situations, seems a good thing.

The Goops of the world and others seem a ripe, if easy, target, but as long as its funny and well written, I’m in!