Escapism has long been a driving tenet of comic books, but as the medium has evolved, creators have started to see the value of comics as tools to create empathy and put readers in another person’s experience. 2017 was a year in which the world could have used a lot more empathy, and some of the best comics and graphic novels highlighted the importance of understanding other worldviews and seeing the value in different perspectives.

There was still plenty of escapism for when current events became too much, and the best of those stories still had personal angles and distinct styles that made them stand out. The year’s big comic trends were visually inventive coming-of-age stories, action extravaganzas across an array of genres, and a lot of books that tackled the major political and social issues of 2017. Over in the realm of superheroes, Batman reigned supreme—which is fitting considering DC’s Metal event is about a bunch of evil Batmans taking over the Multiverse—and familiar favorites like Ms. Marvel and Squirrel Girl reminded readers why they still demand attention.

While reading great comics is the true reward, The A.V. Club received the Eisner Award for Best Comic-Related Journalism/Periodical earlier this year, which is pretty damn cool. We’re, like, authorities now. If you invite us over for brunch and your bookshelf doesn’t have our picks for the best comics of 2017, we can write you a citation. Each Eisner Award-winning critic outlines their individual picks for best comics of 2017 below.

Oliver Sava

2017’s biggest success story came from a 55-year-old cartoonist making her graphic novel debut. Emil Ferris’ My Favorite Thing Is Monsters (Fantagraphics) deserves every bit of attention it has received from the art community and mainstream press. Drawn in ballpoint pen on lined notebook paper, this oversized book features the kind of artwork that forces the reader to stop and savor the details. The intricately cross-hatched artwork is paired with two powerful coming-of-age stories, one set in 1968 Chicago, the other at the start of the Nazi regime in Germany. These threads intertwine in ways that illuminate both of the characters, the book offering a devastating look at how intolerance takes hold of communities and crushes the human spirit.

Tillie Walden’s Spinning (First Second) also featured a young woman discovering her place in the world, with Walden recounting the end of her time as a competitive figure skater during her teen years. It’s a much softer tale with a smaller scope than Ferris’ work, and Walden puts the reader deep into her personal experience with delicate character work and compositions that reflect her mental state at the time. She emphasizes both the pain and the exhilaration of her coming out, tenderly exploring a difficult period of her past to realize that she made the right decisions, no matter how much they may hurt in retrospect.

There were a lot of outstanding coming-of-age comics this year, and Shade The Changing Girl (Young Animal/DC Comics) and Crawl Space (Koyama Press) take a psychedelic approach that makes these self-discoveries as visually striking as they are emotionally rich. Shade writer Cecil Castellucci simultaneously addresses the identity crises of adolescence and one’s late 20s by having an adult alien possess a teenage mean girl’s body, and that dynamic becomes complicated by a third entity representing an elderly desire to return to youth. The human perspective is much more extreme than what Loma Shade felt on her home world, resulting in trippy layouts from Marley Zarcone and brilliant color work by Kelly Fitzpatrick, with the experimental visuals accentuating Loma Shade’s alien nature.

Jesse Jacobs’ Crawl Space vibrates with raw artistic energy. By arranging thin bands of rainbow colors in intricate patterns, Jacobs creates different illusions of movement, oscillating between structure and chaos. Teenagers discover a beautiful fantasy world of unusual shapes and colors by traveling through a washing machine, and for the main character, spending time in this environment permanently alters her worldview. The challenges of adolescence are interpreted through Jacobs’ surreal sensibility, and he has an insightful, bittersweet perspective of teenage solitude and embracing what sets you apart rather than trying to fit in. This message is inspiring but it’s also a little sad, acknowledging the inevitable loneliness of an isolated life.

When it comes to immersive settings, few comics can match Julia Wertz’s Tenements, Towers & Trash (Black Dog & Leventhal), a mix of prose, illustrations, and short comics that form an unconventional history of New York City. There’s no overarching narrative, though the preface invites the reader to look at this book as a love letter to the city Wertz lived in for years before rising rents and shady landlords forced her out. Her meticulous renderings of New York City throughout its history spotlight her commitment to honoring the past, and delving into the lesser-known corners of the city gives readers a comprehensive tour of an environment that is constantly changing.

Sometimes you just want to read something that will make you happy, and Giant Days (Boom!) provides a monthly dose of good feelings with the hijinks of housemates Daisy, Esther, and Susan. Living together introduces new stresses for the university BFFs, while learning about the ongoing struggles of adulthood provides a constant stream of personal drama balanced by heightened comedy. Max Sarin’s exaggerated characterizations and sharp timing amplify the humor of John Allison’s scripts, and every issue is guaranteed to have multiple laugh-out-loud moments, even when the subject matter gets serious.

Marvel had a rough year with the misguided Secret Empire crossover and the uninspired Marvel Legacy event, but the bright spots in the publisher’s lineup continued to shine. Ms. Marvel (Marvel) tackled major social and political issues more directly and with more nuance than books like Secret Empire, Captain America, and Champions, and writer G. Willow Wilson created riveting superhero stories revolving around online bullying and xenophobia. Ms. Marvel had some of the most affecting moments in superhero comics this year: students rallying around Becky with support after she’s outed online by a literal troll; the tragic destruction of a neighborhood mosque; Kamala getting a visit from Lockjaw when the world looks especially hopeless. Even with multiple artists, the book’s visuals have always maintained a youthful energy that is amplified by Ian Herring’s vibrant coloring.

Since it debuted in 2015, The Unbeatable Squirrel Girl (Marvel) has consistently been one of Marvel’s most clever and inventive series, and this year saw writer Ryan North, artist Erica Henderson, and colorist Rico Renzi reaching new highs. Squirrel Girl and friends faced off against an evil tech genius that controlled animals via implanted microchips and traveled to the Savage Land for a story that combined computer programming and dinosaurs, but the best issues barely featured the lead character. A Brain Drain spotlight story offered a hilariously nihilistic take on superhero life, and the issue modeled after a zine had an astounding group of creators offering their unique interpretations of the Marvel Universe.

Deathstroke (DC) is a very different superhero comic, one that is rooted in traditional superhero storytelling and complex continuity. Christopher Priest is giving a master class in how to streamline established character history for a fresh perspective that still respects the past, and he’s taken Slade Wilson to fascinating new places. Last year had Priest establishing how much of a jerk Slade is, but this year saw him revealing the villain’s vulnerability before giving him a spiritual experience that inspired him to try and become a hero. The book is an in-depth character study that isn’t afraid to ask big questions about superhero morality, and Priest’s scripts bring out the best in his collaborators by having them focus on more intimate storytelling. The moments of action are spectacular, but they have a clear emotional drive because of the character work that surrounds them.

That balance of action and character can also be found in Extremity (Image) and The Old Guard (Image), two new series that delivered breathtaking action sequences in service of stories about the emotional toll of prolonged violence. Daniel Warren Johnson and Mike Spicer’s Extremity threw readers into a war-torn fantasy world in which a young artist is forced to fight after losing her mother and her drawing hand to her tribe’s sworn enemies. The massive fight sequences are so thrilling that it’s easy to hope for a never-ending war, even with the devastation it wreaks on the heroine’s family. For the immortal soldiers of Greg Rucka, Leandro Fernandez, and Daniela Miwa’s The Old Guard, life actually is an eternal war, and this series uses Rucka’s deep knowledge of military history to add substance to a breakneck thriller. Fernandez’s hard-hitting artwork is paired with a surprisingly light pastel palette from Miwa, which brings out the strength of Fernandez’s inks while differentiating the series’ visuals from other action titles on the stands.

David Rubín is an artist who is always looking for new ways to use the comics page to depict space, movement, and the passage of time, and his Beowolf (Image) graphic novel with writer Santiago García is an ambitious retelling of the classic story. Rubín’s artwork refreshes the legend, while García’s script gives him the freedom to think outside the box and push himself to explore different visual approaches. Rubín has had an amazing year with Beowulf, Ether, Black Hammer, Sherlock Frankenstein And The Legion Of Evil, and the second volume of Rumble. The quality of his art is even more impressive considering the size of his workload.

Caitlin Rosberg

It’s been a busy year for Batman, which has meant a lot of good things for Batman books. These days, there’s a version of the character for nearly every taste, and while some of those versions have been easy to pass on, others have become must-reads for all the right reasons. With his time at the helm of the Batman juggernaut during the New 52, Scott Snyder is no stranger to the characters and ideas that he explored in All-Star Batman (DC), but focusing on Alfred Pennyworth and stepping back to let Raphael Albuquerque’s incredible art take center stage made the “First Ally” arc something really special. Much like his take on Jim Gordon as Batman, in “First Ally” Snyder slowly unwrapped an action-packed and arrestingly emotional story that firmly shows that the character’s strength lies in the family he’s built over the past near century.

Snyder is not alone in turning to Batman’s roots for new material. Returning to the radio dramas that spawned modern superheroes as we know them, Steve Orlando worked with Snyder and artist Riley Rossmo to create a team-up between two of the best detectives of all time in Batman/The Shadow (DC). Just half of a partnership between DC and Darkhorse, which owns the rights for Lamont Cranston’s alter ego, Batman/The Shadow was exactly the kind of self-contained adventure that makes else-world comics so great. It’s appropriately campy and a little overblown, just like the acting that defined radio dramas like The Shadow, and chock full of Easter eggs for Batman and Shadow fans alike. DC’s lineup has been lacking something since Rossmo’s run on Constantine ended, and his work alone makes the book good, but Orlando and Snyder’s willingness to lean into the inherent silliness and decades of canon that define these two characters is what makes it great.

Talking about the Batman successes without mentioning “The War Of Jokes And Riddles” arc in Tom King and Mikel Janin’s Batman (DC) run would be criminal. King managed to make a convincing Batman romance, a feat unto itself, but the skillful non-chronological unfolding of the narrative prompted an outpouring of emotion and empathy for Kite Man, of all characters. King is, for lack of a better phrase, the king of crafting tragic, nuanced, compelling stories that shift in scope, timeline, and morality without losing the specific narrative. Not only on Batman, but also on Mister Miracle (DC) with Sheriff Of Babylon collaborator Mitch Gerads, King has shown his skill is difficult to underestimate, and demonstrated his ability to work with really talented artists to make something that not is quite like what anybody else is making.

Warren Ellis’ Shipwreck (Aftershock) feels like the ragged, intoxicated uncle of King’s work, with sharper teeth and cynicism. Ellis has been staying busy with a lot of things other than comics, but 2017 saw him involved in a couple of notable titles and Shipwreck rises to the top. It’s the kind of cerebral, rambling, introspective work that Ellis really excels at when he’s not working with someone else’s intellectual property, and Phil Hester’s fractured, saturated art helps make sure the title doesn’t pull any punches. It has the same feel as some of Ellis’ best prose like in Normal and The Gun Machine, and it’s great to see that kind of work in comics again.

Redlands (Image) is one of the real standouts, once you dig past more recognizable characters and names. By Jordie Bellaire and Vanesa Del Rey, Redlands fills the holes left by the end of Clean Room and the slow publishing schedule for Bitch Planet. It’s tempting to say that Redlands is a combination of Southern Bastards and Black Magick, a Southern gothic horror tale about witches who come to save a town from itself. But Bellaire and Del Ray have spun a story that’s intensely gratifying in completely different ways, with beautiful violence and brutal art that doesn’t flinch from the world as it is. Although this is her first solo foray into writing, Bellaire is at the top of her colorist game in Redlands, and she and Del Ray have created something meaty and necessary.

Independently published comics and webcomics continue to flourish, and a lot of readers are rightfully turning to them to find content that doesn’t show up on the shelves of local shops. In the case of Not Drunk Enough (Oni), creator Tess Stone built an audience online and Kickstarted a print edition of the first volume before getting interest from a publisher. Not Drunk Enough is probably best described as Resident Evil meets Parks And Rec, an office-based horror comic that’s sometimes a comedy, complete with a motley crew of characters and evil corporate overlords. Stone’s sense of humor and skill with saturated colors along with his sketchy, dynamic art style make the comic a joy to read. Like Not Drunk Enough, Pascalle Lepas’ Wilde Life (webcomic) has a strong, dynamic cast of characters, but rather than being spooky, it’s a slice of life with a supernatural twist. Lepas has been working on webcomics since 2003, and her storytelling skills have never been better. Wilde Life is populated by a found family of lovely people, tied together by curiosity and a desire to protect one another from the things that go bump in the night.

When it comes to LGBTQ romance and erotica, Letters For Lucardo (Iron Circus Comics) blew the rest of the competition out of the water this year. It’s no surprise, given Iron Circus’ reputation for identifying and cultivating a roster of really talented creators and getting their work in front of a larger audience. Noora Heikkilä created a vampire story that’s sweet and emotionally evocative enough to overcome even the most cynical reader’s genre fatigue. It’s not uncommon for vampire romances to be May-December ones, but in Lucardo’s case, the human half of the couple is the one who is more physically aged. The story is short, but rich with detail and world-building, and Heikkilä’s skill with expressions and body language are a little overwhelming; tears and smiles are outsized and telegraphed, like Miyazaki characters, but blood-thirsty.

One of the real standout books this year is one that straddles the line between graphic novel, children’s book, and educational textbook. Abby Howard’s Dinosaur Empire: Earth Before Us (Amulet Books) is the best of all three types of books. Although Howard’s art style when it comes to humans is rounded, simplified, and a little cartoony, she depicts the flora and fauna of the era of the dinosaurs with scientific accuracy. Treading in the footsteps of The Magic School Bus, Howard uses an enthusiastic and well-versed adult character to guide a less than pleased kid through time-traveling adventures all over the world. Her excitement reinvigorates the kind of unabashed love for science and dinosaurs that so many people have as kids but lose somewhere along the way, bridging the gap between grown-ups and children in a completely organic way; it’s a true all-ages book.

Shea Hennum

2017 was a year of fracturing—from the cracking mask of Hollywood’s superficial and performative liberalism to the political tribalism that saw both major political parties factionalizing. We saw cultural institutions and icons in a new light. And we saw this balkanizing wave reflected in the year’s comics.

Sometimes this took a deadly serious form, as in the case of two memoirs, Pretending Is Lying

(New York Review Comics) and The Best We Could Do (Abrams). The former is Sophie Yanow’s translation of Dominique Goblet’s autobiography. Splintered into shards of memory, Goblet’s recollections are experienced as a stream of consciousness, each moment rendered in a coarse, abrasive tone. Ever dynamic, Goblet’s aesthetic moves between the experimental to the conventional, from the naturalistic to the stylized, from the juvenile to the refined. Each moment serves as a discrete savory morsel; but knocked around by the fragments on either side of it, each scene turns so you can see it from a new angle, revealing a morose, tragic core.

In much the same way, Thi Bui relates her memoir by weaving memory within memory to fracture the reader’s subjectivity, and she reveals a deep emotional truth about the narrative by infinitely rerouting the so-called objective truth. Drawn in an almost stereotypically “literary” style—thick lines, watercolors and ink washes, simple compositions, a vague attempt at a slightly heightened naturalism—Bui tells the story of her childhood, her parents’ childhood, and their lives as refugees displaced by the Vietnam War. In subject matter and style, The Best We Could Do recalls a number of contemporary autobiographical comics successes—Fun Home, Stitches, etc.—but Bui elevates her work by bringing a significant amount of attention to craft to refine and sharpen the telling of the story.

But the fractious zeitgeist also manifested in more irreverent ways. In

(Retrofit), art comics favorite Yuichi Yokoyama tells an opaque and vague story of a group of people entering a bar. The characters are nonexistent and the plot infinitely less so. The real draw is Yokoyama’s unique brand of cartooning. Eschewing all but the most pro forma hints of narrative, Yokoyama is concerned with atmosphere, space, tension, mood, and how those ambient feelings can be physicalized. The whole thing feels like a snippet (or fragment, if you will) of a lengthy, rich series that exists somewhere out in the ether, and it will leave readers pleasantly bemused.

Likewise, Zonzo (Fantagraphics) by the Spanish cartoonist Joan Cornellà chops up the narrative form and plays with it sadistically in his series of gross-out, maybe-deep comic strips. Even readers unfamiliar with his name will have seen Cornellà’s work before, as it circulates frequently throughout meme culture; and here he collects a number of his nonsensical comic strips that so perfectly fit the niche Cornellà himself essentially invented: charming, cleanly drawn, disturbing, disgusting, and genuinely funny.

(Drawn & Quarterly) by Michael DeForge, which was covered in more detail earlier in the year, is similar to Zonzo, as it features its author working at his peak, producing material that is so unique that it honestly feels like an artifact from another dimension.

This kaleidoscopic vision of American life of 2017 was also reflected in dark, probing explorations of fear, unease, and trauma in the anthology Mirror, Mirror II (2d Cloud), edited by Sean T. Collins and Julia Gfrörer, and Anti-Gone (Koyama Press) by Connor Willumsen.

Both titles are different in form—Mirror, Mirror II being an anthology-like mix of comics, illustrations, and prose from a variety of different authors, with different visions and different aesthetics all tied together with the tacit theme of sexuality and violence; Anti-Gone, on the other hand, was produced solely by Willumsen, and it tells the vague story of two figures sailing across a vast ocean and then getting high in the rundown ruins of some future mega-city. Like Mirror, Mirror, Anti-Gone is a visually rich text that brings in elements of humor, science fiction, horror, and comedy to tell an opaque story that both gives nothing of itself away but entices you to return to it again and again. With beautiful line art, Willumsen tells one of the oddest stories of the year, but also one of the most visually compelling and formally striking.

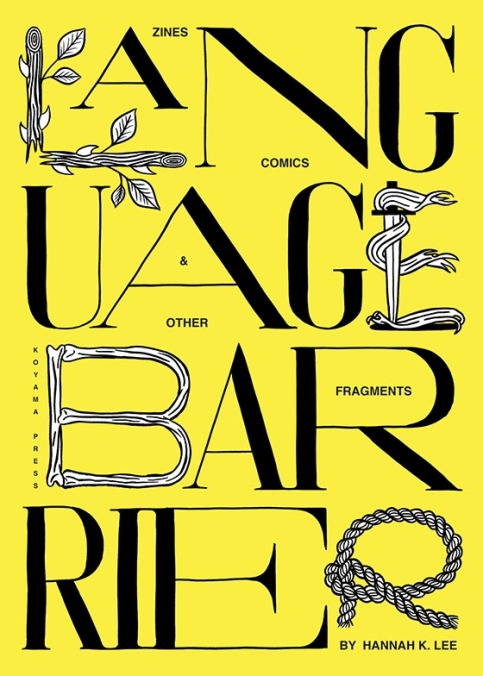

And finally, Hannah K. Lee’s Language Barrier (Koyama Press) represents a formal fragmentation. A collection of previously published zines, mini-comics, and illustrations, Language Barrier features “fragments” in the subtitle, and this is a good way to describe the makeup of the book. The narratives are discrete and self-contained, but they are bombarded on all sides by these interstitial asides—illustrations or short comics that intrude on the reading experience, disrupting it briefly with an artistic cacophony only to deposit you back on track. Beautifully rendered in a variety of aesthetics, Lee delivered a book best experienced across a number of brief-but-satisfying readings.

While stability would have been a more comfortable zeitgeist this year, cartoonists rose to the challenge and successfully captured the collective mood in unsettling and rewarding ways.