The Cult Of We expertly charts the disastrous arc of Adam Neumann’s WeWork

Wall Street Journal reporters Eliot Brown and Maureen Farrell explain, better than anyone else, how the real estate company ballooned to a $47 billion behemoth

Books Reviews WeWork

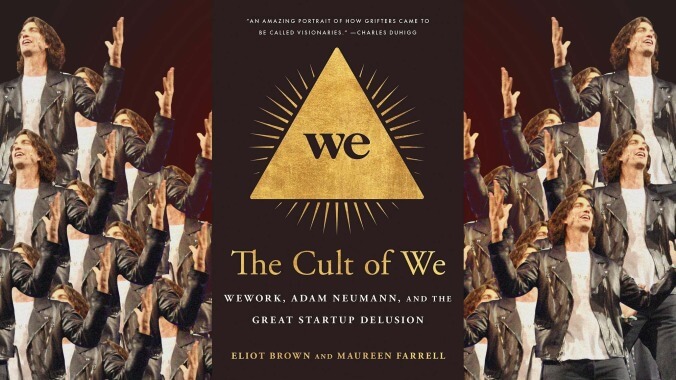

Not even two years after WeWork’s spectacular collapse, its story has been told numerous times. In January of last year—only three months after the company’s disgraced founder and former CEO, Adam Neumann, was ousted—there was a podcast series on the debacle hosted by former Marketplace host David Brown. In October 2020, New York Magazine reporter Reeves Wiedeman published his book, Billion Dollar Loser, an engaging profile of Neumann and the company. And this March, Hulu released a dreadful documentary, WeWork: Or The Making And Breaking Of A $47 Billion Unicorn. Into this saturated market, Wall Street Journal reporters Eliot Brown and Maureen Farrell, who cover start-ups and IPOs respectively, are publishing The Cult Of We: WeWork, Adam Neumann, And The Great Startup Delusion. Thankfully, being first isn’t always better.

The coverage of many Silicon Valley companies, even (and especially) in their demise, tends to center on the personalities of their founders. This makes a certain amount of sense and coincides with such leaders often being given too much power despite not being very good at their jobs. In this regard, Neumann is as desirable a figure as they come. He turned a successful office rental business into a massive, directionless corporation. He is married to Gwyneth Paltrow’s cousin. He got a sizable investment from Ashton Kutcher, who he met through The Kabbalah Centre. He really loves smoking weed. Even in the context of the young Silicon Valley elite, he sticks out as a uniquely entitled, uniquely childish, uniquely stupid man. Most importantly, maybe, he’s tall. (All books about start-ups, including this one, love mentioning how tall people are.)

There’s plenty of information about Neumann’s exploits in The Cult Of We, but what’s included is not merely titillating trivia. It’s not immaterial, for example, that Neumann once told the Crown Prince of Saudi Arabia, Mohammed bin Salman, that the two of them, along with Jared Kushner, were going to remake the Middle East, or that he said a Middle East peace treaty would be signed in a WeWork office space. Brown and Farrell also detail reports from those who managed Neumann’s private flights, which included one trip where passengers spit tequila on each other and another where “there was so much Marijuana smoke in the cabin that the crew was forced to pull out the jet’s oxygen masks and put them on.” A fine-in-theory ban on meat at WeWork was a hard sell, as Neumann barely talked to anyone who would be tasked with managing the initiative before he made the announcement; what’s more, his constant use of private jets and multiple cars undermined the environmental commitment that originally allegedly motivated the ban.

But the real meat of The Cult Of We, and what sets it apart from previous recitations of this story, is the skill and clarity with which Brown and Farrell describe the economic and financial environment that made WeWork’s absurd peak valuation of $47 billion possible in the first place. Prior accounts tend to zero in on the head of Softbank, Masayoshi Son, the man famous for losing more money than anybody ever had (approximately $70 billion in the dot-com bubble) and who remade his fortune via an early investment in Alibaba. Son invested $2 billion at WeWork’s top valuation. One frequently repeated anecdote goes that Son asked Neumann, “In a fight, who wins—the smart guy or the crazy guy?” Neumann, to Son’s satisfaction, said “the crazy guy.” But, Son explained, Neumann and his cofounder Miguel McKelvey, “are not crazy enough.”

A lot of blame for WeWork’s unfocused, overly aggressive strategy lies at Son’s feet. But what Brown and Farrell crystallize are how the distorted incentives and reckless decision-making by numerous well-monied people set WeWork on its doomed path. They highlight the disconnect between the venture funds that historically paid for start-ups’ private periods and the mutual funds at firms like Fidelity and T. Rowe Price that supercharged WeWork. The financial corporations doled out sums that dwarfed what many venture firms would consider, and their eagerness to not get left behind in the start-up bonanza clouded their judgment. Banks like J.P. Morgan Chase were so avid to get WeWork’s IPO business—which would lead to a windfall in fees—that they were willing to lend both WeWork and Neumann absurd amounts of money, spurring on the company’s absurd behavior. The board, the people whose responsibility it should have been to rein the company in, was more focused on getting a gigantic injection of cash from Softbank that would have allowed its members to cash out their shares at a huge profit; when that failed, they pushed for an IPO to get themselves the same.

Brown and Farrell’s big-picture view charting the arc of the company serves them well but lost is any real impression of what it might have been like to work there, especially at a level lower than an executive. Some examples, like a lament that high-ranking officials sometimes had to fly coach, elicit scoffs. The glimpses one gets of those below the C-suite, including a manager who was fired because they left one of WeWork’s mandatory hard-charging festivals early, suggest a disturbing situation, but The Cult Of We only scratches the surface.

Still, Brown and Farrell’s book provides essential insight into the opaque mechanics of how a private company builds astronomical valuation, and the twisted feedback loop that motivates people not to solve obvious problems. There is little indication that any powerful players have actually learned their lesson here, but at least we’re now better equipped to understand their mistakes.

Author photos: Eliot Brown (Photo: Andrew Kwok) and Maureen Farrell (Photo: Brie Anderson)

25 Comments

Adam Neuman strikes me as just another a con man/hustler/phony that got lucky, not as lucky as Zuckerberg but not as unlucky Billy McFarland of Fyre Fest. He, after all, walked away with a fortune. However, people really, really, really hate him enough that exposing him/trashing him has become a cottage industry when I am guessing 95% of people who don’t live in a major city have never heard of the guy or WeWork. He’s just punchable, that’s all.

That’s an oversimplification. The dude did actually run a reasonable portfolio of commercial real estate that he leased out and by all accounts made plenty of money doing it. The thing is though, running a commercial real estate portfolio is a very different game than what he tried to do with WeWork.

I just recently read the Billion Dollar Loser, but now I’m kind of wishing that I had waited to read this one instead.

My challenge with BDL is that while it does touch on the distortion of it all, it also didn’t for my taste dig enough into those larger impacts. Bad Blood, the Theranos book, is one of my favorite non-fiction books in ages and what I think it succeeds in really well is that while Theranos is an extreme example of a faulty system, it does still manage to convey how it illustrated all those fault lines in the current start-up approach. Something BDL really struggled with for reasons I didn’t at time get.

If you haven’t, check this out in terms of a “holy HELL this industry is fucked” narrative: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/House_of_Cards_(Cohan_book)Great story of how Bear Stearns went from one of the most aggressive and feared financial management companies in the world to a memory over the course of a long weekend.

Why did you find the Hulu documentary dreadful? I enjoyed it, but I admit it’s my only real exposure to the WeWork story so I really can’t say if it’s slanted towards someone. However, it does seem to answer the questions you had after reading this book, namely “what was it like to work there?” (Answer: fun! Until it absolutely was not.)

Agreed. That hulu doc was great.

Yeah, I dug it well enough. Maybe the focus on the CEO was their issue? ::shrug::

“Banks like J.P. Morgan Chase were so avid to get WeWork’s IPO business—which would lead to a windfall in fees—that they were willing to lend both WeWork and Neumann absurd amounts of money, spurring on the company’s absurd behavior. The board, the people whose responsibility it should have been to rein the company in, was more focused on getting a gigantic injection of cash from Softbank that would have allowed its members to cash out their shares at a huge profit; when that failed, they pushed for an IPO to get themselves the same.”

How, and I can’t stress this enough, the FUCK is any of that allowed to remain legal?

Because the people who benefit from it are also the people who make the laws.

It is a truism that venture capitalism is “doing things before they become illegal”

Neumann’s background is also an interesting part of this story: he was raised on a Kibbutz for a little while and couldn’t keep from bringing it up. This may be why selling WeWork as some sort of money-printing commune came so easily to him and why people loved the idea so much. If you’re selling to wealthy, fortunate, but disconnected one-percenters, why not make “real togetherness” your unique selling proposition? That’s some cult-level stuff, right there.

It also makes Neumann creepily similar to the villain in Tom Rachmann’s excellent “The Rise + Fall of Great Powers,” which seems to more or less foretell him, if I’ve got my dates right. If there’s anything worse than a committed autocrat, it’s a hippie gone mad with power.

But the real meat of The Cult Of We, and what sets it apart from previous recitations of this story, is the skill and clarity with which Brown and Farrell describe the economic and financial environment that made WeWork’s absurd peak valuation of $47 billion possible in the first place.One key aspect of the WeWork story that I don’t think gets enough attention is this sort of thing is a direct consequence of the world-wide concentration of wealth. When you’re a billionaire in China (or Dubai or London or San Francisco), there’s literally not enough things to do with your money, so you end up throwing some of it at wild ideas like this because why not, even if you lose every penny you’ll still be stupid rich. This also, by the way, is why the real estate market in very expensive cities like Seattle, the Bay Area, and Vancouver B.C. features high-rise condominiums with upwards of a 60% vacancy rate – those empty units are owned by someone who will never live there, but buying real estate on the other side of the world is better than just letting your money sit in the bank until the Communist Party maybe decides to seize it.

I believe they have the new mega high rise condos along Park Ave in Manhattan at a 75% vacancy rate.

I actually worked in a WeWork facility for about six months, in late 2016. I called it the “glass-walled nightmare,” although I did eventually figure out how to navigate the place after a while. I did appreciate the unlimited free coffee and beer in the lobby but even then it seemed like a weird extravagance.

I was in a Staples today and realized they have a little “co-working” area in the back, which I later looked up and is called “Staples Studio”.

Huh, I hadn’t heard about that, but I’m not surprised. There’s probably a ton of coworking (cow-orking) facilities I’ve never heard of, not to mention existing companies I have heard of expanding into the space. (A quick search indicates that the Staples Studio locations are all in Massachusetts or Canada.)

There’s so much wrong with startup culture, and even well meaning startup owners don’t always understand how their investors’ incentives don’t line up with their own. I knew someone in Silicon Valley who was buying crazy expensive office chairs for his employees and throwing a lavish Christmas party, and when I questioned the expense he said the VCs said some conspicuous spending would make them look successful, and thus like a good investment to others. He didn’t seem to understand that that’s not advice you’d get from someone who also wants to build something long-lasting. The VCs were advising him that way because they wanted to sell their stakes, and they wanted to make a profit.

Was the Hulu doc that bad? I was kind of eyeing but I guess I’ll give it a pass.

No. It was a very good film. Check it out.

“Most importantly, maybe, he’s tall. (All books about start-ups, including this one, love mentioning how tall people are.)”There are studies out there that show that people tend to associate tall men with competence and authority. Males over 6ft2 are far more prevalent amongst CEOs than the general population. Says nothing about competence but here we are.

General officers in the US army tend to be rather disproportionately tall as well. I met the current SecDef Lloyd Austin once when we we both in the army, and man, that guy is just massive even for a general.

I read once: if you walk into an office and don’t know who the boss is, just look for the tallest, whitest man you can find.

Honestly, I’ve been the mistaken recipient of this. “Hey! Great to see you again! You down here slumming before the meeting?” “Oh, hi, yeah, I’m a temp brought in to handle your failing system architecture. You want the guy who’s about three inches shorter than me and balding, upstairs, fourth door.”

It made for a rather funny and lighthearted episode of Behind the Bastards. https://www.iheart.com/podcast/105-behind-the-bastards-29236323/episode/part-one-the-idiot-who-made-54136534/

I thought the hulu doc was perfectly fine for someone who thought WeWork was some sort of dumbass cult (ME) and explained the nonsense in a manner that was easy to understand for someone (ME) who can’t be bothered to know all the details, but just wanted a rough sketch of what happened. Not everyone needs a detailed deep dive into why some jackass duped a bunch of greedy/naive dummies into their cult of personality. I’m old enough to have seen this kind of thing before.