The Impossible Fortress both celebrates and subverts ’80s nostalgia and rom-com tropes

Aux Features Books

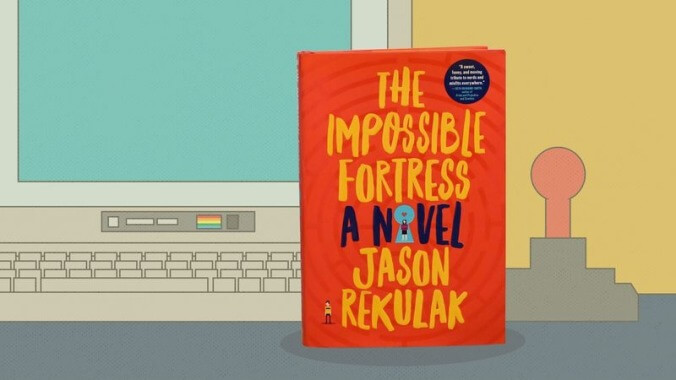

It’s a good thing that The Impossible Fortress is such a fast and easy read, because it would be all too easy to abandon it during the book’s bumpy start. Set in 1987, the first few pages of Jason Rekulak’s debut novel are nearly as laden with nostalgic references as Ernest Cline’s books. Rekulak introduces his ninth-grade misfit protagonists debating whether Freddy Krueger or Rocky Balboa would win in a fight, snacking on pizza bagels, and watching the MTV Top 20 Video Countdown. Fortunately, once the scene is set, the references trail off, revealing a sweet and surprising story about young love.

The Impossible Fortress is set in the small town of Wetbridge, New Jersey where wealth means having two working parents so you can afford new clothes but fortune means having a single mom who works nights so you’re free to hang out unsupervised. Narrator Billy Marvin is that fortunate kid, flunking school as he neglects studying to hang out with his two best friends and practice his computer programming. When the pervy trio, who have curated the PG-13 section at the local video store to optimize for female nudity, discover that America’s sweetheart Vanna White is in an issue of Playboy, they set out on a quest to get their hands on the magazine. Attempts to get an older person to buy the issue for them or bluff the gruff owner of Zelinsky’s, the one store in town that stocks the magazine, quickly give way into an insane plot to steal it—pushed on the naive trio by a neighborhood cool kid who clearly has his own agenda.

Then Billy meets the storeowner’s daughter, Mary Zelinsky, and discovers a kindred spirit who’s happy to work with him to design a video game they hope will get the attention of their programming hero. Billy’s growing infatuation with the girl who could be the key to their theft leads to a goofy mix of rom-com and heist tropes. As with the reference overload, it could be easy to become discouraged by what appears to be a clichéd story with clear good guys and bad guys. But Rekulak surprises, subverting tropes by adding bits of depth to most of his supporting characters to show that people who’ve taken bad turns sometimes deserve second chances and nice people can make very bad decisions.

Most notably Rekulak uses the traditional “boy loses girl” segment of the story to take a hard and honest look at misogyny and male entitlement with the previously highly sympathetic Billy going on a rejection-fueled rant. “In a flash of clarity I understood all the stories I’d heard about girls—all the movies and TV shows and pop songs—they were all true! Girls lied. They were manipulative and untrustworthy.” He retreats from the real feelings he had for the overweight, smart, and charming Mary by directing his lusts back to the posters around his room, “all my gorgeous and willing supermodels with their slender legs and hairless arms and pouting lips. From now on, I would set my sights on one of them like a normal person… And Mary Zelinsky would die a virgin—unloved, unwanted, untouched.”

Rekulak’s writing style is so visual and his story so neat and contained it practically begs to be adapted into a movie. There are a few highly entertaining illustrations scattered throughout, like the digital supermodel Billy designs that accompanies a debate about whether zeros or asterisks are better for portraying nipples. More delightful is the regularly edited map of the route Billy and his friends will need to take to pull off their heist, updated as they integrate new data like the patrol of the Communist-fearing neighborhood police officer or the need to distract Arnold Schwarzenegger, a yappy shih tzu that lives in building next to Zelinsky’s. There’s even a mixtape of period love songs that’s key to the plot that could provide a soundtrack. The ability to turn the time setting references into visual cues rather than name-dropping would also improve Rekulak’s narrative. But until then you can just enjoy the breezy prose and charming story. And if the video game Mary and Billy program together during their budding friendship intrigues you, there’s a playable version on the author’s website and code for how it would have been made for a 1987 computer at the opening of each of the book’s chapters.

Purchase The Impossible Fortress here, which helps support The A.V. Club.