The first biography of Fred Rogers is touching, but treats its subject with kid gloves

Aux Features Book Review

It’s lucky for society that Fred Rogers is having a moment in 2018, some 15 years after his death and 50 years after the premiere of Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood. June saw the release of Won’t You Be My Neighbor?, an acclaimed documentary about the television host and all-around paragon of human decency, while Tom Hanks will be donning the cardigan and sneakers in an upcoming biopic. In an age of dispiriting coarseness and unrelenting anger, from online trolls all the way up to the man in the White House, Rogers’ warmth, patience, and message of love for all feel almost like radical acts.

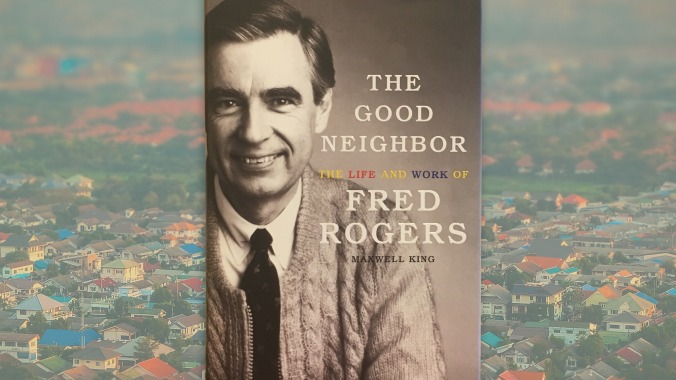

Arriving in between those cinematic treatments is The Good Neighbor, a biography by Maxwell King that stands as literature’s first full-length consideration of Rogers’ life and work. As such, it’s almost certain to be the most exhaustive of the projects when it comes to telling the story of its subject’s life and exploring what made him tick. But at the same time, the book’s extra details don’t shed a ton of new light on things. If you’ve seen the movie, the things you’ll learn from the book are essentially trivia.

The comparison between the biography and the documentary is not a flattering one, and to be sure, some of this is an unfair fight. Because so much of Rogers’ power came from how he presented himself, and because there’s a wealth of archival footage to draw on, there’s obviously an advantage in how the film can actually put him on screen. Not to belabor the obvious, but it’s one thing to read about Rogers’ Senate testimony in 1969, when he appealed to our elected representatives’ better nature in asking for funds to be allocated to PBS. It’s quite another to actually watch it.

But even with an apples-to-apples comparison—on issues they both face, like structure, pacing, and point of view—the book can’t help but feel a bit flat and perfunctory. In the most egregious example of this, the book’s introduction discusses the famous moment between Rogers and Jeff Erlanger, a child with quadriplegia with whom he shared a special connection. When King discusses the encounter later in the book proper, there are literally several paragraphs that appear again word for word, apparently cut and pasted in.

That by itself speaks to a bizarre kind of corner cutting (calling it laziness feels like a stretch since King’s reporting is pretty comprehensive; the author was once the editor of The Philadelphia Inquirer), but even setting this oddity aside, the event is poorly presented from a storytelling point of view. After describing Rogers and Erlanger’s on-air discussion, King immediately jumps ahead to reveal that Erlanger would eventually give a speech inducting Rogers into the TV Hall Of Fame. Had he saved that reveal for the end of the book, it would’ve had a moment of climatic or valedictory power that’s otherwise missing. King presents a great number of facts in the book, but does little to finesse them into real storytelling.

Part of the issue may be that the author is just too close to his subject to be objective from either a critical or artistic perspective. King previously served as the director of the Fred Rogers Center For Early Learning And Children’s Media, and was a senior fellow there during the writing of the book. The proximity undoubtedly gave him insight and access, but the book is missing a certain amount of distance or skepticism. There’s a moment when Rogers, in an on-air cooking demonstration, makes so much popcorn that it bubbles out over the pot. He demands a reshoot, concerned that “the uncontrolled popping and spilling could be frightening” for little ones. Was Rogers being overly sensitive? Did he miss a chance to teach a lesson? Sometimes it feels like Rogers used “think of the children” as a shield for being controlling and demanding, but King skips over probing these events, not giving enough information to confirm or dismantle such musings.

One of the real strengths of The Good Neighbor is that it doubles as not just a history of early TV production, but also a primer on early-childhood education theory. There’s an interesting subplot about the friendly nonrivalry between Neighborhood and Sesame Street—which focused on cognitive rather than social or emotional learning, and which got relatively loud and zany compared with Neighborhood’s meditative pace—but it lacks anything conclusive about the strengths and limitations of either approach. This is something that a book, compared with the documentary, could easily get into; that it doesn’t is a bit of a missed opportunity.

Of course, if King is reluctant or unable to write a negative word about his subject or his work, doesn’t that just come with the territory, given the subject? Ultimately The Good Neighbor gets the job done, but it’s hard to forget that others have done this same job better.