Theodor Seuss Geisel, or Dr. Seuss as he was best known, published 60-plus children’s books in his lifetime—the publication of posthumous titles show no stopping. And nearly all adhere to the same basic plot: the protagonist encounters a new world (a new street, new zoo, new alphabet, an egg or pair of siblings to babysit) and chaos ensues (strange creatures! letters! and words!) set to rhyme. It’s an apt metaphor for adolescence, an age accented by the topsy-turvy, too-muchness of the world.

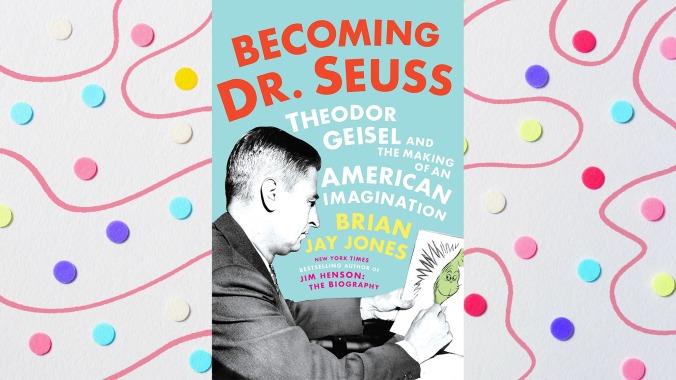

But contrary to the worlds he created, Geisel’s life was rather un-Seussian. He wrote with steadfast discipline, quietly traveled the world between books, filled ashtrays with the spent cigarettes that would kill him at the age of 87. Geisel quashed any entreaties to pen his memoirs, bemoaning that they “would become a source of irritation to the reader in a 200-page volume,” before grinchily groaning, “Who could possibly care about all these details?” Brian Jay Jones, that’s who. Jones, the author of lauded biographies of Jim Henson and George Lucas, takes up Geisel’s challenge, filling 400-plus pages with more details than McElligot’s pool has fish.

Becoming Dr. Seuss begins where else but Springfield, Massachusetts’s Mulberry Street, the setting for his first kids book, a series of “outlandish tales” in which young Marco turns “minnows into whales.” He wrote and illustrated for the college humor magazine at his beloved Dartmouth College, where Geisel’s classmates voted him Class Wit and Least Likely To Succeed. He moved to Oxford, England in hopes of earning a PhD in literature, and met a girl with a most Seussian “lopsided smile” who encouraged him to quit the classroom for cartooning back home. Like Warhol after him, Geisel first succeeded in commercial advertising, drawing punny toons for Flit insecticide, Esso motor oil, and Schaefer beer, among other corporations. Many of these ads would foretell the menagerie to follow: human-eyed fish, bizarro birds, all-knowing elephants, elaborately whiskered humans, and vaguely feline creatures.

After releasing four books to lackluster sales, Geisel struck gold in 1940 with Horton Hatches The Egg, the story of an ever-faithful elephant who braves storms, ridicule, hunters, and the circus to hatch the titular ovoid. Though Geisel would repeatedly claim that most of his book carried no moral message— “What’s wrong with kids having fun reading without being preached at?” he bellyached—reviews praised Horton’s stick-to-itiveness, an allegory ripe for the anti-appeasers of the early Second World War era.

During the war, Geisel couldn’t help but showcase his progressive leanings in an upturned world. He churned out hundreds of political cartoons for the leftist PM newspaper, and in 1943 joined the Army’s Signal Corps. Under the leadership of lieutenant colonel Frank Capra, one of Hollywood’s most successful directors, Geisel helped write propaganda documentaries and the Private Snafu series of cartoon shorts, which collected an all-star lineup of talents, including animation wizards Chuck Jones, Friz Freleng, Mel Blanc, and Ray Harryhausen.

Beginning in 1950, Geisel assembled arguably one of the most fecund and financially successful decades in the history of artistic expression, a period bookended by Yertle The Turtle And Other Stories—in which the authoritarian Yertle is a stand-in for Hitler—and Green Eggs And Ham—Seuss’ bestselling book, at over eight million copies sold. In 1957, Geisel unleashed two of literature’s most enduring characters in The Cat In The Hat and How The Grinch Stole Christmas! America had become Seussville.

But Geisel’s life wasn’t all Shmoopity-Shmoop, if you know your Lorax lingo. Half hagiography, Jones’ book is unafraid to recount the Schloppity-Schlopp that marred Geisel’s long career: The racist and misogynist cartoons penned during his early years. His dictatorial behavior while co-running the Beginner Books imprint. The absence of female protagonists in his books. And, most heartbreakingly, the suicide of his saintly wife, Helen, who swallowed a half-bottle of barbiturates in 1967, at the age of 69, after learning of Geisel’s affair with a woman whom he would marry the following year.

Beyond that, you won’t find much drama in these pages. Nor will you find deeper interpretations of Geisel’s work, or an analysis on how the past three decades, following his death in 1991, have treated his reputation and oeuvre. In the end, Becoming Dr. Seuss feels both like too much and too little. Still, Jones manages to craft a loving portrait of a singularly imaginative life, a life that seemed simultaneously big and small. How you’ll feel about Jones’ own penchant for too-muchness will depend on your post-adolescent adoration for Dr. Seuss. Would you still read him on a boat? With a goat? In the rain? On a train? In Korea? You get the idea.

18 Comments

I do not like hagiography. I will not read them in a loft. I will not sit them near Robert Frost. I will not read them in a kindle. I will not take them in a bindle. I will not quote them on instagram. I will not enjoy them with locally sourced green-eggs-and-ham!!

Horton Emits an Ugh

Horton emits…

During the war, Geisel couldn’t help but showcase his progressive leanings in an upturned world. Pictured: “progressive leanings,” totally not super-racist Japanese stereotypes.

And at the same time he was drawing cartoons slamming factory owners for refusing to hire African-American workers.

People are weirdly complicated.That middle one, for my money, is the worst of the bunch.

I dunno buddy, I think those look more like the also-mentioned-in-this-article “racist and misogynist cartoons penned during his early years.”

What “progressivism” means changes with the times.

Sure, progressivism changes with the times, but I don’t think it ever included abject racism.

Are you completely unfamiliar with the original Progressive movement? Many of them were rather explicit that the labor legislation they were pushing would reserve jobs for able-bodied white men, which they believed would have eugenic benefits. Woodrow Wilson was a noted Progressive who also segregated D.C. New Orleans was something of an outlier in the south as a former French colony which didn’t follow the “one-drop rule”, which led to it being regarded as backward by the forces of Jim Crow, who called themselves “progressive” in bringing it into line with the rest of the south. You can read “Illiberal Reformers” for more on that.

Capital P “Progressive” as in the Progressive Era from the 1890s to the 1920s seems like a different thing than the adjective “progressive” leanings of a cartoonist in the 1940s.Confusing the two is like equating democratic norms with the Democratic Party, which, you know, is a thing that occasionally happens:When a delegate asked unanimous consent to change a platform amendment to read the “Democrat Party” instead of “Democratic Party,” Mr. Kemp objected, saying that would be “an insult to our Democratic friends.” The committee later decided to drop the issue because it lacked unanimous support.The term “Democrat Party” has been used in recent years by some right-wing Republicans on the ground that the term used by Democrats implies that they are the only true adherents of democracy.Democrats in the House objected so loudly to the terminology several years ago that the House Republican leadership, including Mr. Kemp, openly called on Republicans to say “Democratic” to avoid needless rancor between the two parties.

a) not sure why you are pretending the review didn’t mention the racist cartoons…but thanks for posting

b) if you look at the rest of his stuff you’ll see it was progressive overall…for a white guy in the 1940s.

c) democratic/democrat is ironic, given that a lot of right wingers are arguing America isn’t a democracy at all, but only a republic, which is just another excuse for elitism and disenfranchisement

a) The review posits that as just “his early years” when it’s clear that it carried significantly past that. b) Fuuuuuuuuuuuuck that. Racism is always bad, and I’m not going to make excuses because I like how he rhymed “cat” and “hat.”c) Yeah, that was the point I was making.

those were his early years, he was active a long time!You should get a copy of “Dr. Seuss Goes to War,” it has those you posted, but it’s pretty amazing overall. And don’t get me wrong, the “Fifth Column” one is really despicable. However, I guess I fucking hate Russians and think many of them are potential spies and they’re not even trying to wipe me off the face of th…..oh wait they are, never mind…but I wouldn’t draw them racistly, just cornholing bears.

Perhaps capital-P Progressive should be reserved for proper nouns, like the Progressive Party which nominated Teddy Roosevelt as a third party presidential candidate, or the later parties of the same name which nominated Bob La Follette & Henry A. Wallace. I will remind you that the quote I responded to said

Sure, progressivism changes with the times, but I don’t think it ever included abject racism

so the 1890s-1920s would actually be relevant. And it’s not like those old-timey progressives were thought of as never having been deserving of the name. Things like prohibition, which had been endorsed by Wilson and closely linked in the public’s mind to female suffrage, were rejected by the time FDR was elected. But that didn’t mean rejecting the rest of progressivism. And in the 1940s white supremacists in the south were still considered acceptable partners in a political coalition, and the main political concerns were other matters.One of the other targets of Seuss’ political cartoons was Charles Lindbergh, who attempted to return to his position in the Army Air Force when war broke out and instead wound up a civilian consultant in the Pacific theater (who nevertheless flew in combat missions). Relevant to this discussion, he was while an isolationist who had opposed entry into the war also an avowed racialist who believed in the “yellow peril”. His diaries at the time included entries like these:

“I am shocked at the attitude of our American troops. They have no

respect for death, the courage of an enemy soldier or many of the

ordinary decencies of life. They think nothing whatever of robbing the

body of a dead Jap and call him a “son of a bitch” while they do so.

“I said during a discussion with American officers that regardless of

what the japs did I did not see how we could gain anything or claim that

we represented a civilized state if we killed them by torture.”

Is it that shocking that an ordinary person might express venomous views at one time when inflamed against a threat, but at a later time might regret it? Earl Warren, later famous for judicial decisions striking down segregation, also advocated the internment of the Japanese when he was Attorney General (later to be governor) of California. He wrote decades later that he greatly regretted his actions.On a broader societal level, I think American attitudes toward the indigenous people of this country are interesting. The Declaration of Independence castigates the King of England with (among other charges)

“He has excited domestic insurrections amongst us, and has endeavoured

to bring on the inhabitants of our frontiers, the merciless Indian

Savages whose known rule of warfare, is an undistinguished destruction

of all ages, sexes and conditions.As they were not regarded as following civilized rules of warfare, they were thus fair game for frankly genocidal policies (which later helped inspire Hitler). Even Mark Twain, who had Huck Finn choose eternal damnation over betraying his friend back to slavery, relied on fear of Indians to create the villain in Tom Sawyer. Over time as more and more were defeated and confined to reservations, there was space for attitudes to begin to change. The man who coined the term “racism”, Brigadier General Richard Henry Spratt, was actually in charge of a boarding school for natives, with the motto “kill the Indian… and save the man” (a model he advocated extending to other ethnic & religious minorities). Today this would be regarded as abhorrent cultural genocide, yet another example of how standards have changed over time.

Just a slight correction – Frank Capra didn’t later become one of Hollywood’s most successful directors, he already was one of Hollywood’s most successful directors. His name was above the title of his movies and he’d already won multiple Academy Awards by 1941. He actually signed up for service at the very peak of his career. It’s kind of remarkable, which is why I felt I should point it out.

You’re absolutely right. Thank you.

Wow. Absolutely no mention of the racist imagery running through his work? No thanks.

This sounds like if I read it the only new things I’ll learn are bad stuff that might make me enjoy his books less, which seems like a losing proposition.