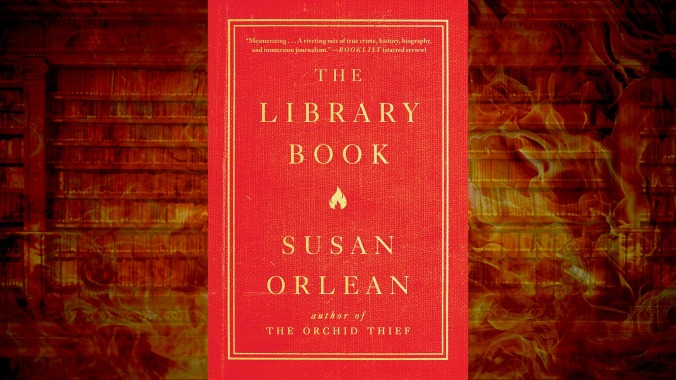

A historic fire illuminates an enduring institution in Susan Orlean’s The Library Book

Aux Features Book Review

Early in The Library Book, Susan Orlean describes the joy of scanning a library’s shelves and discovering the dramatically different subjects that have somehow become neighbors. “On a library bookshelf, thought progresses in a way that is logical but also dumbfounding, mysterious, irresistible,” she writes.

That’s also an excellent description of Orlean’s own thought process as she writes her sprawling works of nonfiction. Her latest, The Library Book, is ostensibly about a fire that destroyed much of Los Angeles’ Central Library in 1986, the same way her bestselling book The Orchid Thief is about a flower poacher. The New Yorker staff writer has found a formula that works: She starts with a singular character or event and then lets her research take her where it will, delivering a series of fascinating anecdotes rather than a cultivated, coherent whole.

In The Library Book, that winding process leads to an exploration of the creation and evolution of Los Angeles’ library system and its crown jewel, Central Library. It’s a story filled with quirky characters and glimpses of bigger movements like city librarian Charles Fletcher Lummis, who traveled from Ohio to Los Angeles on foot in 1884 and wound up in a fight with the current city librarian, who didn’t appreciate being fired just because the library board believed a man should run things. The library is used as a lens to track Los Angeles’ growth; the impacts of the Great Depression, Prohibition, and World War II; questions about the importance of historical preservation; and libraries’ ever-changing role in society.

Orlean spent years interviewing and researching for the book, and she introduces people she spoke with through a series of small portraits that provide a glimpse of what it’s like to work in a major library today. There’s a reason why a Forbes editorial suggesting that Amazon replace all libraries with stores was lampooned until it was taken down. Libraries have always been more than a repository for books, and The Library Book includes accounts of how the spaces have been used for everything from teaching immigrants English to educating teens about consent. One issue confronted throughout is how libraries have become a resource for homeless people, and how they maintain inclusivity while preventing violence, drug use, drinking, and public sex. “Every problem that society has, the library has, too, because the boundary between society and the library is porous; nothing good is kept out of the library, and nothing bad,” Orlean writes.

Orlean has a tendency to place herself in the narrative, and it’s a bit uncomfortable when she’s talking about the library’s homeless patrons or a day she spent signing them up for its outreach program. She writes that she was nervous about helping because of their air of “menacing unpredictability” and how surprised she was to find a man who looked “as immaculate as a dentist” looking for food. Even worse is the self-indulgent segment where she writes about wanting to burn a book to experience a bit of Central Library’s historic fire. She agonizes about what to set ablaze before choosing a copy of Fahrenheit 451, Ray Bradbury’s dystopian novel in which books are outlawed and firemen are tasked with burning them. But such missteps recede when she talks about how personal the subject is to her. The Library Book served as a way for Orlean to honor and mourn her mother by reminiscing about the trips to the library they took together, reinforcing those memories even as her mother lost them to dementia.

The biggest weakness in The Library Book may be the focus on the Central Library fire. Orlean opens the book almost identically to the way she started The Orchid Thief—by describing the man behind the crime at the center of her narrative. But while John Laroche—later magnificently played by Chris Cooper in Adaptation—was brazenly guilty and a fascinating character who Orlean could get to know personally, the fire’s prime arson suspect, Harry Peak, died decades before she started her research. The chapters dedicated to him fall flat, Peak coming across as merely sad, a pathological liar and failed actor who may not have actually committed the crime he became infamous for. While the information on the efforts that went into restoring the library and the emotional impact the disaster had on the people that frequented it provides some fascinating material, Orlean is never able to make the search for the fire’s cause feel nearly as dramatic.

Luckily part of the charm of a library, or an Orlean book, is that one might come looking for one thing and find something very different yet still enjoyable. In the end, The Library Book isn’t really a story about a library that was destroyed so much as a treatise on why libraries endure.