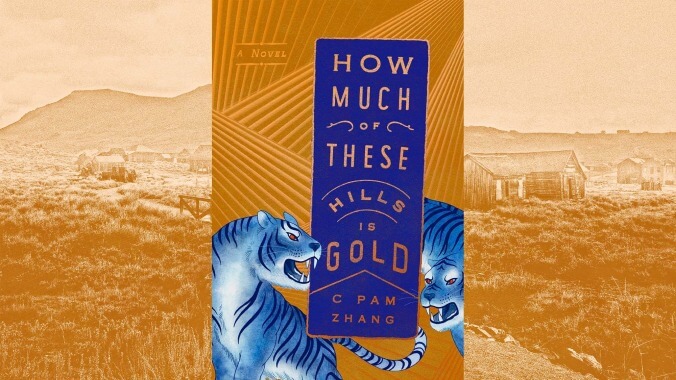

How Much Of These Hills Is Gold mines an epic Western from an immigrant story

Aux Features Book Review

In the opening pages of C Pam Zhang’s debut novel, How Much Of These Hills Is Gold, preteen siblings Lucy and Sam become orphans. Their abusive father, Ba, “dies in the night, prompting them to seek two silver dollars” to complete a funeral ritual. Penniless, they wander the valleys of the American West for weeks with their father’s decomposing corpse. Tiger paw prints and the bones of 18-foot-tall buffaloes dot the vast, empty wilderness. Stopping at a bank, Lucy tries to bargain with, then Sam shoots and misses, the teller, who says to Sam, “Run on, you filthy. Little. Chink.”

The two, it’s revealed here, are first-generation Chinese immigrants. Rather than venturing west, like the opportunists of America, the family had crossed into California eastward from China to prospect for gold—just as 25,000 other Chinese people did between 1849 and 1851.

Despite this, Zhang doesn’t say the word “China” even once in her novel, set just after the height of the Gold Rush. She instead references the exoticization and violence that Lucy and Sam face as a result of their ethnicity. Ma, their mother who died of mysterious circumstances three years prior, speaks in untranslated Chinese and yearns for home, “a place of cobbled streets and low red walls, mists and rocky gardens.” To her children, she speaks of their past “in a jumble of myth.” “There’s no one like us here,” she mourns.

Lucy, meek and desirous of cultural status, and Sam, a wannabe outlaw who was Ba’s clear favorite, attract and repel each other as they deal with the unspoken trauma of their parents’ death and chase variations of the elusive American Dream. Displaced and alienated from a country that does not recognize them as its own, neither has known anything resembling a home.

The distance the two siblings in How Much Of These Hills Is Gold travel is undefined, and there’s no way of knowing, as few locational and cultural references exist in the novel. Yet the setting sprawls, alternating between wonder and fear of the unknown in crackling, atmospheric prose. To Lucy, the primary narrator, “the hills roll by with a speed that makes them liquid.” In a moment of vulnerability, she flees from Sam, “the grass so parched it draws blood, hatching her legs with a delicate pattern.”

Despite some characteristics endemic to Wild West narratives (buzzards circling prey, saloons filled with seedy strangers), the world of How Much Of These Hills Is Gold feels wholly original, and Zhang imbues its wide expanse with magical realism. According to local lore, tigers lurk in the shadows, despite having died out “decades ago” with the buffalo. There also exists a profound sense of loss for an exploited land, “stripped of its gold, its rivers, its buffalo, its Indians, its tigers, its jackals, its birds and its green and its living.”

The story toggles back and forth in time—from Lucy and Sam’s childhood, when their parents strove for normalcy, to five years into the future, when the siblings reunite after a period of estrangement, nearly unrecognizable to each other. Featuring a love triangle and a foray into the class of newly moneyed prospectors, the fourth and final section feels like an entirely different novel. In the last 30 or so pages, much of the momentum is lost, with characters acting from motivations that don’t comport with what we’ve come to understand about them. The ending is also punishing in a way that feels less poetic than ham-fisted—like a story loop in HBO’s Westworld that’s bound to end in tragedy for the character, despite best intentions.

Notwithstanding the disappointing conclusion, How Much Of These Hills Is Gold is a thrilling and epic debut that elides stereotypes associated with Chinese or Western narratives and which forges its own mythology. Lucy and Sam’s world in the wilderness feels entirely lived in and fully imagined, and reflections on home, gender and sexual identity, and familial duty parallel strong stylistic choices that, even if the ending doesn’t, do genuinely pay off.