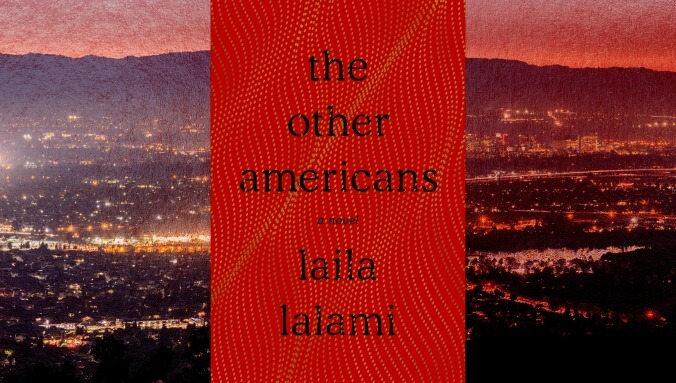

The personal is political, and vice versa, in Laila Lalami’s engrossing The Other Americans

Aux Features Book Review

“When we moved to America thirty-five years ago, many things took me by surprise… above all, I was surprised by the talk shows, the way Americans loved to confess on television.” This impression comes from Maryam, a Moroccan immigrant and one of many characters that populate Laila Lalami’s fourth novel, The Other Americans. Maryam pines for the homeland she left behind and is often bewildered by the social mores of her adopted country. In addition to providing insight into who Maryam is, this thought reveals a bit of narrative self-awareness, for The Other Americans reads like a multi-voice confessional that wouldn’t be out of place in one of the talk shows Maryam loves to watch—if those talk shows also exhibited Lalami’s sharp storytelling skills and precise language, of course.

The catalyst for Lalami’s story is the hit-and-run death of Driss Guerraoui, a Moroccan immigrant living in small town America. Although her three previous works have all centered around Moroccan immigrants and that country’s political strife, this is the first that Lalami has set in modern-day America. Despite the change in setting, many of her thematic concerns remain the same: immigration and exile, deep political division, and the meaning of home.

In this case, the Mojave Desert serves as the backdrop to explore these issues. As Lalami delves into the details surrounding Driss’ untimely death, we hear from no fewer than nine characters who have connections to him. Each chapter shifts from one narrator to the next, seamlessly weaving a complete portrait of the events surrounding that night. It’s one of the main draws of the novel: Each voice is so robust and distinct that there’s no risk in getting lost in the crowd. We hear from the aforementioned Maryam, the victim’s widow; as well as the police officer investigating the case; a neighbor with a possible vendetta; and one key eyewitness. We hear most from Nora, who becomes fixated on finding justice for her adored father, and Jeremy, an Iraq war veteran and Nora’s childhood friend. The bulk of the plot revolves around Nora trying to find out the real motives behind her father’s death and Jeremy attempting to come to terms with his troubled past.

The whodunit element of the novel is interesting enough, but it is evident from the get-go that this isn’t the mystery Lalami cares to explore. Even superficial fans of murder mysteries will easily guess the identity of the driver somewhere along the way. What’s more riveting are the secrets behind each narrator. As each picks up the thread of the story, they reveal delicious morsels about themselves that prove to be more gasp-worthy than any clue regarding the killer. These revelations tackle and complicate issues regarding the pursuit and failure of the American dream, the immigrant narrative of success and assimilation, the questionable privilege of racial passing and its resulting erasure, and more, pointing out that the real enigma is the idea of what being an American even means. The book argues that no condition may be more American than that of alienation.

Lalami treats each character as if they were nations unto themselves, and their relationships are fraught with conflict and tension. The Guerraouis’ marriage is described as a “Cold War”; the constant arguments between Maryam and Nora are “battles [that] never ended in a clear victory.” She isn’t the only one to see war as the “father of all things, the king of all things.” Efraín, the eyewitness afraid to come forward because he is undocumented, frets about the peace that has been robbed of him and thinks of Guerraoui as “Guerrero,” or “warrior,” in Spanish. “Merciless in his campaign against me,” Efraín thinks bitterly, as news of the hit-and-run continues to haunt him. Other characters see themselves as either the occupiers or the occupied, feeling invaded or ambushed, proclaiming themselves defenders, wearing clothes like armory, or halting conversations as a way to surrender.

It’s not particularly original to evoke martial vocabulary when describing the private lives of others, but it’s often used in a vacuum, as if these domestic clashes were deprived of any social or historical context. Lalami refuses to do that. Her novel hammers home not only the idea that the personal is political, but also that the political is personal. State-sponsored violence in Morocco, post-9/11 Islamophobia, the U.S. intervention in Iraq, the war on drugs, America’s history of racial discrimination—these all forge, in one way or another, the Other Americans’ characters. They are also some of the major obstacles that prevent them from fully relating to one another, as the past harms that each of these conflicts has inscribed on them bubble up in their intimate moments, threatening any sustained alliance with their loved ones.

Although Lalami commands the attention of her readers with her expert pace and acute insights, she makes a few missteps. Efraín ends up being nothing more than a plot device, left to drift off and disappear from view in the book’s second half. It’s a disappointing resolution for a character who warrants our emotional investment. A few dream sequences feel like amateur gestures for a writer who usually soars above such platitudes. And there were moments of what can only be described as forced political psychoanalysis, where the line between a character’s social and ethnic identity and their personal motives was made so explicit that readers might be turned off by the sermonizing undertones.

Ultimately, the novel is engrossing. Its structure so mirrors the quiet power of oral histories that one wonders who these characters are addressing. The answer may be other Americans. For a book that is fully aware of the extent that the United States can disappoint the people who live here, it doesn’t come off as grim, perhaps because it offers a pathway out of estrangement. The novel finds hope in stories—sharing them, receiving them, and creating them. After all, it is only through the multitude of perspectives that the reader can create a cohesive picture surrounding the death of Driss Gerreaoui. It is also how the characters find meaning in their own personal histories, begin to establish intimacy with one another, and build a space that may allow them to heal. It’s what makes people feel less “other” and a little more united.